There are two named individuals known to live at the North Pole.

The first is Baxbakwalanuxsiwae, He-Who-First-Ate-Man-At-The-North-End-Of-The-World. In the mythology of the Kwakiutl people of what’s now British Colombia, Baxbakwalanuxsiwae is a primordial cannibal. His skin is grey, and every inch of it is covered in ravenous, gnashing, blood-stained mouths with razor-sharp yellow teeth. When those mouths aren’t crushing human bones or tearing human flesh, they cry hāp! hāp! hāp! which means eat! eat! eat! He goes naked in the snow. He lives in a lodge at the furthest northern edge of the world, with blood-red smoke rising from its chimney. He shares this lodge with his wife, Qominaga, who dresses in strips of red-and-white cedar bark; the two of them sometimes take the form of monstrous black birds and fly south to steal people away and eat them. Aside from Qominaga, he has servants at his distant home, who all take the form of monstrous black birds more or less permanently. One is a terrible raven: when Baxbakwalanuxsiwae has finished eating a man, he will throw the carcass out of his lodge and the raven will peck out and consume the eyes. Another has a long neck and a sharp, stabbing beak: he smashes the victim’s skull and feasts on his brains. Baxbakwalanuxsiwae dances and sings, but all his songs contain only one word: hāp; eat. The Kwakiutl would imitate him in the hamatsa or cannibal dance during the Winter Ceremony, recounting the story of four brave hunters who visited Baxbakwalanuxsiwae to acquire his terrible magic. They hid in the gloom of the monster’s lodge as Baxbakwalanuxsiwae danced and thundered, but one of them dared to peek out at his dance, and the great cannibal spotted him. Three of the brothers were devoured; one made it home with the magical powers, but also with an insatiable hunger for human flesh. The hamatsa was part of a young man’s initiation into Kwakiutl society, and it would be performed with something like holy terror: the great cannibal was the most powerful and the most feared being in their cosmology. Another translation of his name is Ever-More-Perfect-Manifestation-Of-The-Essence-of-Humanity. You are not different from the man-eater who lives at the North Pole and whose body is covered in wailing mouths. He was there long before you. He is your ancestor, and you are just a lesser, weaker, corrupted version of him.

The second inhabitant of the Pole is called Santa Claus.

1. Who is Santa Claus?

According to the conventional account, Santa Claus descends from a (probably) real historical person: Saint Nicholas, Defender of Orthodoxy, Wonderworker, Holy Hierarch, and Bishop of Myra, who (probably) lived in Asia Minor in the third and fourth centuries AD. The Golden Legend of Jacobus de Voragine describes his life in some detail, almost all of which is almost certainly made up. Nicholas, he writes, was so pious and temperate that even as an infant he refused the breast except on Wednesdays and Fridays, but when it came to others he was generous. During a famine, he performed a miracle: when ships from Alexandria stopped by the port, he convinced their captains to unload their wheat, but when the ships arrived at Rome the imperial inspectors didn’t find a single grain missing. Another time, he learned that his neighbour had fallen on such dire straits that he was planning to sell his three daughters into prostitution, so he conjured a lump of gold and threw it through his neighbour’s window. The next day, the neighbour thanked God for this miraculous dowry and found a respectable marriage for his eldest daughter. That night, Nicholas threw a lump of gold twice the size of the previous one, and the next day the neighbour thanked God even more effusively and found an excellent husband for his second daughter. That night, Nicholas threw a lump of gold that was twice as large again, but this time the clatter of the huge clod of metal was so loud that it woke up the neighbour, who chased after Nicholas, desperate to thank his benefactor. Eventually, he caught up with him. Nicholas allowed the neighbour to kiss his feet, in exchange for the promise that he would never reveal what had happened as long as he lived.

There’s an obvious problem here. If the neighbour kept his promise—and Nicholas isn’t much of a saint if he can’t even get people to keep their promises—then how did we end up with the story? Paradox of the hidden gift-giver, who everyone knows but nobody sees.

There are other stories. St Nicholas had a habit of resurrecting dead children by making the sign of the cross over them, including three boys who an evil butcher had killed and was pickling in a barrel of salt to be sold as ham. He defended the Jews of Myra against their persecutors, and afterwards the Jews were so thankful to the bishop that they accepted baptism and stopped being Jews altogether. There’s a tradition in which he was present at the First Council of Nicaea in 325: according to the story, Arius was expounding his doctrine that the Son is not coeternal with the Father but proceeded from him before the beginning of time (which—speaking as a basically agnostic Jew with no real skin in the game—does seem to make more sense), and this enraged Nicholas so much that he walked over and punched the heresiarch in the face. This story is also almost certainly untrue: Nicholas might have attended the Council (that is, if he did, in fact, exist), but Arius did not, and the fight isn’t mentioned in any sources for nearly a thousand years after it supposedly took place.

But a lot of things kept happening to Nicholas even after he died. His (purported) bones, for instance, were stolen from the church in Myra by Italians in the eleventh century and brought to Bari, supposedly to protect them from the Turks. (A lot of holy relics were ending up in Italy around that time. An entire house, supposedly belonging to the Virgin Mary, was miraculously removed from the city of Nazareth just as the last Crusaders were departing the Levant, and flown through the air by a team of angels to Loreto.) Nicholas was adopted as the patron saint of sailors, archers, brewers, coopers, pawnbrokers, Russia, and wolves. Because he kept being depicted with the boys in the barrel of salt, he ended up becoming the patron saint of children mostly by accident. And he was associated with gifts: especially in Germany and the Low Countries, people would exchange tokens on his saint’s day, December 6th. The Reformation ended up moving that date to Christmas, and Luther managed to convince the Germans to tell their children that their presents came from the Christ-child, not a long-dead Greek bishop. But St Nicholas hung on among the Dutch.

Sinterklaas is a jolly old man with a big white beard dressed in heavy red robes, who gives out gifts to children on Christmas. He is also, very visibly, a member of the Catholic clergy. He wears a mitre and a velvet chasuble and a ruby ring, all decorated with golden crosses. Traditionally, he comes every year to the Low Countries from Spain with a cargo of oranges. He also has a Moorish servant, Zwarte Piet, or ‘Black Peter,’ usually played by a white Dutch person in blackface with big red painted lips. Zwarte Piet has, unsuprisingly, become a bit controversial. An appreciable chunk of the Dutch population continues to insist that he’s not at all racist, but a much-beloved tradition and actually in a way a celebration of African people; even so, these days he’s increasingly being phased out for Roetveegpiet, or ‘Sooty Peter,’ who’s still in what you could call blackface but at least it’s not covering the entire face. Life is all about compromise. Maybe it’s enough that Zwarte Piet has now totally overshadowed his master; the controversy is basically the only reason anyone outside the Netherlands has heard of Sinterklaas. But really, the whole thing is deeply weird. These traditions were solidified in the sixteenth century, just as the Dutch were fighting the Eighty Years’ War against the Habsburg monarchy in Spain. In the Dutch Republic that followed, all overt Catholic worship was forbidden: priests had to hide in attics, wearing ecclesiastical finery recycled from ladies’ gowns, while the Calvinist ministers stalked the streets in austere black. But then at Christmas, suddenly the Dutch would cheerfully parade a Spanish Catholic bishop in all his idolatrous adornment through their streets.

Eventually, all this was resolved in the New World. Dutch settlers took Sinterklaas with them to their colony of Nieuw Amsterdam, and the tradition survived even once the factory was captured by the English in 1664 and renamed New York. But the English-speaking colonists stripped Sinterklaas of his overt Popery, and identified him with the already-existing English figure of Father Christmas. (Originally, Father Christmas had nothing to do with gift-giving; he was just a vaguely cheerful man in a big green coat. Once, the imagination produced whole hosts of these ambulatory concepts. Muses, virtues, days of the week, seasons of the year, fields of study, emotions. Almost none survive. A few national figures, like Marianne and Uncle Sam, plus Christmas, and the Baby New Year that becomes a withered old man in twelve months’ time.) And so Santa Claus was born. For a while he was just a local tradition, mostly confined to New York, but the presence of an excellent natural harbour and the steady growth of American manufacturing power soon meant that the local traditions of New York became the local traditions of the entire planet. Santa has swallowed up all his ancestors and competitors. Father Christmas is Santa with another name now, and St Nicholas of Myra is just a weird piece of Santa trivia. Unlike his creepy prototype, Santa doesn’t drag the pale, lifeless bodies of three children out of a barrel of salt. He doesn’t represent any particular belief regarding the coeternity of the persons of the Trinity. What he represents is belief itself. Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus. In America, all the great battles have already been won; the long European tragedy, its mythic and ideological conflict, its wars of religion, have all been turned into a slightly condescending game for children. A country that doesn’t believe in anything, except its own mawkish, billowy belief. Nicholas the Defender of Orthodoxy has become the presiding deity of the great American kayfabe, where you pretend—not for yourself, of course, you know the truth, but for the others—that commodities can appear like magic in the middle of the night. (The kids too. Kids always secretly know.) A lot of people seem to think that he was invented, whole cloth, by the Coca-Cola Company. They may as well be right.

Anyway, that’s the conventional account. Did you believe it?

I’m not so sure. Something’s off about this story. The Santa Claus we’ve ended up with is a weird guy, and there are a lot of things about him that seem to have no obvious precedent in the Anglo-Dutch tradition. For instance: his practice of going into houses via the chimney. Why? Or his team of flying reindeer. Or Mrs Claus, who is not the sort of companion a Catholic bishop ought to have. Or that Ho-Ho-Ho. Most of all, though, there’s his choice of home. Sinterklaas comes from Spain; Father Christmas comes from Lapland. But Santa lives at the North Pole. A barren, freezing wilderness, impossibly distant from all human civilisation, where nothing lives and nothing grows. No mountains or valleys. No soil. Just ice, miles of ice creaking over the abyss. And darkness, months and months of bitter darkness that doesn’t break until spring. A place pitiless beyond imagining, where Santa’s only neighbour is Baxbakwalanuxsiwae of the chomping mouths.

Why?

2. What is the North Pole?

There are, in fact, two North Poles. The terrestrial pole is the expanse of featureless ice at the point where the Earth’s axis intersects with its surface, and as far as we know, it wasn’t seen by human eyes until the twentieth century. But the celestial pole can be seen from anywhere in the northern hemisphere. It’s the point in the sky aligned with the Earth’s axis: the one star that does not move. There’s an invisible line connecting the ice caps where the wind screams at night to the star Alpha Ursae Minoris, four hundred light years away. The entire universe rotates around that line. Along the length of the line itself, everything is still. All this can be worked out purely by observing the heavens: the existence of the celestial pole implies, somewhere in the unreachable north, a terrestrial one. Somewhere, across the seas, lies the only point on the Earth’s surface that’s in direct contact with the harmony of the spheres.

If you’d only seen the celestial pole, why would you think that the terrestrial pole would be barren? It makes far more sense to imagine a garden, some kind of earthly paradise. The Greeks called that place Hyperborea. The north is cold because of the Boreas, the terrible freezing wind coming off the high mountains at the north end of the world. But on the other side of those mountains, right at the pole, there’s the land of permanent spring. In the sixth century BC, Hecataeus of Miletus described that land: ‘both fertile and productive of every crop, and since it has an unusually temperate climate it produces two harvests each year.’ The Hyperboreans are tall, up to ten feet tall. Their skin glows. They live for hundreds of years, without war, without disease, and without hard labour. Both men and women cut their hair short, and their land is full of lush forests, hidden temples, streams populated by pure white swans. The ancients understood the axial tilt; Pliny records a tradition that here, at the site of ‘the hinges upon which the world revolves, and the extreme limits of the revolutions of the stars,’ the Hyperboreans experience ‘light for six months together, given by the sun in one continuous day.’ Other astronomical anecdotes are weirder. According to Diodorus Siculus, ‘the Moon, as viewed from this island appears to be but a little distance from the Earth.’ Once every nineteen years, the Moon passes so close to Hyperborea that it’s possible to leap across the gap and walk on its surface.

The Hyperboreans are gift-givers. In his Histories, Herodotus writes that the Hyperboreans once sent two beautiful maidens named Laodice and Hyperoche with rich offerings for all the temples of Greece. Poor gentle creatures: in their arctic paradise, they didn’t understand the cruelties of the world where Boreas blows. Somewhere along their pilgrimage—Herodotus doesn’t say where—Laodice and Hyperoche were raped and murdered. In their grief, the Hyperboreans closed themselves off from the rest of the world. They still send their offerings, but they only venture so far. Gifts wrapped in straw are given to the one-eyed Arimaspians, who pass them on to the savage Issedones of far Asia, who pass them on to the blood-drinking Scythians on the northern steppes of the Black Sea, who send them on to the Greeks. Hyperborean goods circulate in all the markets of the Aegean. You bought your gifts from a perfectly ordinary seller, but really they come from the magical land at the North Pole.

Christianity killed off Hyperborea for a while; the navel of the world was now firmly placed elsewhere, at Jerusalem. The North Pole is not a particularly interesting place for the moral drama of salvation. But it did suddenly become very interesting again once the compass reached Europe in the twelfth century. If you take a lodestone, poke it through a piece of cork, and float it in a bowl of water, it will spin until it points at the North Pole. What’s going on there?

The medieval world was aware of magnetism, even though it had no way of explaining it. (If this feels like a weird state of affairs, consider that you are also aware of magnetism, but—let’s be honest—you also have absolutely no idea how it actually works.) As late as the seventeenth century, the great Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher could explore the possibility of a global telecommunications system based on electromagnetism while also confidently asserting that magnets get weaker in the presence of garlic and onions but can be strengthened by immersion in the blood of a wild boar. But enough of the basics were understood to make the solution to the riddle of the compass obvious: there must be an enormous magnetic mountain at the North Pole.

What’s more, there was someone who claimed to have seen the magnetic mountain for himself. In the 1360s, a Franciscan monk from Oxford recorded his travels in the Arctic in a book called the Inventio Fortunata, which describes an immense black rock at the crown of the world, surrounded by an enormous whirlpool, which sucks in the world’s oceans through the narrow channels between the four arctic continents. The Pole sounds like a very harsh, very bleak place. There are no glowing, peaceful Hyperboreans. The only signs of human life are the splintered ships that veered too far north and were wrecked in the intense currents of the rushing channels. Unfortunately, no copies of the Inventio Fortunata survive; we only know about it because it was summarised in another book from the same era, the Itinerarium of one Jacobus Cnoyen. The Itinerarium, as it happens, is also lost. But it was itself summarised in one document we do have: the 1577 correspondence between the Flemish cartographer Gerardus Mercator (yes, that Mercator, the one who gave us the notoriously tropico-diminutive projection) and the wizard and mathematician John Dee (previously described in this space as ‘England’s greatest-ever weirdo’). Mercator writes that the lands near the Arctic Circle were subjugated a thousand years beforehand by King Arthur, who then sent an army of four thousand men sailing up through the terrible channels to the top of the Earth, of which none ever returned. Only the author of the Inventio Fortunata had looked on the Pole and lived. He reported ‘that right under the Pole there lies a bare rock in the midst of the Sea. Its circumference is almost 33 French miles, and it is all of magnetic stone. And is as high as the clouds… One can see all round it from the Sea: and it is black and glistening. And nothing grows thereon, for there is not so much as a handful of soil on it.’

Mercator’s maps of the Arctic show that mountain, marked Rupes nigra et altissima, or Black and very high rock. But only a few decades later, some thinkers were beginning to claim that there was no magnetic mountain at all: the secret of the Pole wasn’t on the surface of the Earth, but beneath. In 1600, William Gilbert proposed that the entire Earth was one enormous magnet, a sphere of iron producing a magnetic field, and that its poles were just huger versions of the poles of any lodestone. He was completely right. (He also argued that this magnetic field powered the Earth’s rotation on its axis, along with the orbit of the Moon. You can see why this would have made sense at the time.) But Athanasius Kircher, who we’ve already met, pointed out that the magnetic pole and the axial pole did seem to occupy slightly different positions on the Earth’s surface. What’s more, the magnetic field was stronger in some parts of the world than in others. Why would this be? If we were living on the surface of a single spherical magnet, shouldn’t its effects be evenly distributed everywhere? Kircher’s explanation was that there were fibrae magneticae, filaments of lodestone, running haphazardly through the centre of the Earth from one pole to the other. But these filaments were only one of the treasures of the subterranean world.

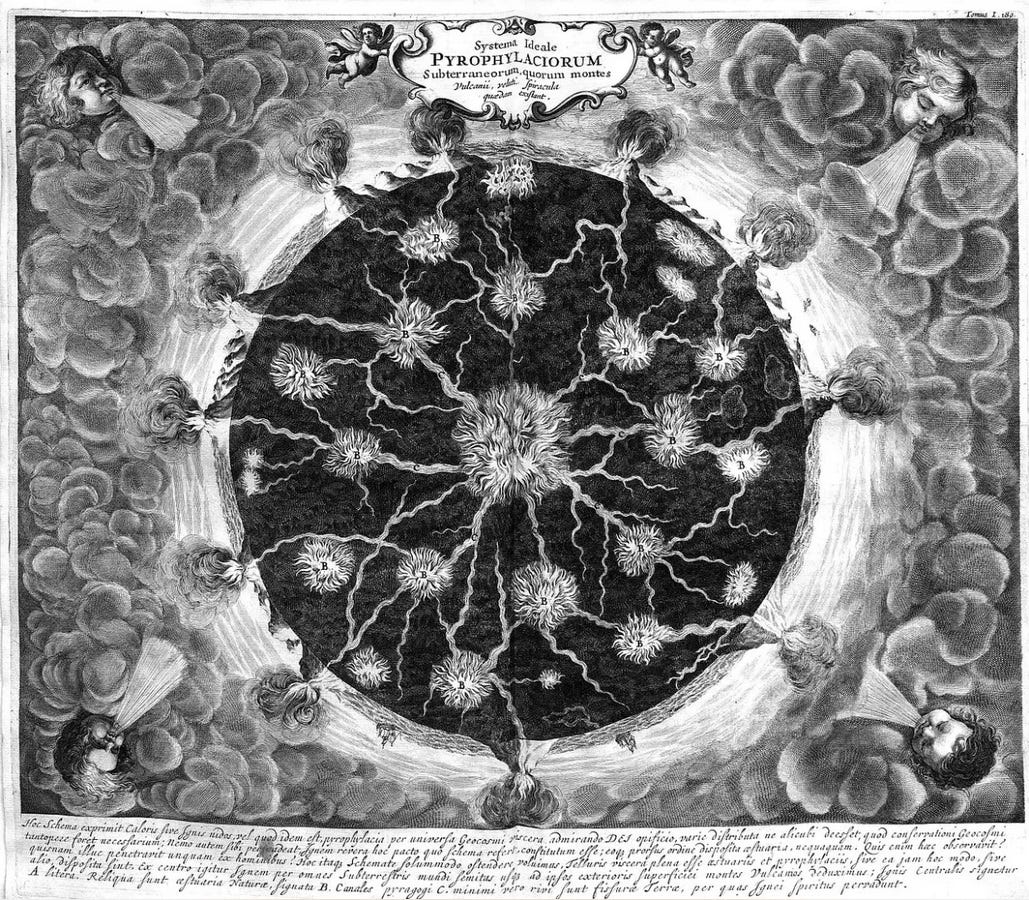

In 1638, Kircher had witnessed an eruption of Mount Stromboli that killed some ten thousand people. In the aftermath, he climbed Vesuvius: he wanted to understand how volcanoes worked. After making it to the peak, he peered into the crater. ‘I thought I beheld the habitation of Hell,’ he wrote: a place of ‘horrible bellowings and roarings.’ Still, he descended, into the interior of the mountain, until he found a pool ‘boiling with an everlasting gushing forth, and streaming of smoke and flames.’ He came away with the sudden insight that there are enormous reservoirs of fire beneath the Earth’s surface. Not just fire either. He reasoned that there must also be underground oceans too, which would explain where the water went at low tide: a network of caverns and channels extending all the way to the core of our world, connecting everything we see in hidden tendrils underground. In 1665, he produced his masterwork, the two-volume Mundus subterraneus, quo universae denique naturae divitiae: a vast encyclopaedia of the hidden world, featuring chapters on the people who live their entire lives beneath the surface, the dragons that inhabit the Earth’s core, the location of Atlantis, the alchemical operation of seeds, and the tellurian origin of all poisonous snakes. ‘The whole Earth is not solid,’ he explains, ‘but everywhere gaping, and hollowed with empty rooms and spaces, and hidden burrows.’

In case it wasn’t clear, I love Athanasius Kircher. I don’t think any man has ever been more impressively wrong about so many things. He believed that he’d finally translated the Egyptian hieroglyphics but had not; he thought that Chinese culture encoded a half-forgotten knowledge of Christ that it did not; he conjured a wonderful subterranean world that does not exist. It takes a genuine genius to encompass so many spheres in your idiosyncrasy. He was wrong about fossils and mountains and animal speciation and the movement of the Earth, but all his wrong ideas make perfect sense, and all of them are beautiful. None of Kircher’s errors were free of true and brilliant insight. He wasn’t just the first to realise that the world is molten beneath our feet; he went further, and through a series of entirely reasonable inferences he invented a entire secret and magical world.

For a long time, though, the hollow Earth seemed as good an interpretation as any. Edmond Halley, who recorded the transit of Mercury and computed the orbit of his eponymous comet, suggested that the Earth might be a hollow shell, with another Earth nestled inside it, and another beneath that. These other Earths would have their own glowing atmospheres, their own nonsynchronous rotations, maybe men and women living down there, maybe whole kingdoms. They would also have their own magnetic fields: this was how Halley accounted for the constant shifts and irregularities in the geomagnetic readings. It was the other Earths, moving invisibly around. But it took an enterprising American, John Cleves Symmes Jr, to see the obvious next step. What if there were a hole in the world? Such a hole could only exist at the Pole, the only point on Earth that doesn’t rotate. Symmes calculated that if our eggshell of an Earth were around one thousand miles thick, and the lip of the hole were smooth enough, you could actually walk through the hole and continue along the inside surface of our hollow Earth without ever actually noticing. The Arctic would be the gateway to an entire new world to conquer and settle. Symmes sent pamphlets explaining his theory to universities across America and foreign governments across the world, each alongside a certificate confirming his sanity. He spent his entire life on the lecture circuit, trying to raise funds for an expedition to reach the Pole and explore the hidden world within. No such expedition took place in his lifetime. He died in 1829, in massive debt.

There’s something very American about Symmes’ project to colonise the interior of the Earth. Being miserable, Europeans took things in the other direction. The point isn’t for us to go in; the point is that maybe this is where we came out. Suddenly, in the waning years of the nineteenth century, people started talking about Hyperborea again. In Helena Blavatsky’s Secret Doctrine, the first humans to exist were disembodied aetherial spirits who reproduced by splitting like amoebas and lived directly on the North Pole. In 1926, Roald Amundsen flew directly over the North Pole and confirmed that there was no Symmes hole, no celestial doorway, absolutely nothing except ice, but that didn’t seem to dampen anyone’s enthusiasm. The esotericist René Guenon called the inner surface Agartha, which is the secret home of the King of the World. ‘The time will come when the peoples of Agarthi will come up from their subterranean caverns to the surface of the Earth.’ (A lot of this occult doctrine is borrowed from The Coming Race, an 1871 science-fiction novel by Edward Bulwer-Lytton, best known for starting another of his books with the line ‘It was a dark and stormy night.’) Guenon also wrote that Hyperborea was the birthplace of the human race, ‘the first and supreme centre for the whole of the current Manvantara, the archetypal sacred island, and its situation was literally polar at the origin.’ Increasingly, you start encountering the notion that some people entered the world through the cosmic gate at the North Pole, and others did not. Something about that heavy coat of ice: cold, white, constant, pure. Close to the stars. According to Julius Evola, ‘the Hyperborean race could be considered, among all of them, the superior one, the super-race, the Olympic race reflecting in its extreme purity the very race of the spirit.’

You know what’s coming next. Entire cities burning in the night. Thousands of people marched in front of ditches and shot. Extermination camps. The starved, skeletal, dying, in the most cultred and civilised country on Earth. The whole of Europe, from the Atlantic to the gates of Moscow, blasted into ruins.

The Nazi Party began as the political wing of the Thule Society, an esoteric group devoted to the doctrine that the Aryan race had its origin in the Arctic. It’s a bit dicey to make too much of this sort of fact: if you assimilate the evils of Nazism to pure unreason, the implication is that as long as we don’t believe in anything crazy about the ice caps we have noting to fear; this might be why there’s so much scholarship exploring how fascism was, in practice, directly governed by the ordinary logic of capital. But the fact remains: the Nazi Party began as the political wing of the Thule Society. Initially, a few Nazis held to a very bizarre version of the Hollow Earth theory, in which we’re already on the concave surface. We live on the inner surface of a bubble, surrounded by infinite solid rock; the Sun and Moon float somewhere in the middle, and the stars are just points of light thrown up by the luminous inner atmosphere. If there is a hole at the North Pole, it doesn’t lead down, but up and out: here you exit the universe entirely, and ascend into the bright world of the Hyperboreans. This would also mean that you see across the world just by looking up. In 1942, a unit of the Kriegsmarine put the theory to use by setting up an infrared imaging array on the Baltic island of Rügen and pointing it into the sky at a forty-five degree angle, hoping to spy on British naval manoeuvres across the negative curvature of the Earth. Unsurprisingly, they failed to spot any warships in the sky. Afterwards senior Nazis, including Hitler and Himmler, adopted the Welteislehre or World Ice Theory instead, which held that the universe is made of ice, the stars are glinting shards of ice, the moon is made of ice, and human beings and our cultures are ultimately made of ice too.

They’re difficult for me, these Nazi theories. I see something beautiful in Kircher’s hidden caverns of fire, and I can also see something beautiful in the universe made of infinite rock or the universe made of infinite ice. The difference is that Peter Bender, great evangelist of the Hohlweltlehre, advocated for his concave Earth on the grounds that ‘an infinite universe is a Jewish abstraction,’ while ‘a finite, rounded universe is a thoroughly Aryan conception.’ The German leadership didn’t embrace these ideas because they were wonderful; they embraced them out of a refusal to admit that the actual workings of the universe were being teased out by men with names like Franck and Levi and Einstein. What’s really notable about these theories is how half-arsed they are, how limply they were believed. People who weren’t really interested in caverns of stone or galaxies of snowflakes: just the nation, the race, the group, the enemy. Pathetic stuff. Some weird wind drives these beliefs with no believers to the Pole.

But the reality is, when you think about it for a moment, also magnificently strange. Human life did not begin at the Pole; it does not contain the entrance to the hidden subterranean world; there are no lush forests or flocks of white swans. But it does contain, among its empty plains of ice, the surging nexus of an intangible energetic field produced by the roiling of molten iron at the centre of the Earth, that coils around our entire planet and prevents the air we breathe from being stripped away and dragged deep into outer space by the terrible radiance of the Sun, and that is visible in the sky as a luminescent circumpolar ring of solar ions burning red and green. A Christmas bauble, planet-sized.

3. Seriously, who is Santa Claus?

There’s one more weird quirk in the story of the Pole. In the sixteenth century, European geographers believed in an enormous whirlpool at the North Pole, draining the world’s oceans into the centre of the Earth. We now know that it isn’t there. But strangely enough, we find pretty much the exact same account on the other side of the world, among none other than the Kwakiutl. The Kwakiutl have two names for the North Pole: one means North-End-Of-The-World, the other means Mouth-Of-The-River. The Kwakiutl conceived of the Pacific Ocean as an enormous river flowing north, and emptying, at its mouth, into the void where Baxbakwalanuxsiwae has his lodge. This is a very unusual model: while both Europeans and Americans have imagined the sea as a river, it’s almost always a circular, eternal river, with no source and no mouth. The most likely explanation is that this is pure coincidence. But let me indulge in a bit of deranged pseudohistorical speculation. Could the Kwakiutl have picked up this account from the Europeans? Maybe, although first contact between Europeans and Kwakiutl didn’t take place until the end of the eighteenth century, by which point the Rupes nigra was entirely discredited. But what if the cultural transmission went the other way?

Remember that our only source for this vortex is the lost Inventio Fortunata, whose author is entirely unknown. We’re told that he was an English friar. I want to sketch out an alternative. In the fourteenth century, just as the Inventio Fortunata was supposedly composed, the Inuit culture was rapidly spreading westward from the area around the Bering Strait across the Hudson Bay to Greenland and beyond. Some time later, records from Orkney and Faroe describe the arrival of strange newcomers fishing the northern waters in boats ‘made of seal skins or some kind of leather.’ One observer noted that when these strangers were facing a particularly nasty wave, they would capsize their boats and hang upside-down beneath the water before righting them again once the wave had passed. These were Inuit kayaks; their boat-spinning technique was an Eskimo roll. This was in the seventeenth century, but it’s not impossible that some Inuit kayakers might have made the journey to Europe long before. If there was contact in the Middle Ages, one obvious topic of conversation would be the geography of the northern waters. Mercator’s Arctic, with its landmasses divided by rushing channels, doesn’t partcularly resemble the actual ice cap—but it does look a lot like the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, which the Inuit had conquered. The Inuit traded with Siberians across the Bering Strait, and they were plugged in to the communications networks that spread down the West Coast of North America. It has a lot of moving parts, but there’s a mechanism by which Kwakiutl ideas could have filtered through to medieval Europe.

Incidentally, the Orcadians identified the visiting Inuit as ‘Finn-men,’ by which they meant Sámi, Laplanders, who sometimes fished in small canoes. Lapland is, of course, the traditional home of Father Christmas.

Anyway, if the name Kwakiutl has been ringing a bell, it’s because they also happen to be one of the canonical ethnographic societies. Franz Boas, the father of American anthropology, repeatedly visited the Kwakiutl in their chilly settlements between 1885 and 1930. He witnessed their dances and ceremonies and noted down important details about their arctic cannibals, but what really struck him was the potlatch. During the winter ritual season, Kwakiutl nobles (they had an extremely rigid formal class system) would engage in feats of competitive gift-giving. This was the basis of the entire Kwakiutl economy, and also most of their political system. Here’s how he describes it: ‘Possession of wealth is considered honourable, and it is the endeavour of each Indian to acquire a fortune. But it is not as much the possession of wealth as the ability to give great festivals which makes wealth a desireable object to the Indian. The man’s name acquires greater weight in the councils of the tribe and greater renown among the whole people as he is able to distribute more and more property.’ Sometimes, most notoriously, people would compete to destroy their own possessions. This could take the form of a grease feast, which the host would begin by setting his own house on fire. Boas: ‘The flames leap up to the roof and the guests are almost scorched by the heat. Still the etiquette demands that they do not stir, else the host’s fire has conquered them. Even when the roof begins to burn and the fire attacks the rafters, they are unconcerned.’ The host and his guests would then take turns to dump their stocks of salmon grease—which was crucial stuff, used to make lamps and insulate bodies against the cold winters—on the fire. Another prestige good consisted of copper plates: you would shatter one of your plates and hand the shards to your enemy, at which point he would either destroy one of his own, or, if he wanted to ramp up the rivalry, throw the pieces in the sea. The Kwakiutl also kept human chattel. At a particularly extravagant potlatch, they might feel the need to demonstrate their aristocratic disdain for wealth by massacring their own slaves.

Through the potlatch, the Kwakiutl—or, at least, a certain idea of the Kwakiutl—practically took over twentieth-century European thought. From Boas to Marcel Mauss, The Gift, to Georges Bataille, Guy Debord, Baudrillard, eventually Derrida. The youth on the streets in May 1968 spoke the language of Marx, but their heads were full of ethnography. Primitivism; the liberation of all desire from Western neuroses: even the desire to destroy. They didn’t want socialism, with its wholesome dutiful production of ordinary use-values; they wanted permanent potlatch. The splendid annihilation of the commodity. But capitalism is good at playing tricks on people, and it gave them something very close to what they wanted: the commodity as a form of annihilation. Or, as we call it, Christmas.

Look: I love Christmas. Being Jewish, I’ve never really associated it with gifts, but I love the lights, the cities glittering in the chill, the moment when the afternoon gloom is just slipping into night and everything turns into diamonds. I love the huge tacky displays outside people’s homes. I love to eat six mince pies a day, every day, from October until the end of the year. I love the enormous meal. Parsnips. Bread sauce. Brandy butter. Dark heaps of suet and fruit. Carols, bells. Small acts of kindness or indulgence: oh, go on; it is Christmas after all. I love the spirit that says, in the cold lean months when the earth is dead and the sky is always miserable, when there’s nothing to do except hold on until the Sun returns, that now is the time to be lavish and extravagant and feast. I love Wham! and I have learned to tolerate Mariah Carey. But when I catch a glimpse of that figure in red, knowing what I know, I get a chill.

I began by saying that there were two named individuals who live at the North Pole. This was a lie. In fact, I think there might only be one. As we’ve already seen, there’s a mechanism by which the cosmologies of Western modernity have secretly been influenced by Kwakiutl concepts. I think that somewhere in America, some time in the nineteenth century, this happened again. Santa Claus wears the skin of St Nicholas of Myra, but it’s only skin. He doesn’t come from the red coasts of Asia Minor; he comes from the iron-grey shores of the northwest, where decaying whalebones curve like fangs out of the froth. His real name is Baxbakwalanuxsiwae.

Consider:

Both Santa and Baxbakwalanuxsiwae live in a lodge at the North Pole.

Both are venerated in a ritual season around the winter solstice.

Both are associated with red and white clothing.

Both have a wife.

Both are attended by flying animals.

Both know when you’re peeking.

Both represent systems of deliberate, magnificent profligacy; rituals of antagonistic gift-giving that can be figured as a kind of cannibalism. (If gift-giving conveys a kind of social power, then Santa is the true king of the world. This might be why he has to live in an unassailable fortress at the Pole: you can try to give him cookies, but out there, you can never hope to compete with him; you can never give a gift back.)

Santa says Ho! Ho! Ho!—an obvious corruption of Baxbakwalanuxsiwae’s ravenous cry: Hāp! Hāp! Hāp!

Both enter your house through the chimney.

Fine—not exactly a chimney. But Kwakiutl ritual lodges did feature something called the cannibal pole, a forty-foot cedar mast projecting up through the roof of the house, usually carved with images of man-eating birds. I’ve already mentioned the hamatsa dance in the Winter Ceremony, which took place near the solstice: as part of the ritual, a young intitiate would be told to climb the cannibal pole. At the top, he would receive the fearsome spirit of Baxbakwalanuxsiwae, and return as a powerful and terrifying cannibal. Afterwards, he would have to live alone in the woods until his cannibal frenzy had dissipated. But as he descended the chimney, Santa Claus would chant:

I went all around the world to find food. I went all around the world to find human flesh. I went all around the world to find human heads. I went all around the world to find corpses.

And the people would chant in return:

You will be known all over the world; you will be known all over the world, as far as the edge of the world, you great one who safely returned from the spirits. You will be known all over the world; you will be known all over the world, as far as the edge of the world. You went to Baxbakwalanuxsiwae, and there you first ate dried human flesh. You were led to his cannibal pole in the place of honour in his house, and his house is our world. You were led to his cannibal pole, which is the Milky Way of our world.

This sudden lurch into cosmic imagery points to some deeper secret. Now Baxbakwalanuxsiwae’s house is the entire world. He springs forth at the Pole. He covers the globe in a single night. He encloses us. I can think of one terrifying possibility: that Santa is a magnetic demon; that this monster is a vision of the Earth’s magnetic field. What did the Kwakiutl know about the Earth’s magnetic field that we do not? Something about the constant geodynamic flow of molten-red iron beneath the Earth’s surface demands flows of red human blood above. Something about midwinter and magnetism is best represented as a cannibal with bloodstained jaws covering every inch of his body. Maybe there’s a sentience we have not yet dreamed of, made up of the electrical pulses that flash through billions of cubic miles of churning metal and up to the edge of outer space, rather than a few pounds of wobbling flesh. Maybe the magnetic field is chaotic and uneven because it is alive. This monster is billions of years old, eyeless, senseless, but he would know us: he can feel the electrical eddies of our thoughts. And since we’ve received the gift of his protection, he can choose to take, whenever he wishes, a few of our brief, buzzing lives. Maybe Santa possesses human bodies, blotting out their weaker brainwaves with his own. Or maybe he can build a body for himself. Maybe there are nights near the solstice when the solar wind roars against Santa’s planet-sized face, dense with charged particles, heavy ions blasted out of the burning Sun and channelled through the eddies of the magnetosphere to coagulate: nights when he can take his gruesome shape to float through the world above. Maybe he will visit your house tonight. You have spent your entire life in his.

Merry Christmas.