Numb in India, part 4: Dharma police

Why the caste system is much weirder than you thought

Once again, Numb at the Lodge is on holiday. Paid subscribers can join us in a brain-melting tourist odyssey across the past and future of Indias real and imagined. Last year, in China, free subscribers got to peek behind the curtain in a free post on the insanity of the Chinese language. This post on the caste system is also free, but all the best parts of all the others are behind the paywall. If you want to come along, all you have to do is click the button below:

Today I’m writing from Jaisalmer, a fortified knuckle of sandstone in the middle of the Thar Desert. This city was founded in 1156 by the Bhati, a Rajput clan pushed into the desert from their Afghan heartland by waves of invaders from the steppe. According to Orlando, for the people of Jaisalmer not much has changed since. Don’t be fooled by their clothes, he told me. Don’t be fooled by the fact that they’ve all got iPhones. Out here, the veneer of modernity gets real thin. This is a closed society. Inside their heads—and here he tapped against the side of his own head—it’s still 1156.

I met Orlando in a tiny bookshop-café tangled up somewhere in Jaisalmer’s knot of alleys. This is a weird place. A lot of the streets here don’t have names: even on Google a bunch of addresses simply consist of ‘near the Lakshmi temple’ or ‘near the eastern wall.’ The postman knows where it is. But it meant I only got one conversation with Orlando, because when I tried to find that bookshop-café again, it was unreachable. I just kept turning one corner after another onto a succession of charming alleyways lined with ornate overhanging balconies, all baking and silent in the forty-degree afternoon, none of which contained my destination. I was circling the little red pin on my maps app, sometimes coming extremely close, sometimes landing on top of it, but somehow the actual place was nowhere to be seen. It had absconded from Euclidean space. It was accessible only via some special alley, running at an angle slightly against the grain of the rest of the physical universe. But I remember the place. The bookshop sold what every bookshop in every tourist destination in India sells: the Bhagavad Gita, Shantaram, and Atomic Habits. They also did a decent stuffed paratha, and a little notice explained that if you dobbed him a few hundred rupees the owner would drive you out to his village in the desert and introduce you to his mum. There was also a Polaroid of the owner and Orlando posted up near the entrance, although I didn’t really notice it until after I’d met the man himself. Maybe met is the wrong word. What happened is that while I was midway through my paratha, Orlando entered and started talking to me. He continued for maybe two hours, at which point I said that I probably ought to get going. About half an hour later, I actually left. Maybe that was rude of me, leaving. Maybe that’s why I haven’t been allowed to return.

There are two types of people who will just talk at you like this, going through their entire life story without ever stopping to ask you a perfunctory question about yourself. Old people do it, and Americans do it too. Orlando was both. Fortunately, his life story was interesting. He came into the café plump, pale, and sweating; smartly dressed, with his linen shirt neatly tucked into his cargo pants, but a big crunchy bucket hat on his head. He never told me exactly where he was from, just that he had quit the United States and had no intention of ever, ever going back. He lived in Hội An now, in a medium-sized apartment that he showed me through the many, many pictures on his phone. Here’s the bedroom. Here’s the bathroom. They both had the exact same white marble tiles on the floor. Isn’t it beautiful? he kept saying. He said that the American Dream was no longer possible in America; you had to go to Vietnam. He showed me a picture of his fridge-freezer. That’s it, he said, wide freezer, there’s a grocery store on the ground floor of my building, I don’t even have to go outside: that’s the American Dream. But he’d only recently discovered that the spirit of liberty is still alive on the Thu Bồn Delta: before that, he’d spent five years living in Jaisalmer. It hadn’t worked out. There had been some catastrophe, some nameless bad thing had happened, and the people of this tiny hairball of a city had forced him to leave. But even if he couldn’t live here, he still kept coming back, for a month at a time, to check in on his old friends. Or to let his enemies know that they still hadn’t won.

I had to piece together Orlando’s story from the various little crumbs he dropped here and there in his long ramble, but I’ll give it to you in chronological order. Orlando had only recently retired from his job somewhere in the blandness of America when he got some very bad medical news. He responded by buying a plane ticket. Over the months that followed the medical news got worse and worse and his tickets got more and more expensive, until eventually it got so bad that he bought a one way flight. His wife didn’t approve. She still had a life. Whatever it was Orlando was doing, she’d had enough; she wanted him to come home. So that was it: after forty-eight years together, after everything they’d been through in that time, he divorced her.

Orlando drifted weightless around the world until he finally came to rest in Jaisalmer. He loved it here, this squiggle of old, old streets almost chiselled out of the rock. And he was welcomed, at first. Jaisalmer runs on the tourist industry, now there are no more camel caravans crossing the Thar Desert. According to Booking.com, this is one of the ten most welcoming cities on the planet. But the people of Jaisalmer expect their visitors to come, have various wonderful experiences, buy lots of tat, and then, crucially, leave. Orlando wouldn’t leave. He rented a room from an ancient, impoverished Brahmin woman inside the fort and started trying to worm his way into the actual life of the city. Accompanying his landlady to funerals. Eating meals with her. This made people antsy. Jaisalmer, Orlando kept telling me, is a closed society. Anyone with money can stay in its hotels, but only Brahmins and Rajputs are allowed to actually live inside the fort. Orlando was crossing a line. Eventually people started asking him what it was he did for a living. They weren’t making small talk: they were trying to place him in the caste system. They were trying to work out what sort of creature he was. But Orlando is an American: he comes from the shapeless world. I don’t do anything for a living, he told them, I just exist. Only one of his new neighbours was smart enough to ask: so, what did you do before you did nothing? Orlando fobbed him off too. Eventually, the head of the local Brahmin clan took him in for an interrogation. When you die, the Brahmin asked him, do you want to die in America or in India? Orlando told him that he was never going back to America. He lived in India now, and he wanted to die here too. The Brahmin wasn’t finished. When you die, he said, do you want to be buried or burned? Orlando pretended to think about it. I reckon burned, he decided. And when you’re burned, the Brahmin said, do you want the ashes to go in the ground or in the water? Orlando mulled this one over for a while. You know, he said, I’d never really thought about it, but my gut is telling me the ashes should go in the water. And that was it. The clan accepted him. He could stay.

But it’s dangerous, telling an American that the clan accepts him. Every single American goes through life nurturing the secret hope that some clan of brightly-dressed indigenes will some day realise that he has the spirit of the coyote, just like them, and adopt him into the tribe. It’s part of that colonial complex they have. Sooner or later, your American will get weird and start pushing boundaries. Orlando started pushing boundaries in very short order. All of this had happened in late 2019; a few months later, suddenly everyone in the world was confined to their homes and Jaisalmer’s tourist trade dried up overnight. For a town that produces nothing except beauty, this was very bad news. Orlando holed up in his landlady’s empty apartment, just the two of them in the dark, in a city gone silent. Everyone was suffering, pawning their gold jewellery to make it through the year, but unlike all his fellow clan members Orlando had a big fat American 401(k), and far away in New York the stock market was booming. A good chunk of it ended up in his landlady’s pockets. She was very grateful. She thanked him the only way she could: by performing puja to him, tying a rakhi around his wrist, and declaring him to be her brother. This, Orlando told me, was a big deal. Brother-sister relationships are not taken lightly in Hinduism. It might have been less serious if he and the landlady had just had sex.

Orlando’s version of events is that her clan were upset at being upstaged: that he’d stepped in to help this old woman when none of her actual family would. Shame becomes anger. And that might well have been part of it. But try to see things from their perspective. You make your accommodations with the tourist trade, but if you’re a very traditional Hindu—and a lot of people in Jaisalmer are—then all foreigners are technically outcastes, mleccha, impure, untouchable. Technically, Orlando and I and all the other rich Westerners who descend on this town to take photos and spend money occupy the same caste position as the shit-haulers and carrion-eaters, the people too impure to live in the village, who have to bed down with pigs in the filth-heaps outside. No one’s so strict now, obviously. You make your accommodations. Break bread with the rich outcastes, dress them up in colourful turbans, and always, always smile. You’ll even accept this one funny mleccha as an honorary member of the clan, a kind of animal mascot, like the goat that’s a sergeant in the Indian Army. But if he’s a brother, that means you have actual kinship relations with this creature. Suddenly it’s not a game any more. Word got to Orlando that he was no longer safe in Jaisalmer, and if he knew what was good for him he’d get out. So he did, in a hurry. He wiped his hard drive, carried his clothes and gadgets out of the fort, and gave them to a Muslim family with instructions to donate it all to the poor. Straight to the airport from there. Off to Vietnam, where the Communist Party is in power and the American Dream is alive: a normal, modern society where the world is nice and shapeless and anyone can rent an apartment from anyone else.

When I left, there were sonic booms overhead. Jaisalmer might be a medieval town with a medieval mindset, but it’s also a frontier town now: its isolated spot in the middle of the desert puts it right near the border with Pakistan. On the streets below, Brahmin clans protect the old ways in their half-rotten homes. Up above, the Indian Air Force flings billion-dollar fighter jets against the sky.

Orlando isn’t the only American I’ve encountered out here. Back in part two I talked about learning the terrible secret of the Sun in Sawai Jai Singh’s city of Jaipur, but I didn’t mention that while I was there, entirely by chance, I ran into my friend Meagan Day, who you might know from her excellent labour reportage for Jacobin. Meagan was in India for the annual conference of the Global Labour University, which was held this year at Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi. At JNU the walls were painted with the words Workers of the world, unite! in English, Hindi, and Malayalam, and there were talks from union organisers who’d been through truly terrible things in countries where they break strikes with clubs and guns. After the conference was over, she had a couple of days free, so she went to Jaipur to see some forts and palaces and gold and jewels. A few days for the proletariat, a few days for the aristocracy.

It was fun: we were ushered through various gaudily decorated rooms of state by a mandatory tour guide who kept pointing out the best spots for selfies; later we were menaced by the monkeys at the monkey temple. But during her time in Delhi, Meagan had managed to pick up on some of what’s happening on the Indian student left. What’s happening is this: a lot of people involved happen to be Brahmins, and every six months someone notices this fact, at which point everyone starts violently melting down over casteism and caste politics, and then as soon as the situation stabilises it happens again. Most recently, some academics released a statement supporting hunger-striking students, in which they repeated a few of the students’ demands: a caste census, new student faculty elections, more sensitivity trainings, etc. The hunger strikers fid not take kindly to that ‘etc.’ Posters on the ‘etc-ification’ of oppressed-caste issues started appearing all over campus. ‘It’s not just about the grammar of the English language; it’s actually about the grammar of Brahminical politics.’

According to Raja, our guide in Jaipur, caste no longer matters in India. He came from the Verma caste, traditionally goldsmiths. And he had been an artist; his works had been exhibited in Germany and the Czech Republic. As it happened, his daughter had just started art school herself, studying textiles. But Raja insisted that this had nothing to do with being Verma. The Verma honour a particular deity called Bhairava, or The Fearsome One, a black, gnashing, sword-wielding, dog-riding emanation of Shiva who once cut off one of the heads of Brahma during an argument. As a Verma, Raja would occasionally sacrifice goats to Bhairava, but his profile picture on WhatsApp showed his actual favourite god: sweet, horny, flute-playing Krishna, all big eyes and pink pouty lips. Raja said he had friends from every caste: he ate with them, he drank with them, and if his daughter wanted to marry a non-Verma of course he wouldn’t care one bit. All of that is gone now, he said. Maybe in the countryside it still matters, but not here. But it clearly matters in Jaisalmer, and it also seemed to matter quite a lot to the Bahujan student activists at JNU. Their convolutions seemed familiar. Meagan and I are both fairly old-fashioned, class-oriented leftists, and for a while in the long 2010s that meant you were drafted into a very silly ideological struggle between class and some nebulous thing called identity. As far as we could tell, something similar is happening in India: caste joins race and gender and sexuality in the big bundle of axes of oppression. But caste is also material: it all has to do with the work you do. It looks like class; it feels like something else. Everyone knows that there’s a caste system in India, but the more you learn about it the murkier things get. What exactly is this thing? Where does it come from? What does it do?

I think I’ve found an answer. But it’s not what you think. In fact, almost everything you think you know about the caste system is probably wrong. Most Westerners are aware that there are four castes, which are the Brahmins, the priests and scholars, at the top, followed by Kshatriyas, kings and warriors, then Vaishyas, traders and artisans, and finally Shudras, peasants and servants, with the Dalits or untouchables in a kind of conceptual refuse ground beneath the entire system. This fourfold system is called varna, and simple and easy to remember, but it barely exists and hasn’t really functioned for a very long time. The actual Kshatriya lineages are all long extinct, and there are hardly any Vaishyas either; even most relatively high-caste people are from Shudra stock. Varna is also hardly unique to India; essentially the same system organised the estates of the anciens régimes in Europe. The actual castes aren’t the varnas, but the jatis.

What is a jati? Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast included a hereditary clan of ‘Grey Scrubbers’ whose entire lives are spent cleaning the castle kitchens. ‘It had been their privilege on reaching adolescence to discover that, being the sons of their fathers, their careers had been arranged for them. Through daily proximity to the great slabs of stone, the faces of the Grey Scrubbers had become like slabs themselves. The eyes were there, small and flat as coins, and the colour of the walls themselves, as though during the long hours of professional staring the grey stone had at last reflected itself indelibly once and for all.’ That’s a jati. Imagine if every air-traffic controller had to come from one of the secretive families of air-traffic controllers implanted in every city, and instead of passing an exam they simply perform their mysterious rites before a tiny black idol of God in his form as a cosmic air-traffic controller, directing the movements of stars and galaxies from his terminal in the great control tower beyond the physical universe, and then the airports have to hire them. Now imagine the air-traffic controllers all refuse to eat in the presence of pilots, who are their social inferiors, and if the daughter of an air-traffic controller tries to marry a pilot, her parents might try to kill her. Also, one person can ‘be’ a pilot and another an air traffic controller, even though neither of them have been anywhere near an airport and they’re actually both just millet farmers. That’s a jati. There’s no single list of every jati in India, and according to a lot of experts such a list would be impossible, but depending on how you draw your definitions there are anywhere from 3,000 to 25,000 distinct endogamous castes. Water-carriers, barbers, spinners, dung-collectors, cannibals. And every few miles, the entire system shifts, and there’s a new and intricate balance of different castes, each with its own job to perform, its own internal laws, its own customs, and its own gods.

For slightly more clued-in Western observers, there have been two main approaches to the caste system. The first has been to see it as an expression of political and economic power relations. This approach is not always Marxist. Early European missionaries in India soon found that if they preached to the lower castes, the Brahmins would refuse to have anything to do with them, so the Jesuits started dividing themselves into castes and maintaining strict separation. Afterwards, they were accused of adopting heathen superstitions. (This happened to the Jesuits a lot, possibly because they kept adopting heathen superstitions. At the same time, over in China, they were happily taking part in Confucian sacrifices.) The missionaries replied that caste was a purely social distinction, not a religious one. For a long time, it was assumed by British administrators that the entire caste system had been invented by the Brahmins to entrench their social power. By Marx’s day, a few observers were starting to question this idea, but he was, unsurprisingly, on the side of caste as an expression of social divisions. In The German Ideology, he scoffs: ‘When the crude form of the division of labour which is to be found among the Indians calls forth the caste-system in their state and religion, the historian believes that the caste-system is the power which has produced this crude social form.’

I am still some kind of Marxist, so I am eventually going to conclude that caste is an expression of the division of labour. But I’m a bad Marxist, so we’re going to get there the long way, through the other approach, the one that involves ideas and ideologies and the thunder of animal-headed gods, rather than simple political and economic facts. And the division of labour we end up with might not be the one you’re used to.

Probably the best representative of the other side is Louis Dumont’s 1966 opus Homo Hierarchicus: The Caste System and its Implications. It’s an exhaustive study of caste as an ideology, and I’ve been lugging all five hundred and fifty pages around this vast country. In a moment we can consider whether Homo Hierarchicus is a good or useful book; the most important thing to know about it, though, is that it contains some really beautiful and incomprehensible French-structuralist diagrams, like this:

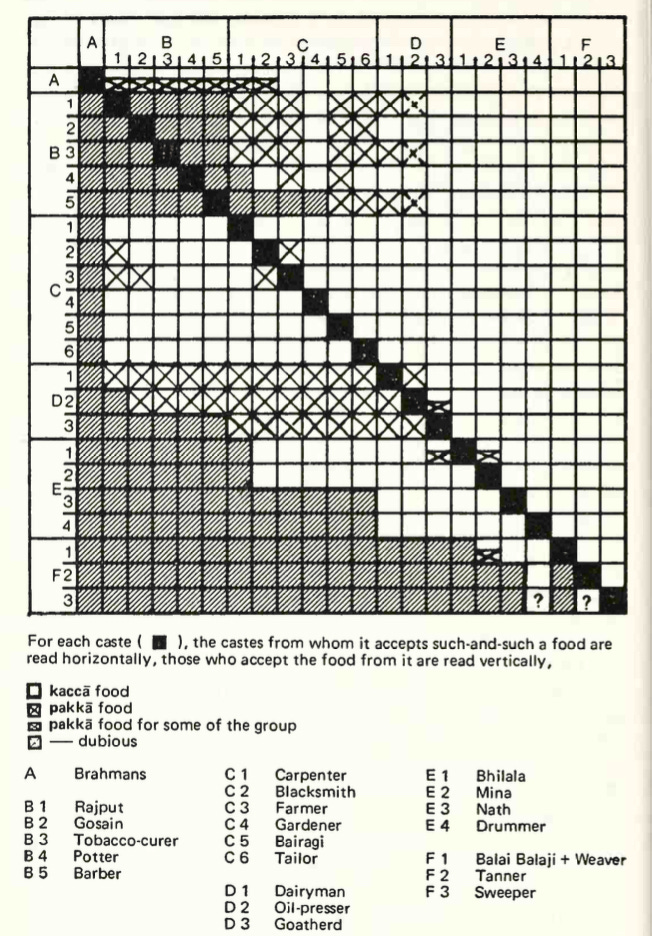

Dumont’s aim is to examine the caste system from the inside: instead of starting with big historical theories, he wants to reconstruct what it’s like to see the world through the eyes of someone deeply embedded in the world of caste. This is a difficult job. Europeans instinctively see society as a collection of basically autonomous individuals who have decided to come together for mutual gain. Indians are simply not the same. For Indians, any individual human being is just a piece of a rigid, all-encompassing hierarchy. And hierarchy is what Dumont identifies as the main principle of the caste system. Hierarchy looks a lot like ordinary power, but Dumont insists it’s something entirely different. There’s a division of labour, but ‘it eludes what we call economics because it is founded on an implicit reference to the whole, which, in its nature, is religious or, if one prefers, a matter of ultimate values.’ Instead, the basis of the hierarchy is purity. Dumont contrasts India with Polynesia, where commoners can’t approach the king because his mana is so powerful it might kill them. In India, meanwhile, the Brahmin is the fragile one. These people really can’t do anything; they’re so pure that even the shadow of a low-caste person can pollute them, at which point they need to take a ritual bath or rub themselves with one of the five products of the cow. But everyone is polluted by the castes beneath them, which is why people refuse to take water or cooked food or to share a pipe with anyone too far below them in the order of purity. (Obviously you can take raw food, otherwise only the farmers would be able to eat.) This is what keeps the whole thing functioning. So in the chart above, the potter caste will accept boiled rice from the carpenter caste, but not the gardener caste. This is how you can tell that carpenters are higher-caste than gardeners. But absolutely nobody will take food from the tanner caste, who work with dead cows and are therefore inherently impure and untouchable. This holds even though most untouchables didn’t actually do the impure work associated with their castes; they were usually just agricultural serfs. The stink of leather still clings to their skin.

Sometimes ordinary power does break through into the system. Rajputs are a powerful warrior caste, so they get sorted right below the Brahmins, even though they eat meat, which is polluting. Nobody wants to argue with a warlord. (Still, if you look at the chart, you’ll see that a lot of the vegetarian ‘C’ castes won’t take food from a Rajput, despite being notionally beneath them.) But that’s just power. Every village in India has its local landowning caste, and ‘almost any group whatsoever has, in favourable circumstances, been able to become the dominant caste in a given locality.’ The dominant caste can be gardeners or tobacco-curers or shoemakers, as long as there are enough of them, with enough weapons to keep everyone else down. VS Naipaul describes what a dominant caste looks like in an ordinary Bihari village. ‘Above the huts rose the rambling two storey brick mansion of the family who had once owned it all, the land and the people: grandeur that wasn’t grandeur, but was like part of the squalor and defeat out of which it had risen.’ Status in the caste hierarchy is something completely different, and sometimes it’s actively disempowering. The Brahmins might be at the top of the pole, but because of their impeccable purity they're often the ones who have to cook for other castes at weddings and funerals. Dumont notes that even in the bigger towns, a lot of restaurants and cafés advertise that they employ a Brahmin cook.

I feel bad for Louis Dumont. His model was based on a lot of intensive research, and it made a lot of sense, but it was doomed. Here he was, a French anthropologist, positing a coherent and self-contained structure that could be fully understood by the human sciences. The year was 1966. You might have worked out what’s coming next. Dumont couldn’t know it, but the entire time he was writing the book an enormous dark thundercloud was building up behind him. Its name was Jacques Derrida, and when it burst it would wash away Dumont’s entire thesis in a single terrible flood.

Today, basically every anthropological account of the caste system still finds time to mention Dumont, but only to totally disavow him. Everyone agrees that what he did was bad anthropology, barely any better than the dark old days of the discipline, when it was all about measuring various savages’ skulls to determine their exact IQ, or Indolence Quotient. So in my Blackwell Companion to the Anthropology of India, another big heavy book that’s been weighing me down in the desert, there’s a survey of the caste system by Robert Deliège, who begins by theatrically accusing Dumont of being ‘typical of the Orientalist tradition,’ ‘perpetuating the implicit assumption that social order is imposed upon individuals who are passive and static agents,’ and contributing to a racist vision in which India is ‘a world devoid of social change, economic development, equality, compassion, and communal solidarity.’ Others have gone further. There’s a strong current within Hindu nationalism that claims the caste system doesn’t even exist, because the entire concept of a caste system is intrinsically incoherent. After all, no possible theoretical construct could actually correspond to the free play that escapes the rigours of any particular sign. Pay no attention to the people living in filth and misery on the edge of the city. Don’t you know that the structure is always simultaneously destructuring itself?

But despite feeling bad for him, in the end I’m not sure Dumont’s project really works. He set out to explain the caste system in its own terms. This is a big job, but it’s possible. Read Inga Clendinnen’s Aztecs: an Interpretation, and you won’t just understand why the Aztecs practiced human sacrifice, you’ll start to wonder how our society manages to function without tearing out hearts for Tezcatlipoca. Dumont does not manage the same feat, because he almost entirely ignores the actual conceptual basis of the entire system.

Caste, he says, is a hierarchy based on ritual purity. And the concept of ritual purity does actually explain some of the more inexplicable things I’ve seen in this country. Like the filth. I might not be the first person to have noticed that public space in India is not hygienic. People keep their homes spotless, even if they’re living in a shack in the slums, and all the shops and restaurants and temples are impeccable too. But as soon as you step outside, it’s s game of dodge-the-turd, and not all the turds belong to animals. There are signs and murals everywhere begging people to care about their environment, but most people simply refuse. On the train here I was given a plastic tray with little compartments for the chana, dal, rice, chapati, and pickle, a kind of Indian bento box, and afterwards I was wandering around trying to find a bin that would take my dirty tray. Eventually the attendant snatched it from me, looked at me like I was an idiot, and chucked it out the open door of the moving train. It’s not like India couldn’t keep itself clean if it wanted to. This country has put a probe on the Moon. But it doesn’t want to. This is not a cultural value. And when you start thinking from the standpoint of ritual purity, this is actually completely reasonable. The world outside your home is inherently filthy and polluting, because this is where people of different castes mix. A Brahmin has to take a ritual bath whenever they go out. You could pick up all the litter and hose all the shit off the pavement, but it wouldn’t do anything at all to make those streets clean. So why bother?

But once Dumont’s introduced the idea of a purity hierarchy, he then spends the rest of the book thinking exclusively about hierarchy, and never really touches the notion of purity again. But what even is ritual purity? Where’s it come from? What’s it for? Dumont briefly plonks down the idea that ‘impurity marks the irruption of the biological into social life,’ and suggests that the ritual impurity attached to processes like birth, death, and menstruation ended up attaching itself to lower castes as a permanent condition. But he doesn’t seem interested in pursuing it. Still, there’s a weird undercurrent running through his book. Squint at it just right, and it starts to look like the caste system isn’t really about people at all. It’s about cattle.

There are a lot of cattle in Jaisalmer. Every city in India has its feral cows, but here the streets are full of them. They bellow in the mornings, they leave huge piles of wet shit in the streets, and they make it utterly impossible to get around. Every third alley is blocked off by a huge dumb animal, chewing slowly and displaying absolutely no interest in the world around it. You try to edge around the cow and it just stands there, indifferently occupying the entire width of the street. You try to move it along and it just whips its tail at you like you’re just another buzzing fly. The cows here are wonderfully gentle creatures: it’s hard for me to watch them tenderly, lovingly nibble at each other’s faces without feeling an immense stab of guilt for all those steaks and burgers and rendangs and bún bò xàos. But they are as thick as bricks, and there are more than five million feral cattle roaming the streets in this country, and this feels like a problem.

Everyone knows that cows are sacred in Hinduism. But being sacred does not always seem like it’s good for them. In fact, the way cows are treated here makes me almost want to abandon my Kantianism and become a utilitarian. The governing principle is ahimsa, non-violence, non-interference, which is not the same as ensuring the best possible outcome. So when a cow stops giving milk, instead of slaughtering it the farmer simply lets it wander free. A lot of these cows wander into cities, where people practice ahimsa by letting the sacred cattle eat from piles of stinking garbage on the ground. Cattle with their nuzzles in dumpsters, sweet tottering calves browsing through the filth. Instead of grass, these cows seem to subsist on paper. I’ve seen them munch down on coffee cups and newspapers and fliers. One cow that had found a trove of discarded books and was systematically eating its way through them all. Eating Shantaram. Eating Atomic Habits. The ribs show through the skin, but the bellies are tight and swollen. Their entire back quarters are splattered with their own liquid, diseased splatterings. It’s genuinely horrible to see. I try to remember that my own society does terrible things to these animals too, much worse than anything in India, but back home the torture and death takes place behind closed doors where nobody can see. But this is not exactly a comforting thought.

Here, though, it doesn’t matter where a cow lives or what it’s been eating: cows are pure, and cows are purifying. As I’ve mentioned, after contact with a lower-caste person, Brahmins can cleanse themselves with the five products of the cow. Those five products are milk, ghee, yoghurt, piss, and shit. Cow urine is used in soap and shampoo; it’s also sold as a medical cure-all. The BJP government has funded research into the cancer-curing properties of cow urine and dung. Floor cleaners made with cow urine have been used in public hospitals. Pathogens in cow piss include leptospira, which can cause jaundice, kidney and liver failure, and bleeding in the lungs, and brucella, which will give you endocarditis, pus-filled testicles, a swollen spleen, and abscesses in your brain. Swabbing down a hospital floor with the stuff is not a very good idea. So why are so many people convinced that it might be? Ask a Hindu, and they’ll tell you the cow is revered for its generous, motherly gifts of milk. That’s a very modern answer. It wasn’t always that way. A few thousand years ago, the people of India—like a lot of other people around the world—revered the cow as a sacrificial animal. The best gift for the gods. But it can’t just be any cow. ‘Speak unto the children of Israel, that they bring thee a red heifer without spot, wherein is no blemish, and upon which never came yoke…’ There are many similar requirements in the Vedas and the Shrauta Sutras. The animal must be clean, washed, perfumed, unblemished, uninjured, undefiled. Whatever goes to the gods must be pure. Or, in other words: purity is whatever gets devoured by the gods.

Ritual sacrifice isn’t such a big deal in contemporary Hinduism. But Dumont keeps finding inconvenient traces of it scattered about the caste system. Cows keep wandering into his alleyways. In that chart above, he has to distinguish between ‘kacca’ and ‘pakka’ foods. Pakka is safer than kacca; you can take it from lower castes. The difference is that kacca is food boiled in water, and pakka is fried in ghee. It’s shielded from contamination thanks to ‘the protective role of butter, a product of the cow.’ The system of mutual independence between castes in a single village—the barbers cut the tailors’ hair, the tailors cut the barbers’ suits, the blacksmiths make their scissors—is called the jajmani system. But the word jajman doesn’t have anything to do with bucolic village communities. It comes from the Sanskrit yajamāna, which refers to the person who commissions an animal sacrifice. In fact, the entire hierarchy of varnas originally centred around animal sacrifice. Vaishyas raise the cattle, Kshatriyas sponsor the festival, but only a Brahmin can actually plunge the knife into the animal’s neck. Today, of course, killing a cow is unthinkable. But Dumont does stumble on another weird parallel. The two worst crimes imaginable are the murder of a cow and the murder of a Brahmin. Their lives are, in some way, equivalent.

Just like Marx said, the caste system was called forth by a crude form of the division of labour. But that labour didn’t produce ordinary use-values: it produced sacrifices, flesh for the gods. It also no longer exists, not in any large-scale way, even if people like Raja still send the odd goat to Bhairava. Animal sacrifice declined, and the caste system emerged to replace it—with the position of the sacrificed animal, the pure and unpolluted meal for the gods, taken over by the Brahmin himself. Meanwhile, the Brahmin’s original functions—slaughtering cattle, butchering cattle, cutting the skin of cattle—were displaced onto the absolute lowest and most despised members of society. And around the same time, Hindu texts—which had, in the Vedic period, had very little to say about the subject—suddenly start talking almost incessantly about reincarnation and the transmigration of souls.

Whatever you’ve been told, India is not a fixed, hierarchical society. In fact, it has an extraordinary rate of social mobility. It’s just that instead of escaping poverty within your lifetime, you move up in the world through the mechanism of death and reincarnation. The caste system is a ladder. You don’t advance by being good, exactly: every social stratum has its dharma, the role it has to play within the social whole. The dharma of the king is to rule; the dharma of the barber-caste is to cut hair; the dharma of an airport security officer is to steal your shampoo; the dharma of a prostitute is to corrupt the souls of men; the dharma of an untouchable is to live in miserable squalor in the wastelands out of sight. Conform to your role, and in your next life you’ll be born a little purer, a little more refined, a little higher up the chain. It might take ten billion lifetimes, but once you reach the very top your purity is impeccable. You are clean. You are unblemished. There is nowhere else to go. You have made yourself a meal fit for the gods.

The whole of society is one huge sacrifice ritual. Maybe it’s the same for all systems of purity and stratification. Virtue politics, being a decent person, class society and its inequalities: a cleansing before the slaughter.

About an hour’s drive into the desert from Jaisalmer are the ruins of Kuldhara. One well-preserved temple and a few half-crumbled mansions in a landscape of broken walls. In the thirteenth century, this village was settled by the Paliwals, a Brahmin clan from the east. They lived there for hundreds of years, until, one night in 1823, the entire population vanished. They left their gold and their jewels and their lentils cooking over the fire. No bodies were ever found. At the very top of the class system there stands Kali, her fangs dripping with blood, the consumer of souls.