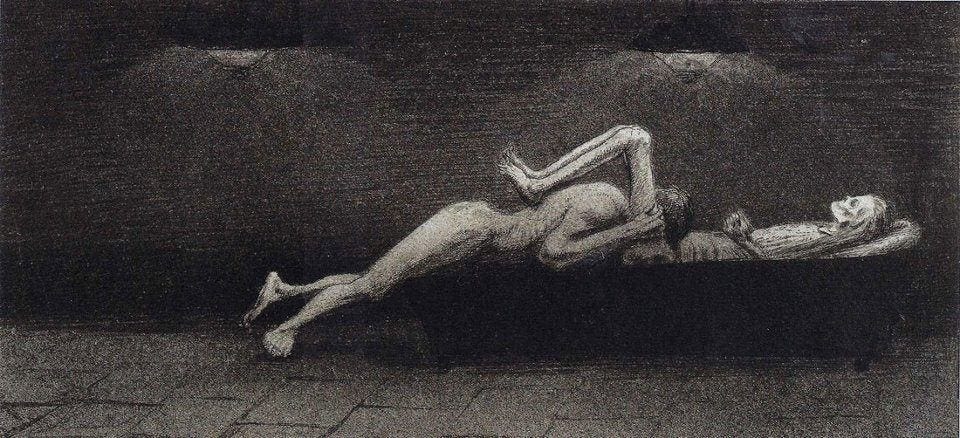

Strange News from Another Star, No. 2: Death

More dispatches from the other world

Bulletin

This is the second edition of Strange News from Another Star. My subscriber count has nearly doubled since the first instalment, so a recap: Strange News from Another Star is a kind of collective dream journal, based on the suspicion that dreams—even other people’s—are more important, and more interesting, than conventional wisdom would have you believe. Each month, I hope to dig into some specific aspect of dreaming: the themes that crop up again and again, the mechanics of it all, or scraps from the history of oneirocriticism. Last month’s edition was about the relation between dreams and the waking world; this month’s is about death.

SNAS No. 3 will be about dreams and messages. In basically every human society, (some) dreams were thought to be messages: communications from the spirit world, or the gods, or God, or even from other living people plugged in to the great communications network of sleep. I am interested in dreams that seemed to be unambiguously telling you something (Tony Soprano with his fish), and dreams that turned out to be in some way prophetic—but I’m also interested in messages within dreams. In my own dreams, I’ve received important-seeming information in emails, letters, through a kind of steampunk fax machine, and coded into a receipt. In one, I kept receiving handwritten notes telling me that I had ‘now become truly obese.’ In another, an international Ponzi scheme somehow revolved around a single quote in a collection of Henry Kissinger’s aphorisms, in which he said of the Donbass: ‘We need that coal. And, I’m told, the dream of human freedom is incomplete without Luhansk.’ I once dreamed that the ingredients list on a bottle of shampoo contained an urgent message from my brother informing me that our entire family was directly descended from Hitler. And so on.

If you’ve had an interesting message in a dream (or just an interesting dream), I’d like to hear about it, and apparently there are thousands of other people who would too. If you’re reading this in your email inbox, you can contribute to Strange News from Another Star by simply replying to this email. Otherwise you can email me at samrkriss [at] gmail dot com. (Please don’t forget the r; I don’t know who owns the samkriss email address but I think they get a lot of my mail.) Or you could just click the big button right here:

If you don’t include a name, I’ll assume you want to remain anonymous, but if you do give one I’m also very happy to link to your blog, Substack, music project, unhinged manifesto, terrorist cell, etc. If I publish your dreams, I might reproduce them in full, quote from them, or summarise; I might make some light edits for grammar and concision and so on; I promise not to substantively alter anything you send.

This edition is in three parts: one on dying in dreams, one on being visited by the dead, and one with some other miscellaneous stuff I found interesting. Because I want as many people to participate in this thing as possible, almost all of the first part is free for anyone to read. Because I am trying to wring money out of you, the rest is not. Because I have a particularly evil mind, I’ve put the paywall somewhere really, really annoying. I am holding your own dreams for ransom, and it’s all to manipulate you into pressing this button:

By the way, since we’re all here, I thought this would be a decent place to mention that over the past few months, I’ve had some essays published in a few other outlets, and I may as well wave them around in your face:

For The Lamp, I wrote about the Epic of Gilgamesh and the inevitability of death. The Lamp is a Catholic publication, and I am not a Catholic; I assume that most of their readers believe there is some kind of afterlife waiting for them when they die, and I do not. The piece is basically an attempt to communicate some of the terror of mortality to people who think they are immortal, but I also suspect that some people simply are afraid of death and others aren’t, and whether or not you believe there’s anything nice on the other side has basically no bearing on it.

For Justin EH Smith’s Substack, I wrote about the Tarot. The piece is weird and I won’t attempt to summarise it. I find it hard to imagine that there’s anyone who’s interested in what I’m doing here who doesn’t already read Justin, but if you don’t, then go now, go and subscribe at once.

I wrote two features I’m quite proud of for the Spectator, one on The Line, the utterly nightmarish linear city being built in Saudi Arabia, which I admire despite all my better instincts, and one on videogames and war, which are both terrible evils that any future socialist order must wipe off the face of the earth.

For The Point, I wrote about the literature of mass shootings—specifically, the question of why there isn’t any. What really makes the United States unique is not that this is a society that murders its children, but that these murders can happen and mainstream literary culture has nothing to say about it. For the most part, we leave the literature of mass shootings to YA novels and to the shooters themselves. This strikes me as a bad idea. (There’s also some bonus material in there about dreams.)

For the Telegraph, I interviewed Graham Hancock, the journalist who’s pivoted to insisting that there’s an advanced Ice Age civilisation buried in our deep history. I don't think I can subscribe to his particular model of history but he's an interesting guy and was fun to talk with.

Finally, for Glenn Greenwald’s Substack I wrote about antisemitism, and the hideous contrived spectacle of the UK’s Labour antisemitism controversy. (Content warning: politics.)

That’s all my news from the waking world. On into the night.

Dream of the month

Last month, I asked if any of you had any interesting dreams, and you did. I was basically overwhelmed by a glut of deeply weird stories, some of which are relevant to this month’s topic, and some which aren’t. If you are in the latter group, remain calm. I am holding onto your dreams, and I fully intend to publish them when the time is right. However, there was one from the last month that was strange enough that I wanted to share it right away, so I may as well institutionalise the process. The first SNAS dream of the month is from Brendan:

I was at a big open-air market in China. At one point I walked by a vendor, an old woman, selling beauty products. She tried to get me to come into her stall to sample some things and I initially resisted, but eventually, sheepishly, went in. She started showing me all of her lotions and perfumes and powders and finally, she pulled out a huge red vat of what looked like vegetable shortening. She went on to explain that it was meant to be applied inside your foreskin, and that my girlfriend would love it because it would make me taste better when she went down on me. She asked if I wanted to try a sample and I said no, but at this point there was a crowd gathering around the stall and no way for me to leave. She put on a pair of blue latex gloves (not the kind a doctor wears, but the kind a mechanic wears—dark blue, very thick) and I let her pull my pants down. My foreskin was the size of a Pringles can, which seemed natural and not surprising to anyone. She then proceeded to take handfuls of this Crisco-looking stuff and slather a thick layer of it onto the inside surface of my massive foreskin, which had a red, puffy, brain-like texture. When she was done I pulled my pants back up and left.

There’s a lot to dive into here, but I think what really makes this dream is the final sentence. A crowd has assembled to ominously demand that our dreamer let someone interfere with his genitals. Everything is big: the huge vat, the huge swollen foreskin, the hugeness of China. Big things are important. Our dreamer resists it all the way, from the second the old woman invites him into her stall; he is a consistently unwilling participant in his own dream. But then the terrible event happens and he just carries on. ‘I have no idea what to make of it,’ Brendan says. Me neither. The dream does contain a sequence of things that are eaten but which are not, strictly speaking, food: seed oils, Pringles, cum. But what does it mean to compare a penis to a brain? Crackpot interpretations welcomed.

1. If you die in the dream you die in real life

Well, actually, if you die in a dream, you wake up.

You people seem to have been dying a lot. Maybe the kind of person who’d subscribe to me is particularly anxious or macabre; maybe everyone is like this. Many of you were dying in plane crashes: one anonymous reader over the African savannah, one over Ukraine, one over London ‘but it was clearly made of cardboard,’ and one in ‘a forested region I knew was on another planet.’ Two of you have died on board planes crashing into your childhood homes. Despite the fact that they’re far more deadly, you did not appear to be dying in road accidents: I got a few stories about cars, but none of them were fatal for the dreamer. Death has a shape, and it looks like commercial air travel.

Aside from plane crashes, other mass-casualty events predominate. Nuclear war, tidal waves; the dream is a disaster zone. Last month I collected some disaster-dreams from my friends, and mentioned one who died when another planet collided with the Earth; I heard from several more of you that you’d had dreams of a similar nature. Among the comet impacts there was one I particularly liked, from Georgie:

I also dreamed about a meteorite, but in my dream Earth was being ‘chased’ by the meteor, so sometimes it was bigger in the sky and sometimes we could outrun it. My husband and I were on vacation in a beach hut on a tropical island with shimmering, lightly iridescent waters, a bit like an oil slick but all in various shades of baby blue. You could wade out for miles and the water wouldn’t come up further than your knees. As part of the global effort to outrun the comet we had to sprint through the surf every morning, but I kept stopping to look down at all the beautiful multicoloured fish and coral reefs, and every time the comet was getting bigger. My husband was grabbing my wrist, telling me to keep running, because ‘the fish will survive either way,’ but the fish were dancing provocatively around my feet and whispering ‘look at me, look at me, look what I can do.’ They told me they had a gift for me, and when I stopped the comet caught up with us and we died.

What does all this mean? According to a website called DreamChrist, ‘when you dream about meteors and the end of the world, this is a sign that you will face a lot of success due to your hard work. You are moving towards a new beginning and leaving the past behind.’ This seems tenuous. According to another website called DreamBible, ‘to dream of an asteroid coming towards the earth represents a potential problem.’ This is more plausible, but it’s not exactly a novel insight. DreamGlossary, meanwhile, suggests that ‘if you are dreaming of a meteorite hitting you, it means you will fall in love.’ Can we do better? David suggests that these dreams might be a product of your media diet:

As part of my job, I am required to log in to different corporate Twitter accounts, and am always struck by the different worlds that are presented to me. In my personal account, I am presented with memes, puns and cum jokes. On corporate/academic Twitter I am in a different universe. Threads from Serious Epidemiologists about how COVID is coming back to kill us all this December. Suggested news stories in the sidebar inform me it is also too late to stop climate change, 70% of animal species are already dead, and Putin plans to nuke us into oblivion any second now. Is it any wonder, then, that one of my colleagues, who lives only in the latter online universe, told me she dreams of nuclear apocalypse regularly? Of great tsunamis washing us all away?

But while these dreams look like fear, and the liberal-neurotic dreamer might interpret them as fear, I’m not so sure.

In Bruno Schulz’s short story The Comet, the asteroid impact isn’t just something that comes to annihilate humanity; it’s the crowning achievement of ‘the age of electricity and mechanics and a whole swarm of inventions.’ This is ‘the most progressive, freethinking end of the world imaginable, in line with the spirit of the times.’ But eventually the comet becomes just slightly passé—’fashion overtook by a nose and outstripped the indefatigable bolide’—and instead of colliding, the now-unhip comet simply roars through the sky and off again into space. Everyone is incredibly disappointed: now they are condemned to live. In dreams, too, these mass deaths can be shot through with desire. My friend Nina Power dreamed that she was killed in a nuclear apocalypse with all her ex-boyfriends. She still has warm feelings for these people, and the experience felt oddly peaceful, the atomic bombs burning like a beautiful sunset. Death comes like the end of a good relationship or the end of a good day. A gentle, grateful fiery end of the world.

Maybe we need Blanchot. ‘The disaster is the time when one can no longer—by desire, ruse, or violence—risk the life which one seeks, through this risk, to prolong. It is the time when the negative falls silent and when in place of men comes the infinite calm which does not embody itself or make itself intelligible.’

Other than that, there was no particular pattern to the ways in which you’ve been dying. One anonymous reader died when ‘a bunch of holes started opening up on the sidewalk. They were like the pits in Super Mario, full of spikes, and all the children on the street were jumping into them, so I thought I may as well follow them.’ Another saw fit to send this email:

Call me Matt. I was out hiking and got crushed to death by a herd of reindeer coming like an avalanche down the hillside. Woke up feeling weirdly great? Love the stack.

Speaking of animals, Jessica reports the following dream, which reads like something out of Kafka:

An unusually vivid dream last week where I was in a cattle stockade in 1920s Chicago. (I’m Irish, and have never been to the US.) I was trapped in there with hundreds of angry bulls; on one side workers were leading the cattle one by one into an abattoir, but before they could go in there was a judge who had to pass a sentence of death on each bull for their various crimes. (Mostly murder and blasphemy.) When it was my turn they made me stand on the conveyor belt and I kept protesting my innocence, but the judge just looked bored. He told me I could appeal the decision later if I wanted. Then the conveyor belt carried me into the dark doorway to be slaughtered and I woke up.

My girlfriend dreamed she was being euthanised by David Lynch in an ice rink. He was very gentle about it, administering the lethal objection, and it was far too late for her to register any objections. As she slipped into death everything faded to black, and then she woke up.

Why do we wake up after dying in a dream? As far as I can tell, the scientific hypothesis is that imagining yourself dying is a stressful experience, stressful experiences cause the release of adrenaline, and adrenaline wakes you up. I do not believe this for a second. Firstly, because not all of the dreams about dying you’ve sent in seem to be particularly stressful. Secondly, because among those dreams that are unpleasant, the most stressful moment often comes before the actual moment of death, when you realise there’s no escape—but you only wake up once you’ve actually died. Thirdly, because if stress alone could wake you up, nobody would ever have nightmares.

So much for neuroscience. I think psychoanalysis might have the germ of a better answer.

‘In analysis,’ Freud tells us, ‘we never discover a ‘no’ in the unconscious.’ The world of the unconscious is brighter and clearer than the world of the waking mind; everything that exists there exists fully, is simply present. As it happens, you can see this very easily in dreams: Matthew Spellberg, who I mentioned last time, points out that in a dream there is ‘no contemplation at a distance;’ as soon as you conceive of something, it’s immediately there. You can’ have a dream in which you’re thinking about a sandwich without the sandwich itself becoming perceptible. You certainly can’t have a dream about the absence of a sandwich. ‘Thoughts are experienced as reality.’ Because the unconscious does not know negation, everything repressed by the conscious mind ends up down there, where nothing ever vanishes. The whole work of analysis consists of dredging stuff up from the unconscious and into the open air where it can be taken apart.

But death is a special case. Death can never be subjectively there: it’s a huge inconceivable negation that can only be contemplated at a distance, since in its actual presence you yourself simply vanish. Freud again: ‘No one believes in his own death, or, to put the same thing in another way, in the unconscious every one of us is convinced of his own immortality.’ Death cannot be represented in the unconscious. This is why Julia Kristeva writes that the death drive does not, properly speaking, exist: there is only a ‘hiatus, blank, or spacing’ that gives cadence to the unconscious and its contents.

For Freud, dreams are first and foremost ‘the guardians of sleep and not its disturbers,’ and this is why every dream is also the expression of a desire. If there’s something you want, it’s presented to you in your dreams, so that instead of getting up and doing things you stay blissfully asleep. But when dreams have to represent death, which they are incapable of representing, they run into a contradiction. The whole system shuts down, like a calculator when you try to divide by zero. The dream stops working, sleep is left unguarded, and you wake up.

But we don’t always wake up immediately after dying in a dream. Last time, I wrote about a dream in which I died, but then had to carry on:

Once I was in a plane crash near the house where I grew up. Afterwards, I had to phone my mum and get her to pick me up in her car. She was very disappointed in me for having died. ‘We never thought you’d be the type to do that sort of thing.’ I lit a cigarette, and she told me she didn’t like me smoking. ‘Well,’ I said, ‘it hardly matters now.’

None of you experienced anything similar, but I did get one response that talked about a kind of interregnum between dying in a dream and waking up:

I’ve also died in a dream without waking up. Earlier this year I had a dream in which I was at my son’s friend’s birthday party (he’s four). They were playing a game called Poison Cup; I drank from the poison cup and keeled over immediately. I wasn’t remotely surprised; I just thought, well, I’ve died, but I’m still here, so obviously that was a dream. I’m pretty sure I was thinking consciously but I couldn’t wake up. I don’t think it was sleep paralysis exactly, I wasn’t in my bed, but I also didn’t have any auditory or visual hallucinations. It wasn’t even like my field of vision went black, there were no sensory inputs at all. I was just… nowhere. This lasted for about ten minutes, in which I was mostly convinced I’d been dreaming but still partway open to the idea that I’d actually died and this is what it’s like afterwards, just a consciousness alone in the void. When I woke up fully I didn’t even remember the dream at first, but then I was checking the news on my phone about Ukraine and I told my wife ‘oh yeah, I forgot I was dead.’ She was a bit freaked out.

Maybe the most fascinating story I received, though, was from an anonymous reader who actually went through a near death experience: