The brute brute heart of a brute like you

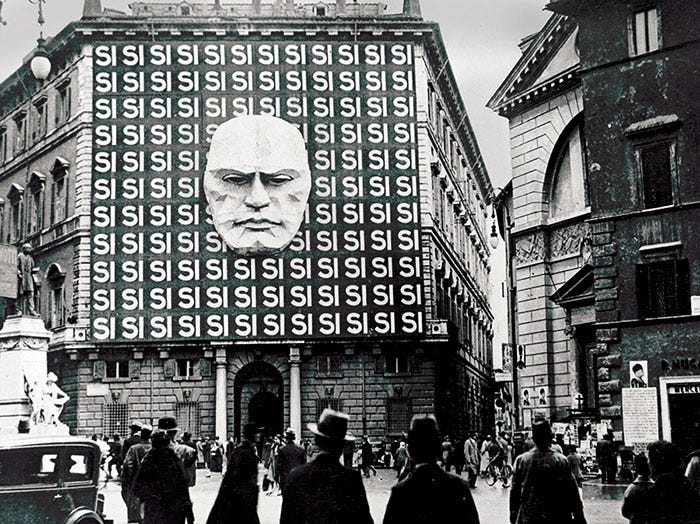

On fascism, and 'fascism'

It might not surprise you to learn that I have a master’s degree in critical theory. Eight years ago, I moved to Brighton to spend a year reading Adorno: to learn why slippers and light music and cheap restaurants and expensive cocktails are all actually fascism, coterminous with the death camps and the Final Solution. I guess it felt like a good idea at the time.

For much of that year, I was also completely broke. I got a job at a pub and managed to work a single shift before the owner discovered that his wife was cheating on him with his closest friend. His response was to have a psychotic break, fire us all, and sell the place to a property developer to be turned into flats. Sometimes I’d write a piece for Jacobin or The New Inquiry and make a hundred pounds or so; sometimes people would recognise me on campus as I stomped around like Raskalnikov, mortifying in my shabby old coat spotted with little beads of fuzz. At the time I had a few thousand Twitter followers and a blog; the University of Sussex campus was probably the only place on the planet where my name meant anything to anyone. One person told me that she’d had a one-night stand, and afterwards the guy had asked her if she’d ever read any Sam Kriss. This story was meant to be embarrassing for him, and her, and also for me. Look who likes you: the kind of loser I’d fuck. It was.

I stole food from the big Sainsbury’s off Lewes Road. I stole books from the big Waterstones in town. I was paying just under £400 a month to live in a damp, poky semi-detached house in Moulsecoomb, a mostly impoverished suburb that had been built on Brighton’s outlying swamplands in the early 1920s. That swamp was still lurking there, unseen, beneath the tarmac. It gave us the black mould that speckled the corners of our ceilings and the green slime that coated our windows from the inside. It bubbled out of the grass when it rained. Once, this had been a home fit for heroes to live in, but our landlord had different ideas. He’d converted the living and dining rooms into bedrooms, to cram in extra students. We ate off a rickety flatpack table in what had previously been the downstairs hallway, and which was also where we hung out our washing. There weren’t enough chairs. My own room was only accessible through a door in the kitchen, in a thrilling breach of all known fire regulations. I couldn’t afford to go out much, so I ended up sleeping with my housemates instead, which was also thrillingly forbidden until it turned out to be just another mistake. I think I must have been very unhappy.

When I needed to get to uni, I usually walked. A line of hills separated my hovel from the campus in Falmer; the quickest way there was to trudge up over its sodden crest and down again. From the very top you could just see the sea, a tiny mocking patch of glitter between the dull grey earth and the dull grey sky. It took about forty minutes; sometimes I’d stop to look for magic mushrooms growing in the cowshit. (Over the course of that year I found exactly one, which I boiled up into a tea and drank to no effect whatsoever.) If it was truly pissing down, though, I’d have to take my chances with the train. Moulsecoomb is one stop away from Falmer on the East Coastway Line, but the service had been franchised out to Govia, one of the firms founded in the 1990s to wring a profit out of our formerly nationalised railways, and they were fucking it up very badly. Their 7:29 service from Brighton to London, for instance, had arrived late every single morning for that entire year. Trains were often crammed and unreliable, and they also cost more than I could really afford, so when I did take one I would simply not pay. There were no ticket gates at Moulsecoomb, and at Falmer they were usually left open: I could just jump on the train and off at the next station, and spend my short journey having small neurotic dreams about what I would do if someone in a uniform ever asked to see my papers.

Obviously, this ended up happening. They always catch you in the end. One day I arrived at Falmer with my bag full of Freud and Hegel to find the ticket gates resolutely shut and a man in a blue pullover inspecting everyone’s documents by hand. Too late to turn around now. When my turn came, I pretended to search through my wallet, but oh no, my ticket wasn’t there, and how could this have happened? I suggested that if the man in the blue pullover let me through the gates, I could buy another ticket from the machines on the other side. I was practically pleading with him; I must have seemed very pathetic. He pretended not to understand me. If you’re travelling without a ticket, he explained, you have to pay a fine. That was all. No look I’m sorry mate but, no I’m afraid I’ll have to, not even an only doing my job. There was a horrible little smile buried in the corners of his mouth. Grim exultation, like a hunter who’d just brought down a fat prize. My fine came to over £200. I lived off rice and tomato paste until Christmas.

The rest of that day I spent in a foul and grudgeful mood, with most of my resentment focused on the figure of the man in the blue pullover. I don’t think I made much effort to consider that I had, in fact, been breaking the law. I didn’t consider that for society to function, pending the imminent workers’ utopia, people might have to pay for certain goods and services. I didn’t consider that I had grown up with more privilege than most, and that if I couldn’t afford a train fare it was because I’d chosen to spend my barmitzvah money on a postgraduate degree in the identity of identity and nonidentity. I was burning too hot for that sort of thought: this man was an image of everything I hated in the world. He had enjoyed it; he had enjoyed making my life worse as I begged him for some small shred of mercy. Our bad and unfree society hadn’t given him much power, but it had given him just enough to be cruel, and he had taken it. If I had been a different Jew, in a different time, on a different train, he would have herded me into the camps with the exact same look of neutral fastidiousness and the exact same secret pleasure. I knew exactly what to call this small, petty, hidebound nastiness. He was a fascist. I had come face to face with fascism.

I may have overreacted a little. But I still don’t think I was entirely wrong.