Against lists of books

We've all got such good taste

Once you’re done being US President, I think they should kill you. You get four or eight years to kill anyone you want, destroy entire countries at will, throw around billions of dollars at whatever cretinous idea catches your fancy—but once it’s all done, once the White House dog’s being carried away by helicopter and the next guy is giving his inauguration speech, the Secret Service should ferry you down to a cosy underground bunker, a nice little room, a kind of Presidential man-cave, decorated with pictures of you golfing, shaking hands at a G7 summit, meeting the Pope. A few old campaign posters. Remember what it felt like to win? That rush? The Secret Service guys bring you a hamburger and a cool, refreshing glass of Coke, and once you’ve eaten your limbs start feeling heavier. There’s a sofa; maybe you should just lie down. You did well, didn’t you? You made it: the most important person in the world. Don’t you deserve a rest? Afterwards, they’ll build a modest statue of you overlooking the National Mall, with your ashes inside, and small creeping vines, which know nothing about politics, for whom every human is just a lump of nutrients, will climb slowly up your feet.

This would vastly improve American political discourse. Their candidates would be different; stranger. Fewer billionaires, fewer dynasts, fewer used-car salesman types with Vaseline grins, fewer mediocrities constantly falling upwards, fewer delusional maniacs who expect us to believe they’re only running to give hope to some imaginary little girl. Instead, you’d get weird, intense types, eyes bulging several inches out their skulls, willing to sacrifice their lives for a deranged private cause. Mangy extremists with nothing left to lose. (Maybe all the unsuccessful candidates should be executed too, just to be safe.) There is, of course, the chance that one of these psychos might decide to push the big red button on his last day in office, take the rest of us down with him. But I think it’s still worth the risk. Because under this system, at least we’d never have to see another of Barack Obama’s summer reading lists again.

The weirdest thing people believe about Barack Obama is that he gets some 24-year-old intern to come up with his summer playlists and reading lists. There’s no way a man in his sixties could possibly have heard of the most popular music in the world! If you think this, you understand nothing about Obama, or the world. Of course he listens to Charli XCX and Billie Eilish and Megan Thee Stallion. Of course he compiles those lists himself. Maybe on a sunny afternoon in Martha’s Vineyard, on the patio with his iPad and a cup of coffee. What else do you think he’s doing? It’s his job to have good taste; it’s the only job he’s had for the last twenty years.

At first, I thought my main objection to Obama’s summer reading list was that I didn’t like the books he chose. They all belong to a very precise genre. Call it Obamalit. The sort of novels that have titles like All The Little Things We Weren’t or My Year Of Golden Days And Silver Dusks. Graceful cover designs, swirling pastel blobs, maybe resolving into a stylised image of a woman’s face. A sticker informing you that this book was shortlisted for a prize named after a supermarket chain. The prose is always polished and neutral, made up of short clean declarative sentences, and it’s about growing up in an immigrant family or the breakdown of a relationship examined from multiple perspectives. Meanwhile, the nonfiction is titled The Democracy Fix: Why Our Institutions Are In Peril And How Reading This Book Can Save Them, and it’s usually written by someone whose second house was bought for them by—once you drill through all the think tanks and charitable endowments—the Saudi royal family. The world churns out these books, people somehow buy them, and afterwards Barack Obama comes along to give them his imprimatur, so you know you’ve made the right choice.

Does Obama have any actual interests? He has, it’s true, recommended a few books about basketball. But before he commanded a fleet of armed drones, Barack Obama was also a senior lecturer in constitutional law. You have to imagine that he’s read a lot of very heavy, serious books on juridical philosophy, and occasionally asked his students to read them too. None of those make the cut. In fact, Obama hardly seems to recommend anything that wasn’t written in the last couple of years. (The sole post-presidential exceptions are VS Naipaul’s A House for Mr Biswas, which got the stamp of approval in 2018, and the novels of Toni Morrison, which were unearthed the following summer.) He never encourages you to read anything that might be hard. Obamalit sometimes deals with serious issues, but the prose is all light and insubstantial. You glide right through it. Like biting into butter. Every actually interesting book out there is, in some nebulous way, unobamable. You can imagine him endorsing a book by an Atlantic columnist about how the breakdown of community has left everyone isolated, sexless, and depressed. But he would never tell you to read something by, say, Michel Houellebecq, even though all his novels deal with the exact same theme. The novels are too grubby, too shot through with bitterness and lust. There’s too much of a singular voice there, and none of it is aspirational.

But I don’t hate everything Obama’s ever recommended. I like VS Naipaul. I like Zadie Smith. This year he told you to read John Ganz, and while I might not always agree with him I think you should read John Ganz too. There’s something creepy about the whole project, though, and it would still be creepy if Obama was telling you to read Annihilation. It is insane to briefly drench the world in blood and then follow it up by becoming a minor middlebrow tastemaker. After the end of his presidency, George W Bush took up painting. Eerie self-portraits: his legs in the bath, a fragment of his blank face in a mirror. Here is a person who achieved the summit of power, and all he did when he got there was kill, maim, and destroy. Now, he’s trying to find out what kind of a man he really is, once all the power’s been stripped away. It might be withered, but he still has a soul. After the end of his presidency, Barack Obama started a podcast sponsored by the Dollar Shave Club. He moved seamlessly from keeping a kill list to regurgitating the bestseller list. Maybe those things are the same. Maybe that’s all he ever was: not a living person, just a symbol of his voters’ good, respectable middlebrow taste.

It’s not just Obama, though. I’m starting to find the whole business of making lists of books disgusting, no matter what the books are and no matter who makes the list. Any list of books is ultimately a way of describing a certain kind of ideal person; it’s a way of telling other people how they ought to perceive you. Accessorising. Ugly behaviour. Case in point: earlier this year, the New York Times produced a list of the 100 best books of the 21st century, with the fantastic innovation that you can check off all the books you’ve read, and afterwards you get a fun shareable image to show off to your friends. Look, here’s mine:

The point isn’t to read these books; the point is to have read them. Actually dragging your wet eyeballs over all that scratchy paper is just an awkward chore you have to go through, so afterwards you can ask people at parties if they’ve read The Line of Beauty, and then, before they’ve even had a chance to respond, tell them that you’ve read The Line of Beauty. You’ve read Cloud Atlas. You’ve read Outline. Yes, you would like a medal, thank you very much. You grew up reading books to earn stickers, and now every time you finish one you start looking around for your reward. But of course some of you are bigger and better and more literate than that. So you get to progress on to the second level of the game, where instead of pointing out all the books on the list you’ve read, you point out all the books you’ve read that didn’t make the list, and complain that they should have, because you’ve read them. The list needs to be a more accurate reflection of you.

The great dispute began the day the list was published, and as far as I can tell it’s still going. Why isn’t there any poetry? Why isn’t there any genre fiction? Why’s it so white? With those preliminaries out of the way, you can get really stuck in. Elena Ferrante doesn’t just take the top spot, she appears three times; meanwhile, Karl Ove Knausgård is absolutely nowhere to be seen. Are you really saying Detransition, Baby or a novel about video game developers is a more significant achievement than My Struggle? And how come Philip Roth’s The Human Stain, one of his late masterpieces, languishes at number 91, while The Overstory makes it into the top 25? Make it make sense. Explain to me what some bog-standard biography of Frederick Douglass is doing in there, in a space that could have gone to Maggie O’Farrell. Where’s Jenny Offill? Where’s Olga Tokarczuk? Where’s Jhumpa Lahiri? Where’s Ottessa Moshfegh? And, given what we now know, how dare they still have Alice Munro?

Since I’ve personally only read sixteen of the New York Times’ 100 best books of the 21st century, I can’t really comment on these complaints. Was the list accurate? Probably not, if only because we’re less than a quarter of the way through the century in question, and unless something really bad happens there are a lot of great 21st century books that haven’t been written yet. The actual best book of the century is called L哈হা哈হাL; it’s written in a pidgin that doesn’t currently exist, and it’ll be published in 2089. Until then, you’ll have to make do with My Brilliant Friend. It’s one of my sixteen; I didn’t hate it. I’d still definitely trade it—along with pretty much every other book on that list—for JG Ballard’s Super-Cannes, but it’s also very obvious to me that Super-Cannes would be a deeply inappropriate choice for the top spot. A lot of writers on the list are busy rubbing away at the familiar slit between the personal and the political, but even though none of them will ever be as influential or as significant as Mark Fisher, he plainly doesn’t belong on there either. The lists he belongs in are all Google docs in twelve-point Calibri, circulated between arthoes and shutins on manky subreddits. Reading his books is part of an entirely different genre of self-performance. You couldn’t Instagram them on a sun-dappled café table with matching nails and an Aperol spritz.

I don’t have the same preferences as the panel that gave us this list. But the idea that this is a problem, that it should better reflect my taste, seems very bizarre to me: if it did, then it wouldn’t really be my taste any more, and why would I want that? Clearly I’m not the target audience, though. In the general literary world the list was a massive success, precisely because they all got so upset about it. Quibble with the list, rage against the list, suggest alterations to the list, send death threats to the people who compiled the list—just as long as you pay attention to the list. (The Atlantic had similar success earlier this year with their own list of the great American novels. Everyone agreed it was terribly thought out and missing all the really important works, even if nobody could agree what those actually were.) This is why they put out a compendium of the greatest books in a century that’s 76% of incomplete, rather than, say, the 14th century, which produced some of the greatest books ever written and is also helpfully available in full. You can try to imagine how that list would go. Obviously the Divine Comedy would take the top spot, for the same reason My Brilliant Friend did in the real one. (That is, because the New York Times has to survive in a city full of violent Italian mobsters.) Second place goes to the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, because we mustn’t be too Eurocentric, then the Canterbury Tales, then the Decameron, while all my favourites—the Mabinogion, Gawain and the Green Knight—are shunted to the back. But how many of the people currently squabbling about the top 100 books of the 21st century would be joining in the argument? In fact, how many of them have read a single book from before 1800?

To be clear, putting older books on your lists doesn’t improve anything. Harold Bloom stuck an immense list on the end of The Western Canon, well-stuffed with the past. But there’s something weirdly pointless about it: his canonical list of Greek tragedies, for instance, consists of essentially every single Greek tragedy that survived. Of the Romans, he thinks you should read Terence, Horace, Virgil, and Ovid. Consider Wordsworth. Consider Keats. Bold stuff. But he’s trying to establish a canon, and a canon’s only really canonical if everyone can already predict exactly what’s going to be in it. If his list had told you not to bother with Homer, or if it were stuffed with the totally inaccurate books of medieval zoology and dream-interpretation I love so much, it wouldn’t have done its job. And its job is familiar: to get people talking about the list. Not an arrow pointing you towards something else, but an object in and of itself, a big medallion for you to wear around your neck. I don’t believe in the School of Resentment, it says; I uphold the canon. To his credit, Bloom ended up repudiating the list, which he claimed to have only added at the request of his publishers. ‘I’m sick of the whole thing. All over the world, people reviewed and attacked the list and didn’t read the book.’ Which is, to be fair, exactly what I’m doing now. But I refuse to believe he didn’t know exactly what would happen. His publishers certainly did. This is what a list of books is for. What did he expect?

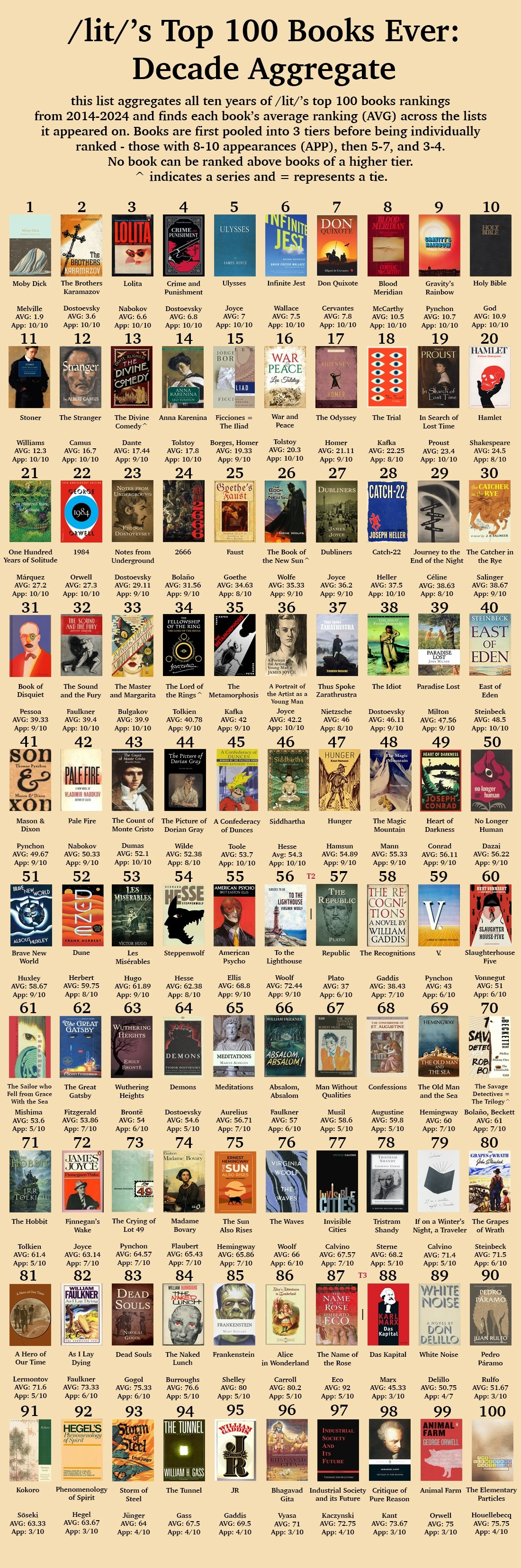

Anyway, the canon wars have moved on now. Bloom is no longer the standard-bearer for his faction. Instead, it’s this:

Every time this list starts doing the round, everyone always comes out with the exact same response, which is to say how surprisingly decent it is, especially when you consider that it came from 4chan. You’d expect Mein Kampf and Atlas Shrugged plus a load of manga and genre swill—but while there’s a bit of sf and a few right-wing favourites, they’ve actually come up with a pretty good list.

It is not a pretty good list.

According to 4chan, Lolita is the third greatest book ever written in human history. Better than Goethe, better than Shakespeare, better than the Bible. Does anyone actually believe this? Even the biggest Nabokov heads all seem to prefer Ada. But there it is. According to 4chan, every single great novel from outside the (broadly defined) West has come from a single country, which is—of course—Japan. They could have pulled Bloom’s excuse, that he was limiting himself to the specifically Western canon, but they couldn’t resist throwing Mishima in there. According to 4chan, there’s been no good poetry written since Paradise Lost, or at least none better than George Orwell’s Animal Farm. Meanwhile, the only two plays better than Animal Farm are Hamlet and Faust, and absolutely nothing as good as Animal Farm was written in the 920 years between the Confessions and the Divine Comedy, or in the 294 years from then to Don Quixote. There’s something weird about the works of philosophy in the list too. Zarathustra has enough literary quality that it still makes sense in a list mostly occupied by novels; the Meditations is a cheesy choice but sure; even the Phenomenology of Spirit is thudding and bloated and grand in a way that seems to echo some of the other great big thick books around it. But what the fuck is Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason doing in there? My edition is nearly nine hundred pages long, and every single one of them is crammed full of sentences like ‘The logical determination of a concept by reason is based upon a disjunctive syllogism in which the major contains a logical division (the division of the sphere of a general concept), while the minor limits that sphere to a certain part, and the conclusion determines the concept by that part.’ All very philosophically important, but I don’t think even the most fanatical Kant scholar would say it’s a good book, especially when they could have gone with Either/Or. Finally, according to 4chan, one-twentieth of the peak of humanity’s literary output was achieved by a single man, Fyodor Dostoevsky. He gets five spots in the list, as many as all the other Russians—Tolstoy, Bulgakov, Lermontov, and Gogol—combined. Poor Turgenev doesn’t even get a look in. Neither does Chekhov. Neither does Pushkin. Dostoevsky is simply not that good! No one is that good! But he’s become the symbol of a certain kind of weighty, serious literature, even though all his greatest works consist of one part devastating insight to nine parts hysterical landladies screaming ‘Wha-a-at? But this is madness! You’re prattling, prattling I say! Sheer nonsense!’ while our hero sits silently in a sofa and slowly turns white, then red, then blue. It doesn’t matter. For reasons mostly unrelated to his actual books, Dostoevsky has the right aura. In he goes, to spread through the list like black mould.

What we’re looking at isn’t really a list of the greatest books ever written, it’s a bunch of examples of one very particular type of book: the long, morose psycho-philosophical novel. Like every list of books, it’s an exercise in summoning an aspirational type. This time, it’s the brilliant sensitive young man, quiet, maybe lonely, misunderstood, a creature with hidden depths. The long, morose psycho-philosophical novel is what this type of person is supposed to read. This is why this collection of all the old canonical standards still has some very notable omissions. No Middlemarch: it’s too polyphonic, too relational, too much like the chatter of the high school cafeteria, which you, as a brilliant sensitive young man, are trying to escape. No Dickens, for the same reason. There are a few books that don’t meet that description, but they’re all some form of set decoration. You’ve got to include Homer, or people won’t take you seriously. You need the Bhagavad Gita to show depth. Chuck some Hegel in for roughage. But the set decoration still has to contribute to the general tone. That’s why the Critique of Pure Reason makes the list, but not Spinoza’s Ethics, which has a sharp mineral clarity but doesn’t manage to scratch 150 pages. Not long enough: it needs to be impressive. As it happens, I like a lot of long, morose psycho-philosophical novels, and I like a lot of the books on this list. It’s just very depressing to see them like this, torn out of the world that contained them, laid out motionless, one after the other, like props, like bodies in a mass grave.

I’m sick of lists of books. Reading lists, top tens, flowcharts, curriculums, canons, counter-canons, the lot. Pathetic activity. Someone could write out the name of every single book I really love, ranked impeccably, with no omissions and no interpolations, and I’d spit cold venom in their face. I think the only way to read with dignity is to read organically, genealogically, backwards, by touch. Not running down a list, but excavating, following the seams where words bleed into each other. When I was still quite young I found a copy of Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow. At that point I was very pleased with myself for being grown up, gradually phasing out Discworld for Ian McEwan, real books about real stuff like relationships and being wistfully middle-aged, all of it without a goblin in sight. And then, suddenly, I’m with Pirate Prentice who inhabits the fantasies of others, watching Freudians shovel cocaine into the flanks of the giant glistening adenoid that’s taken over central London. ‘Before the flash-powder cameras of the Press, a hideous green pseudopod crawls toward the cordon of troops and suddenly sshhlop! wipes out an entire observation post with a deluge of some disgusting orange mucus in which the unfortunate men are digested—not screaming but actually laughing, enjoying themselves…’ The whole book was like that adenoid, carelessly violent, swamping you in its unintelligible phlegm of words, but it was fun in a way I didn’t realise was even possible, let alone allowed. How did this book exist? What could have happened in the world to set the conditions this kind of writing? Which is how I found out about James Joyce. And when he also became inexplicable, I discovered the Flaubert of Bouvard and Pécuchet, and it’s still going on and on from there, backwards, tunnelling down, past Rabelais and Vico, heading somewhere I don’t know.

You must not start with the Greeks. Instead, at the start, you can have a few years to read contemporary fiction, all the stuff recommended by Barack Obama and the New York Times. There’s no point wasting too much of your youth with the present, though; you’ll be in some kind of present for the rest of your life. When you’re a bit older, hormonal, pissed off at your parents, obsessed with your own interiority, you can move over to the stuff on the 4chan list, 20th century tomes about being upset, and act very pleased with yourself. But after that you have to dig. You have to be serious to read without lists, but if you’re not serious no amount of lists would ever help you. End up wherever you end up, without any smug nerds or US Presidents to take the blame. Maybe right at the end, you can read the Epic of Gilgamesh, one last wail against death. And then, finally, with everything fitting together and nowhere left to go, there will be one brief bright moment in which the entire world makes perfect sense.