Numb in India, part 8: Love is all and love is everyone

Digging through the ruins of the hippie dream

Numb at the Lodge is approaching the end of its holiday. Paid subscribers can join us in a brain-melting tourist odyssey across the past and future of Indias real and imagined. The really good stuff is behind the paywall: this time, it’s a nausea-inducing thrill-ride through the esoteric history of the last four point two billion years. If you want to come along, all you have to do is click the button below:

Today I’m writing from the White Hermitage Ashram in the fictional Indian state of Parpakainilam. This is the international headquarters of the Joyousness Movement, also known as the Joy-Joys, which was founded in California in 1967 and is not a cult. They’re trying to teach me meditation. I sit on a tatami mat, dressed in scratchy white robes, while an ancient, liver-spotted sub-guru wanders around, giving instructions in his New Jersey croak. When you breathe in, he says, imagine yourself as a flowah. You’re just a flowah. Feel the lightness of your body: you are a flowah. So I imagine myself as a flower. My body splayed outwards, lacerated into petals. An enormous wet sexual wound at the centre. I imagine myself bursting into cocks. A ring of thick hairy cocks all around my sugar-seeping wound. That’s a flower, that’s what a flower is; it’s the genital organ of a plant.

I think I might not be cut out for meditation.

I try to do it the way they’ve taught me. I try to simply notice these images as they rise to the surface of my consciousness, not following them, not suppressing them either, not judging. It’s hard. You don’t know what it’s like inside my head. It’s a tiny place, and it keeps being invaded by a rush of spiky little demons: gnashings of fur and claws, some of them no bigger than flies, razorblades vibrating in the air, emitting stupid phrases in foreign accents, Russian, Chinese, or sometimes just wordless gibbering: my thoughts. At least, I assume they’re mine. Maybe in the same sense that the bullet that finally gets you is also yours. When they’re not exploding my body into bits and penises, my thoughts keep up a constant stream of inane bullshit. This meditation posture isn’t as comfortable as it was half an hour ago, they say. You’re hungry. You’re thirsty. You’re horny. You need to piss. One day, your skin will look like that sub-guru’s, all creased up like tissue paper, drooping from your spindly arms. And isn’t it funny to be here, in the depths of India, with so many Americans?

I’ve been thinking a lot about America in these meditation sessions, whether I want to or not. I’m thinking about the fact that when Columbus arrived in the New World, he was looking for India. The place he actually found was only an obstacle, a gold-bearing swamp between the man and his destination. The spices and mystery of India, where half-naked holy men sit on mountains and think about nothing. Maybe this is why, when the United States was established, it couldn’t just sit still in its borders; it had to keep going. Press westward, continue Columbus’s trajectory, towards California and the sea. ‘Passage O soul to India!’ Thoreau reading the Gita in his hut, making Walden pond into his own personal Ganges. Emerson building his new American cosmology out of refashioned scraps from the Vedas. And once the frontier closed, the tough, dusty, knife-fight encampments on that distant coast suddenly became obsessed with Indian spirituality. Reincarnation, past lives, the Universal Mind. The hippie counterculture is just the most recent model. Before that they were making tantric fire-sacrifices at the Jet Propulsion Lab; before that Swami Vivekananda had the state’s Victorian aristocracy abandoning their chintzy homes to wander the coast as holy beggars. California yearns across the sea, to India. The whole of America is just Europe’s yearning, across the centuries, for India…

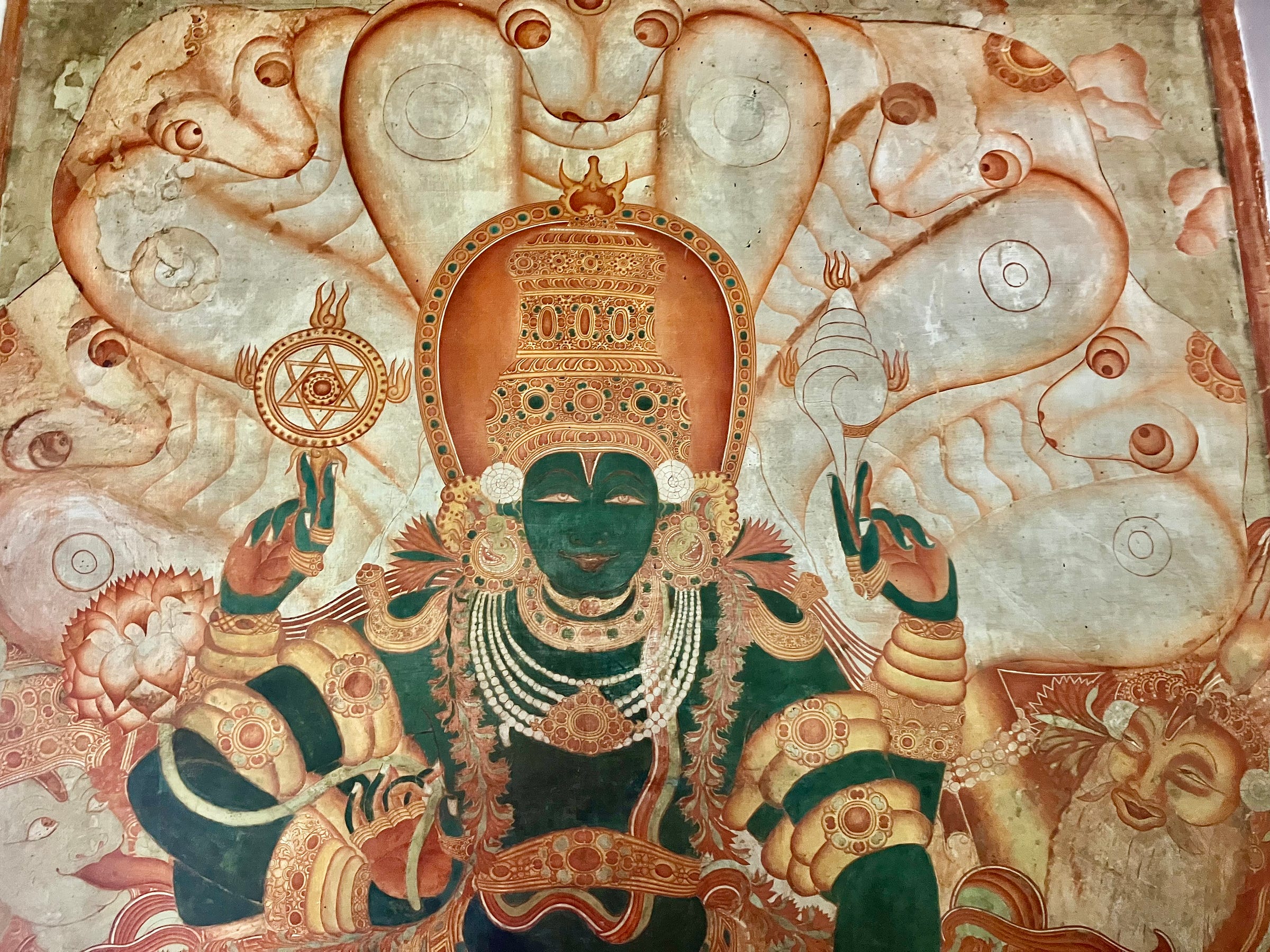

The fictional Indian state of Parpakainilam is in the south of the country, sandwiched between Kerala, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu. For thousands of years, great empires welled up and drained away in the valleys below. The Cholas, the Pandyas, the Vijayanagaras—while up in their inaccessible hills the Parpakai barely paid any attention. They were far too focused on chewing the mildly psychoactive bark of the tevaiya tree and building weird stone temples with twisting organic forms. Even now, this place is a nightmare to get to, but there is a rail line from Bangalore to Kanturava, the state capital. Every two days, a train clatters and wheezes up the mountains and over the rusting old bridges spanning the ravines. I stood in the vestibule, leaning out the open door, looking down into that sheer sheer drop where the green hills fade into mist. It took sixteen hours before we creaked into the station at Kanturava, the city of terraces and balconies carved into the wall of an enormous cliff, where the ladders have more traffic than the roads. Parpakainilam still barely considers itself part of India. It has the lowest enlistment rate to the Indian Armed Forces of any state, and the lowest voter turnout. None of the national political parties have ever managed to get a foothold here; instead of Congress and the BJP, the Legislative Assembly is split between the Wakefulness Party and the Party of Dreams. Parpakainilam isn’t even covered by the India Post Office; it has its own informal postal service, based on the ancient kaikku system, in which a letter is passed on, sometimes by hundreds of people, in the vague direction of the recipient. In the more remote regions it can take years to get a postcard, and this ashram is in a very remote region. It’s a six-hour drive from Kanturava, and after that you have to do the last three hours on foot, through forests and over rope bridges and past ancient stone statues wreathed in vines that inexplicably shoot fire from their mouths when you pass. It was not a nice journey. But I made here, to the White Hermitage Ashram in its damp valley, to learn about Indian mysticism and spirituality from the people who understand it best—that is, from Americans.

A day at the White Hermitage Ashram begins at five in the morning with two hours of guided meditation. After that, there’s a fire ceremony in which we worship the Universal Mind, incarnated as a marble statue of Guru Raj Hansi as he looked in the late 60s, long hair, long trailing beard, big handsome wide-open face. Then a simple, traditional ashram breakfast of foot loops and cap’n crunch, served with milk from the ashram cows and tevaiya bark for chewing, eaten in silence. After that, there’s six hours of uninterrupted work. Sweeping, cleaning, mucking out the cattle, hosing down the toilets, washing clothes, running the ashram’s social media accounts. (I keep asking to help with the animals; they keep forcing me to sit in a stuffy, windowless room and tweet.) At two in the afternoon we sit together and eat lunch, usually a big bag of crisps with more tevaiya. The next four hours are for personal reflection, meditation, study, and informal group exercises, before another aarti, a silent dinner of lentil burgers or tofu dogs, and bed. But it used to be very different. The White Hermitage Ashram is huge. Its dining hall is huge, its kitchens are huge, its laundry looks like an industrial operation. There are housing units in this valley ten storeys high. At its peak in the 1970s, there were six thousand people living, working, and praying here. Back then, before Guru Raj Hansi went into seclusion, a good chunk of the day was taken up by gurudarshan: thousands of Joy-Joys would arrange themselves around the Guru, radiantly nude, and just stare at him, enraptured, soaking up the blissful energies that radiated from his silent, smiling form. Then he would say a few, simple words. Joy is not something you are seeking, he would say. Joy is already here. This was usually followed by an enormous session of ecstatic group sex. The Joyousness Movement was casting off five thousand years of shame and jealousy. They were finding the joy bursting out everywhere from the look, the touch, the feeling of warm skin against your own. Sex is a form of meditation, one of the most powerful forms of meditation. Through pleasure or procreation, sex dissolves you into the great stream of being; it’s through sex that you can come to understand the first mahavakya, tat tvam asi, thou art that. You are the existent, you are the universal self, you are everything and everyone. Fall into an ocean of firm, tanned, supple flesh, without questioning whether this flesh you’re touching belongs to a friend, a stranger, a man, a woman, an adult, a child…

Apparently they do still have sexual meditation at the White Hermitage Ashram, but I haven’t seen any. Today there are about fifty Joy-Joys still here, and they are not as firm and tanned and supple as they were. They creak around the place in their orange robes, with trembling hands and purple blotches on their skin, and the ashram is in ruins. We eat in one tiny corner of the dining hall. The machinery in the laundry is all gummed up, leaking toxic sludge; we wash our clothes in the river. Trees are growing out of the roofs of the high-rises, as their roots slowly crack the concrete open. All the young sexy kids back in America are still into spirituality, but it’s a very different kind. Taylor Swift has not yet started making pop songs based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead. Sabrina Carpenter is not singing about how the physical universe is an illusion. The kids might still do yoga and say namaste, and they still think there’s a universal consciousness that’s ultimately identical with their own self—but they’re no longer interested in renouncing desire or achieving union with the divine. They don’t want to escape the material world. They don’t want enlightenment. They are driving their bodies like cars, and they have no interest in getting out. At no point do you have to go on any kind of pilgrimage to India. It’s all about manifesting: using the fact that you’re a facet of the Infinite Mind to get the stuff you want. More money, more Instagram followers. The question isn’t why Westerners became obsessed with Indian spirituality: it’s why we stopped.