Confessions of a mask

Hiding underneath the mask is not a monster, but nothing at all

Kanye West goes on Infowars to praise Adolf Hitler from behind a black rubber mask. ‘I love everyone. Every human being has something of value they brought to the table. Especially Hitler… There’s a lot of things that I loooove about Hitler.’

Maybe this is a disease of brilliant, addled, sexually fluid men. Remember David Bowie in the 1970s, a moment of much more acute reactionary danger than today. ‘I believe very strongly in fascism… Rock stars are fascists. Adolf Hitler was one of the first rock stars.’ And in a way, he was right. Isn’t there something a bit Hitlerian about the whole scene of stardom? The idol on stage, the lights, the ecstatic crowds dancing around at his will? But in the end, Bowie walked back his comments. It wasn’t him speaking, he said, but a character: the Thin White Duke, a cold-burning star full of all the fascism latent in pop culture. ‘What I’m doing is theatre, and only theatre.’ He was wearing a mask.

So, what’s with Kanye’s mask? This is the first question he’s asked, before any of the Hitler stuff comes up:

ALEX JONES: Radio listeners, they can’t see you right now. This is a new look for you. KANYE WEST: Oh no, I’ve been wearing a mask for a while. ALEX JONES: Ah. KANYE WEST: Yeah. ALEX JONES: [Hopefully] This is an archetypal example of the mask is off, by putting the mask on? KANYE WEST: People can take it how they want to take it. It’s just, it’s interesting, if you look at a Michael Jordan or something, you load up all these pictures and he’s smiling, he’s holding a basketball, he’s jumping from the free-throw line—and you look at Phil Knight, you can barely see a picture of him, he’s got his face covered. So I don’t have to show my face. It’s me. That’s my right.

Real power, he’s saying, is invisible, and that’s what he would like to be. This mask is meant to obliterate the theatre of the person: it’s a refusal to enter the visible, which is also the sphere of exchange. I will not be a grinning commodity. I will not be bought and sold. A step back from saleable identity, from spectacle and display, into the hidden recesses of the subject. The Balenciaga x Yeezy DONDA face mask can be yours too for $160.

This is his account of things, at least. Others aren’t so sure. The mask certainly seems like a way of hiding, even erasing yourself. A year ago, before the abrupt turn to Hitler, Dean Kissick could write about Kanye and his masks:

When Kanye walked around the stadium this summer in a mask, it did feel like something important was taking place: that he was relinquishing a part of his identity. How could we even know that it was him behind the mask? He was effacing himself in the stadium. He was living there, in the ruins of his identity, in the stadium, trying to make great art. Trying, and failing, to make a record as bright as what he was dreaming of, or, perhaps, to make himself into the timeless work of art that might redeem his life. Eight years ago he was saying he was a god. Now he’s nobody, rising into the light.

But we lose more than identity when we lose our face. Like many Jews, Emmanuel Levinas spent the war as one of Adolf Hitler’s captives. As a French prisoner of war, he was spared Auschwitz and the mass exterminations, but maybe his entire thought is an attempt to reckon with what happened there, to find an ethics that would forbid a Hitler, and to put that ethics firmly at the centre of philosophy. He finds it in the face. From Ethics and Infinity:

The skin of the face is at its most naked and defenceless. The most naked even though this nudity is decent. The most defenceless too: the face carries within it a certain poverty; the proof of that is that we try to mask this poverty by assuming poses, an attitude. The face is exposed, vulnerable, as if inviting an act of violence. At the same time, the face is what prohibits us from killing.

From Totality and Infinity:

Infinity presents itself as a face in the ethical resistance that paralyses my powers and from the depths of defenceless eyes rises firm and absolute in its nudity and destitution. The comprehension of this destitution and this hunger establishes the very proximity of the other.

Levinas doesn’t treat the face as a totality: there’s the eye that sees (which has ‘the privilege of maintaining the object in this void and receiving it always from this nothingness as from an origin’), and then there’s the mouth that speaks. The face, for Levinas, cannot be seen, only spoken to. It’s speech that establishes the relation to the other. But the face is also the site of murder.

Kanye faces us without a face, and speaks. The mask blots out the face, with all its terrible incitements and demands; neutralised behind his mask, even a figure like Hitler is removed from ethics. He says he loves everyone, and maybe he does. But what is love without a face? The mask says that Kanye will have no sympathy for us, and we will have none for him. Maybe he really does want to disappear. Maybe the mask is his way of telling us that killing him is no longer forbidden.

Some masks only cover part of the face—which is, as Levinas understood, a terrain split between two zones, the seeing eye and the speaking mouth. (The nose doesn’t really belong to either; in fact, it doesn’t really belong on the face at all. Emoji, the simplest effective faciality-engines, are noseless. A nose communicates nothing except disgust, or, when elongated, untruth. At one point, Freud considered that the nose was actually a genital organ that had wandered north. And the nasal passages do contain erectile tissue, which is why your nose gets bunged up when you have a cold. Maybe this could explain some of the antisemite’s horrified obsession with that obscene, thrusting cock in the middle of the Jew’s face.)

Superhero masks hide the eyes: Batman, Captain America, Judge Dredd. The peaked caps of policemen in various despotic states do the same thing, especially when combined with sunglasses. The upper zone contains what’s vulnerable in the face: eyes meeting yours, naked eyebrows, knotted. Batman and the Gestapo officer appear only as a mouth growling orders. In masquerades, the upper zone is also concealed, and everything is suddenly permitted. But the lower face is not always so powerful. See Beckett’s play Not I, in which the actor is also reduced to a disembodied mouth, floating alone on a pitch-black stage, ‘faintly lit from close-up and below, rest of face in shadow,’ narrating events from her life and insisting they they all happened to somebody else:

… that April morning … she fixing with her eye … a distant bell … as she hastened towards it … fixing it with her eye … lest it elude her … had not all gone out … all that light … of itself … without any … any … on her part … so on … so on it reasoned … vain questionings … and all dead still … sweet silent as the grave … when suddenly … gradually … she realis … what? the buzzing? … yes … all dead still but for the buzzing … when suddenly she realised … words were … what? … who? … no! … she! …

I who am eyeless can fix nothing with my eye. A speaking mouth detached from the face is always something broken. It lacks a self.

What about the mask that covers the lower face? Doing this always seems to inspire some level of outrage: witness the periodic bouts of European fury against the Islamic veil. (Burqa porn is also extremely popular, probably among some of the same people.) But two years ago we were all wearing them, to protect other people from the viruses swarming in our throats. This, too, made a lot of people very unhappy; despite all the earnest boosterism about helping others and saving lives, wearing the mask always felt like being the opposite of a superhero. You’re trapped in too much self; you drown in it. In 2020, Amber Frost wrote:

I hate the masks. I hate wearing them, I hate seeing other people wearing them, I hate seeing the discarded ones all over the ground. I fucking hate them. I feel like I live in an open-air hospital, or a particularly cosmopolitan leper colony. I miss human faces very badly, and I hate the sensation of being trapped in a breathing swamp of my own self, as each damp exhale rolls back onto my face.

There are a few people still wearing masks. The elderly, the immunocompromised. But also children, and especially teenagers. Many of them like the masks, or at least they hate them less than any other available option. They’re shy, spotty, and insecure; the lingering afterlife of a global pandemic is a good enough excuse to protect themselves from the terror of being seen. Online, they face each other with something that is not their face, tucked and tweaked by a helpful AI until it looks more like the version of themselves they imagine. Is there a real world that ought to be any different? They’re willing to forgo the face’s invitation to an ethical relation to the other, if it means also getting rid of its invitation to violence. There are classrooms full of children, all marinating in their selves, hiding.

But a mask does not only hide and conceal. It’s also, as Bowie told us, a prop: a piece of theatre. Towards the end of 2020, when the borders first started to open up, I made it to New York again. In London, we’d all stopped wearing our masks outside; we knew that the risk of outdoor transmission was minuscule. In New York, everyone still had them, and my friends snapped at me to keep my mask on. The facemask had assumed a symbolic function. Everyone knew it wasn’t medically necessary, but it still announced to the world who you were, your role in the play. If you wore the mask outside, you were a good person. If you didn’t, you might be a Trump supporter.

It’s not always so easy to distinguish the mask from the face.

Long before he started wearing masks, Kanye West transformed hip-hop by making it personal. He dropped the mythological register of rap, the storytelling, the violence, the luxury ship catalogues, for something closer to everyday psychology. He talked about the ordinary texture of life. He was the avant-garde for our age of mandatory self-disclosure, where every celebrity figure has to speak out bravely about their experiences, squirm like a rat on a dissecting table. From epic to novel, and from mask to face. Naked unhidden flesh:

She find pictures in my email

I sent this bitch a picture of my dick

I don't know what it is with females

But I'm not too good at that shit…

But remember that for his very first single, Kanye performed with his jaw wired shut: adopting the rictus of the mask.

I’ve known some highly lauded personal writers, people who churn out books and essays all about themselves and their inner lives, mercilessly exposing all their faults and failings, their bad decisions, their cruelties, all the ways they’ve been broken… Unflinching, unguarded; bitingly honest, searingly honest. It’s always, always a lie. Honesty is hard, incredibly hard, and you can’t do it to a deadline twice a month. These people are always performing a myth of the self: they are masked. The faults and failings they describe are not their own, but a more interesting and romantic way of being fucked up that they’ve imagined for themselves. What’s worse: when you try to actually talk to these people as they are, you might find that hiding underneath the mask is not a monster, but nothing at all. They do not understand themselves because there’s nothing there. The mask is all there is.

The Greeks had a single word, prosopon, that meant both mask and face. According to the Council of Chalcedon, Christ has two natures, but one prosopon, one person: one face, one mask. It was the Romans who introduced a distinction. While Greek actors were frozen in clay, with the tragic hero wearing his agony from the start, in the Roman theatre they wore masks with huge apertures around the eyes and mouth, so the vultus, the real facial expression, could be seen. The face, not the mask, did the work of communication. The Romans knew which was which.

We seem to have forgotten. What does it mean for us in the present to speak or write personally? Person is a strange word; its singular and plural have very different origins. People comes from the Latin populus, which originally meant army. Person is from the Middle English persoun, meaning human being, which is from the Norman French parsone, meaning human being, which is from the Latin persona, meaning mask.

In the early 20th century, European artists started looking at African masks. Maurice de Vlaminck saw one at a bistro in Argenteuil, ‘on a shelf behind the bar, between the bottles of Pernod, anisette, and curaçao.’ André Derain bought one from Gabon and kept it in his home, where it was glimpsed by Picasso. Ah! The primitive! The innocence! The light of hotter suns! So you get modernism: maybe not stolen wholesale from African art, but tugged towards Africa and abstraction as an alternate centre of gravity.

Still, these Frenchmen didn’t understand what they were looking at. They kept seeing African masks as volumes, stacks of space, representing the human face—because they only encountered them as objects, on a shelf, propped against the wall. But wherever ritual masks exist, they’re used in dances, and usually to effect the dancer’s transformation into an animal, spirit, or god.

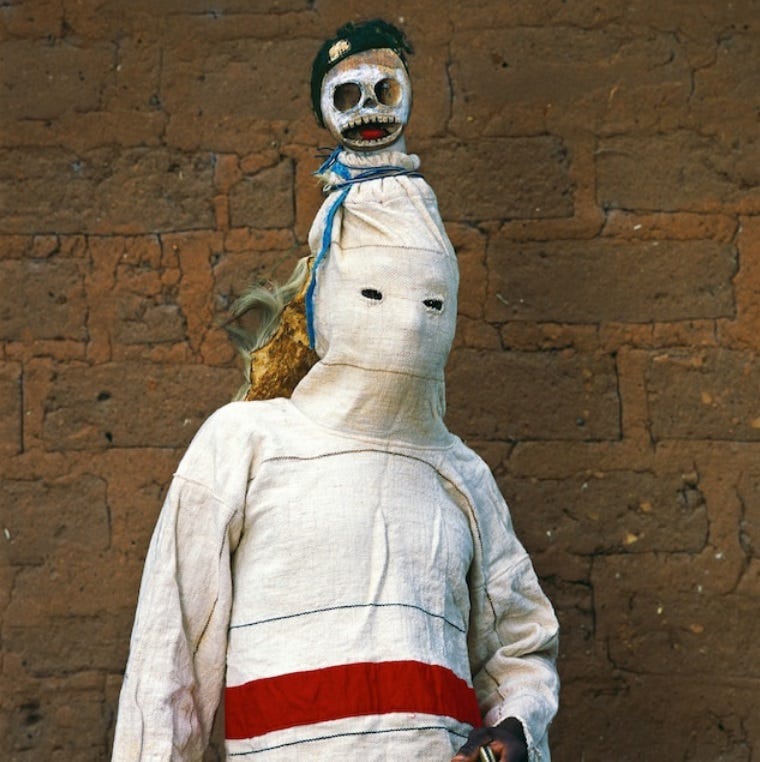

The Bwa plank masks or nwantantay above are the faces of the do, nature-spirits. ‘Ineffable, untouchable, invisible, inaudible. Believers can sense their power in a summer storm, when the earth shakes with the crash of thunder, and sheets of rain sweep across the hot dry fields. How are we to communicate with the spirits?’ Not by making pictures of them, since they don’t look like anything, but by becoming them. Griots surround a dancer dressed in long, shaggy raffia strands, who winds and twirls like the wind, like a thing that can’t be seen. The mask is not a novel way of depicting the human face: it is a face, just one that isn’t necessarily human. A face for the faceless. And it’s not contemplated in terms of its abstract or imagistic representations; it dances. Not a static object composed of volumes, but a living god composed of speeds.

The societies of the old world—Europeans and Africans both—edge their way around this stuff, they deploy their metaphors in wood and clay, but you can always trust the Mexica to cut through all the bullshit and show you things as they really are. Aztecs made objects that are still referred to as masks, beautiful jade and mosaic faces, but they had no eyeholes, and nothing strapping them to the head: they were not made to be worn. As Inga Clendinnen explains, the real masks were gorier:

Xipe Totec, the Flayed Lord, god of the early spring, was always represented with the same terrible simplicity. We see him as a naked man enveloped in the flayed skin of a human, the stretched face skin completely masking the living face beneath. (Typically the hands of the flayed victim dangle uselessly at the wrists, still attached by strips of skin, and the skin was worn with the bloodied side outermost: Xipe, like all the maize representations, was a red god.) Faithful to our view of things, we identify the god as the living man within, regarding the enshrouding skin as an external thing. But that is not what we are being shown, again and again, in his image: Xipe Totec is presented before us immediately, as the ‘dead’ enveloping skin.

At certain set times in the year, human beings would become ixiptla, or images of the various gods. They would be worshipped in the streets, bathed and perfumed, hung with flowers and quetzal feathers and precious stones. But they were still only images, until the moment their heads were struck off, the skin was stripped from their bodies, and a naked priest wore it over his own, ‘with its slack breasts and pouched genitalia, a double nakedness of layered, ambiguous sexuality.’ The priest danced, and the wet dead skin was no longer an image of the god, but the actual god.

But sometimes, even Europeans get it. English fox hunters use a specialised, ritual language. The dogs that chase after the fox are not dogs but hounds; the only dog is the fox itself. The fox’s tail, when taken as a trophy, is not a tail but a brush. Its head is not a head, but a mask. A dead fox is a mask for the trees, the earth, God, and itself.

These are the only masks that can be viewed in stasis: the masks of the dead. Death masks have a long history in Europe, but the real masters were in New Guinea. There, skulls were overmodelled with beeswax or clay, and decorated with feathers, cowrie shells, stones, seeds, beads, fur. The human face rearticulated, in death, into beautiful new shapes.

This might be the origin of the mask. The oldest masks ever discovered are 9000 years old, and they were found just northeast of Jerusalem in presently occupied Palestine. The people who lived there, who may have been the distant ancestors of the Jews, which is to say my distant ancestors, carved these masks with their delicate and creepy teeth out of limestone: too heavy to actually be worn. But they have holes around the sides; clearly, they were strapped to something. At the same site, though, researchers unearthed skulls: lots of skulls, mounted on small pedestals. This place was, like Mesoamerica or New Guinea, home to a skull-cult. Again, they were plastered: carefully wrapped in lime and clay to imitate a living human face. The eye sockets were filled with seashells.

Kanye West, who says he is a Christian, should know that the names Calvary and Golgotha, the site of the Crucifixion, both mean place of the skull. Traditionally, that place is identified with the hill that was razed to build the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, but really we have no idea where the Crucifixion took place. All we know is that it was a spot of land (not even necessarily a hill) not far from Jerusalem. But in a surviving fragment of Origen’s third-century Commentary on Matthew, he writes that a ‘Hebraic tradition has come down to me that the skull of Adam, the first man, was buried there where Christ was crucified.’ Early Christian representations often show the blood of Christ, the second Adam, dripping down to wet the skull of the first. They do not show the father of us all as he was. Plastered in lime, with seashells in his eyes.

The very first masks might also have been worn by the dead. A face for the corpse as it decomposes, a face you can speak to. A living face.