When Varius Avitus Bassianus was fourteen years old, the soldiers of the Third Legion threw a purple cloak over his shoulders and acclaimed him Emperor of Rome. Three years, nine months, and four days later, when Avitus was either seventeen or eighteen, the soldiers of the Praetorian Guard hacked him to death and threw his body in the Tiber. They killed his mother too, cut off her head, stripped her body, dragged it on hooks through the city, and threw it in a sewer. His friends and lovers were also killed. His name was erased from public inscriptions. His statues were recarved with the face of Alexander Severus, his successor. The Senate ordered that all coins struck in his image should be recalled and defaced, but the Empire was large and no two Emperors look all that different. Most local mints simply stamped a big A for Alexander over his portrait. Avitus’ name also begins with an A, and so does Antoninus, the name he adopted as Emperor, but apparently that didn’t matter. It was enough.

In those three years, nine months, and four days, Avitus had deeply upset the Romans. Our best contemporary source for his life is the Historia Romana of Cassius Dio, who devotes his final chapter to the brief reign of the teenage emperor. The book only survives in fragments, but there’s more than enough there. We learn that Avitus declared himself consul without having been elected, failed to wear the correct ceremonial dress on the Day of Vows, and had various people who opposed him killed. What Dio really gets into, though, is his sexuality. Avitus, he writes, had sex with men. Which would have been fine, if he weren’t the receiving partner. Even that might have been forgivable, if he’d had any tact about it. But according to Dio, he had no tact. ‘He would go to the taverns by night, wearing a wig, and there ply the trade of a female huckster. He frequented the notorious brothels, drove out the prostitutes, and played the prostitute himself. Finally, he set aside a room in the palace and there committed his indecencies, always standing nude at the door of the room, as the harlots do, while in a soft and melting voice he solicited the passers-by.’ He wore makeup and plucked out his beard hairs. Dressed as a woman, he married a strapping slave called Hierocles, and afterwards he kept contriving ways for Hierocles to find him in bed with other men and beat him. ‘He carried his lewdness to such a point,’ Dio writes, ‘that he asked the physicians to contrive a woman's vagina in his body by means of an incision.’

The most influential source for Avitus is the Historia Augusta, a very comprehensive collection of imperial biographies written by six different authors around the year 300. The Historia Augusta is a very interesting book. Unlike most Roman histories, it’s dense with primary sources: extracts from letters, speeches, pronouncements. It’s also packed with quotes and references from other histories, some of which are unattested in any other source. The only problem is that it seems to have been written as a piece of vicious revenge against all future historians. A few of its emperors are described issuing decrees or holding councils on dates when we know they were otherwise occupied being dead. Other people described in the Historia Augusta never existed at all. Neither did the other books describing them, or the historians who supposedly wrote those books. It points to whole libraries of unreal texts. Like a book that fell into our world from a parallel universe. Also, the six authors all write in exactly the same style, and their Latin is the Latin of at least a century after they were supposed to have been writing. (Imagine a Victorian novel in which characters all greet each other with ‘wassup.’) It’s all a big prank. But annoyingly, some of the material in the Historia Augusta is accurate. It’s just that when there are no other corroborations, we can’t know which parts. Whoever actually wrote it is a personal hero of mine.

Anyway, the Historia Augusta spends two chapters recording the sins of Avitus in no particular order. Besides his sexual debauches, it claims he was the first Roman to make pâté out of lobsters, the first to wear clothing made entirely from silk, and the first to drink from silver urns. He gave various important public positions to ordinary men—a barber, a mule-driver, a cook—‘whose sole recommendation was the enormous size of their privates.’ He fed his dogs on goose liver. ‘He sank some heavily laden ships in the harbour and then said that this was a sign of greatness of soul.’ He also kidnapped noble children from across Italy and tortured them to death. He tied his courtiers to a wheel half-suspended in the water so he could amuse himself by very nearly drowning them each in turn. Once, he held a banquet in which his guests were blanketed in so many flowers that some of them suffocated to death.

It’s hard to know if anything we’re told about Avitus is true. Lately, some institutions have announced that they’ll start referring to Avitus with female pronouns: the only empress regnant to have ruled from Rome. And maybe they really are honouring the gender identity of a distant trans ancestor—or maybe they’ve been taken in by the propaganda of the third century. The Romans were so scandalised by him that any wild accusation would have stuck—but we happen to live in a culture in which crossdressing is no longer considered worse than murder. (Maybe in a more relaxed future, David Cameron will be celebrated as a sexual pioneer for what he allegedly did with that pig.) Chances are that what really turned the Romans against Varius Avitus Bassianus wasn’t his luxuries or his sexual habits, but his faith.

Like many aristocratic children, Avitus grew up wandering. We’re not sure if he was born in Rome or in a distant province. His father had managed the capital’s aqueducts; later he was sent to Britain as procurator, and the young Avitus spent a good chunk of his childhood in York. But when he came to Rome as Emperor, it was with a new religion from the other side of the empire. A shabby, disreputable soldier’s religion out of the Middle East. Avitus was circumcised and refused to eat pork, and he worshipped a single god. What’s more, he believed that several generations ago, this god had taken physical form and come down to Earth. He had no respect for the traditional Roman pantheon. The vestal virgins were sacred to the goddess of the hearth, and the punishment for sleeping with one was to be buried alive, but Avitus took Aquilia Severa, high priestess of Vesta, as his wife. He rededicated the temple of Jupiter on the Palatine Hill to his god. Then he looted the sacred objects from the other temples and brought them there, so none of the other deities could be worshipped. On holy days he held banquets for the plebs, trying to convert them to the new religion. And in the end, they were converted; eventually, his religion would take over the entire empire. Just not yet. Avitus was too early. The Roman aristocracy hated his new god, and they hated him. So they hacked him to death and put the damnatio memoriae on his name. And afterwards, they packed his god onto a boat and sent it home.

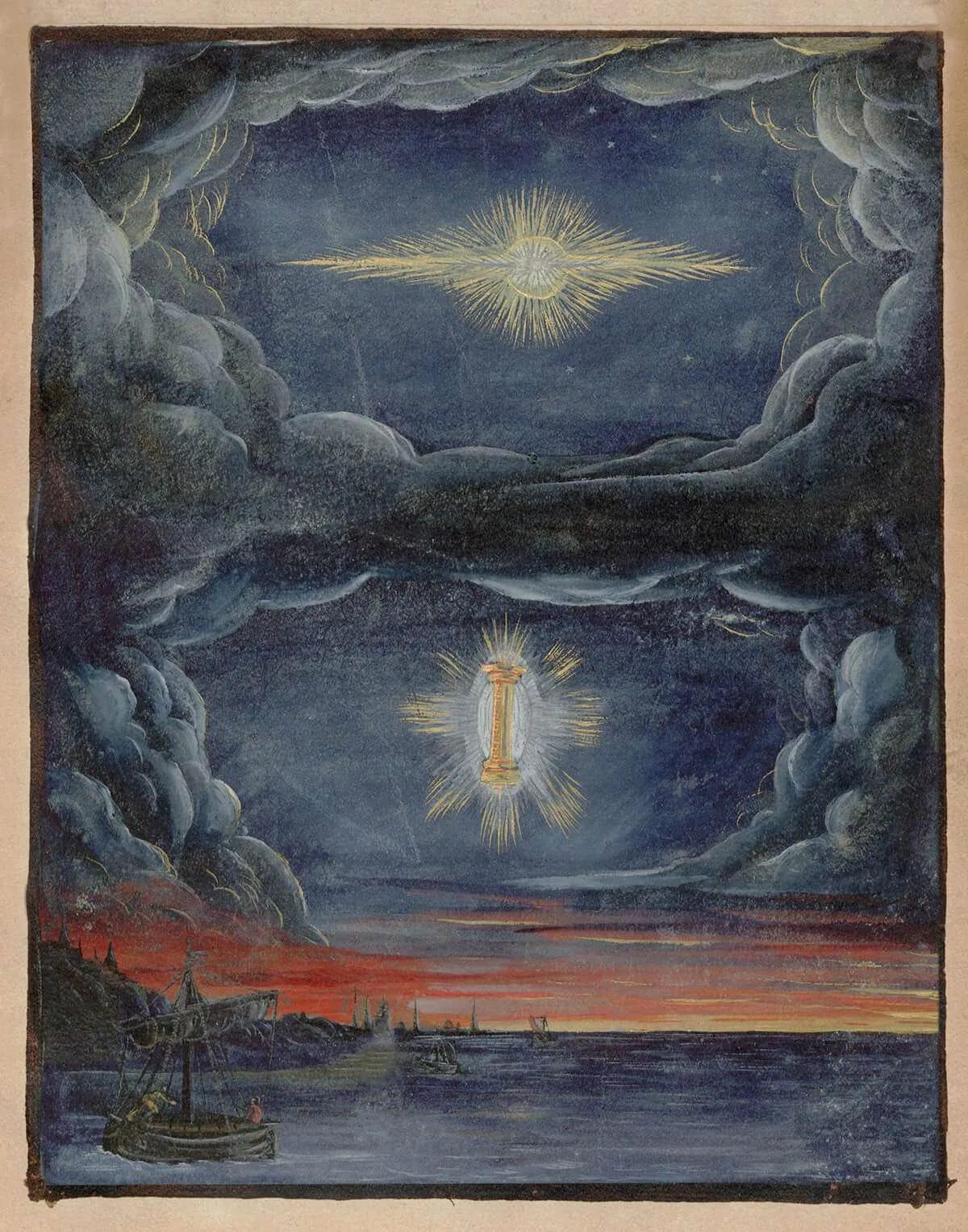

Avitus was not a Christian. He was the hereditary priest of a sun-god called Ilah al-Jabal, or the God of the Mountain, worshipped in his native city of Emesa, which is now Homs in Syria. Today, Avitus is better known by a Hellenised version of the god’s name, Elagabalus. But this sun-god really had taken physical form and come down to Earth. It was a meteorite.

Once, there were stone cults up and down the eastern Mediterranean: worshipping rocks from outer space seems to have been one of the distinctive features of Semitic religion. In Byblos, they worshipped a meteorite in connection with the goddess Aphrodite. Petra had one holy rock with a round shape and another like a rough cube. In Sidon, the black stone of Astarte was sometimes carted around in a two-wheeled chariot for processions. There was a glassy stone in a shrine on Jabal al-Aqra, which appears in the Book of Isaiah as Mount Zaphon, sacred to Baal. These cults are the prehistory of outer space. Our first encounter with the world beyond our world: not as a series of lights moving across the sky, but a zone of concrete things.

Like most prehistories, this one is very hazy. We know that people identified these stones as gods and worshipped them. We don’t really have any idea why, or what that even meant. Was the stone holy to the god? Or was it the actual god in physical form? Could you communicate with the god through the stone? Did people try? Did a meteorite stand for a link between Heaven and Earth, or something else? The sources we have aren’t telling us; most of our information about these asteroid cults doesn’t come from written documents, but from numismatics. Even in the Roman era, cities continued to strike their own coins, and local currency would often feature an image of the local god opposite the emperor (or, occasionally, the previous emperor defaced with the letter A). So we have lots of mysterious pictures of big inert rocks in the middle of colonnaded temples. The usual name for these stones is the Latin baetyl or baetylus. Pliny uses the word to describe a sacred stone that ‘absorbs the brilliancy of the stars’ and is ‘never found in any place but one that has been struck by lightning.’ His source here is Sotacus, who he calls elsewhere ‘one of the most ancient writers,’ but all his actual works are lost. The name baetyl might be borrowed from the Aramaic beth-el or house of the god, or might not. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, archaeologists started excitedly describing any and all holy stones as baetyls. So the omphalos at Delphi is a baetyl, and so is the mythic stone swallowed by Kronus in place of Zeus, and so are pretty much any round objects depicted in anything from the Minoan civilisation of Crete. Some of these theories are, admittedly, very fun. The Greek archaeologist Nanno Marinatos argues, based on Minoan seals of human figures reclining on what look like rocks, that if you fell asleep with your head on one of the holy stones, you’d have a mystical vision of the god or spirit it contained. She’s also argued that the word baetyl is hopelessly vague and unscientific and should be dropped by serious scholars. She’s probably right.

I can make some slightly loopy guesses of my own. What would a rock falling from the sky signify in the ancient Mediterranean? Maybe it would depend on who you were. In the classical universe, everything tends towards its rightful place: earth, as the heaviest element, sinks to the ground; fire, the lightest, flows outward to the edges of the cosmos. In his Meteorologica, Aristotle argued that shooting stars were pockets of moist vapour produced by the Sun’s effect on the atmosphere. Diogenes might have thought the stars were made of pumice-stone, but Aristotle knew better: it made no sense for there to be rocks in the sky. About a century before his birth, a bright object had been seen in the sky at Aegospotami on the Hellespont, a large burning rock that then crashed violently to Earth. Aristotle had a much more subtle explanation. There had been a comet, and there had been a falling rock, but these phenomena, while connected, were not the same thing. Comets, being fiery, dry out the air and cause great winds. The stone had been carried up in the night by one of those winds and then deposited back down at Aegospotami. Which makes perfect sense, given the information he was working with. An asteroid would be an inversion of the entire natural order.

But Semitic peoples thought differently. It’s notable that among Indo-European people like the Greeks, the chief god is usually some kind of sky deity: Zeus or Aswas or Tyr or Dyeus Pita. But in Semitic religions, you get the gods of, specifically, the storm. Enlil, Hadad, Baal, Yahweh. The difference is slight, but it’s there. The all-encompassing sky sets everything under heaven in its proper place, but the storm brings chaos. Trees uprooted; mountains laid low. Indo-Europeans worshipped the natural order in the form of the gods, but Semitic gods were always one step removed from the material universe. In the Theogony and the Rigveda, that universe exists before the gods, who emerge like worms from a cheese; in the Enuma Elish the gods war with each other before the creation of the universe, and the victors end up fashioning the physical world out of the corpses of the defeated. ‘He split her into two like a dried fish: one half of her he set up and stretched out as the heavens. He placed the heights in her belly. Her crotch—it wedged up the heavens—he stretched out and made it firm as the Earth.’ These gods transcend nature, which is why Semitic religion could tend towards aniconism, representing them as an abstract shape or not at all. A rock falling from the sky, a total inversion of everything that made sense about the world, might have been a decent metaphor for God.

But obviously this is conjecture. If that was how the asteroid cults imagined things, they didn’t tell us. They just put silent, mysterious rocks on their currency. This is why the brief reign of Elagabalus is so useful: for once, we get a (fragmentary, biased) description of how these cults actually worked. When Elagabalus brought his Syrian meteor religion to the heart of Rome, he turned the outraged Roman aristocracy into ethnographers. They didn’t care about it when it was only in the provinces and among the soldiery, but now they had to document this new and foreign religion. (Of course, Rome was theologically omnivorous, and it didn’t stay foreign for long. As I said above, Ilah al-Jabar did eventually end up taking over the empire. But this time, the sun-god came minus the big rock and some other specifically Semitic accoutrements, rebranded by the emperor Aurelian as Sol Invictus.) So Herodian, who also lived through the reign of Elagabalus, carefully describes the meteor in its temple. ‘No statue made by man in the likeness of the god stands in this temple, as in Greek and Roman temples. The temple does, however, contain a huge black stone with a pointed end and round base in the shape of a cone. The Phoenicians solemnly maintain that this stone came down from Zeus.’

He also describes the way Illah al-Jabar was worshipped, which was through dance: as priest, Elagabalus’ duties consisted of ‘dancing about the altars in barbarian fashion to the music of flutes, pipes, and every kind of instrument.’ When he brought the rock to Rome, the emperor staged a grand procession. ‘He placed the sun god in a chariot adorned with gold and jewels and brought him out from the city to the suburbs. A six-horse chariot bore the god, the horses huge and flawlessly white, with expensive gold fittings and rich ornaments. No one held the reins, and no one rode in the chariot; the vehicle was escorted as if the god himself were the charioteer. Elagabalus ran backward in front of the chariot, facing the god and holding the horses’ reins. He made the whole journey in this reverse fashion, looking up into the face of his god.’ He also continued to perform for it at regular intervals, dancing ‘to music played on every kind of instrument; women from his own country accompanied him in these dances, carrying cymbals and drums as they circled the altars.’ Herodian gives us the prim horror of the aristocrats forced to participate in these rituals. ‘The entire Senate and all the equites stood watching, like spectators at the theatre.’ These displays seem to have genuinely freaked the Romans out. They were very comfortable with animal sacrifice, temples as slaughterhouses, holy sites caked with the blood of ten thousand victims. But they did not like the combination of religion and dance.

This isn’t much to go on, but it’s something. There are a few other clues scattered around. As it happens, one minor Semitic stone cult actually managed to survive, in a certain form, from the ancient world continuously to the present day. Its followers still reach out to kiss or touch the stone that came down from Zeus. There are just under two billion of them.

The Hajr al-Aswad or Black Stone is set in the eastern corner of the Kaaba in Mecca. Ibn Abbas relates that the Prophet said that it came down from Paradise. Ibn Abbas also relates that when the stone came out of Heaven it was ‘whiter than milk, but the sins of the sons of Adam made it black.’ Ibn Umar relates that this is because when you touch the stone in genuine repentance, your sins are expiated; the stone swallows them. In the Fath al-Bari, ibn Hajar describes an unbeliever asking why, if sins turned the stone black, the touch of a Muslim doesn’t turn it white again. Commenting on this question, al-Tabari replies that it’s so the rock can serve as a lesson. ‘If sins can have this effect on an inanimate rock, then the effect they have on the heart is greater.’ Ibn Abbas relates that Mohammed also promised that on the Day of Resurrection, the Black Stone ‘will have two eyes with which it will see and a tongue with which it will speak, and it will testify in favour of those who touched it in sincerity.’

(Meanwhile, Wikipedia relates that when Adam and Eve were exiled from the Garden, the stone came burning out of the sky to show them where to build the first temple. This is a beautiful story and also very useful for my general argument, so I wish it were genuine, but as far as I can tell it’s completely made up. The citation points to a book by the British convert Martin Lings, in which the story about Adam and Eve does not appear. It’s also not in any book of sunnah. The Islamic orthodoxy is that the stone was carried down by angels to Abraham when he built the Kaaba. As far as I can tell, the Adam story was invented in April 2015 by a Wikipedia editor called The Herald, who identifies themselves as a Christian from Kochi in Kerala. The Herald appears to have spent over a decade writing perfectly respectable articles on Colombian landslides and the poetry of Robert Frost, for the sole purpose of burying this one fabrication. That fabrication now appears in articles on the BBC and, funnily enough, Arab News. It was also repeated by Shaykh Afifi al-Akiti, Fellow in Islamic Studies at Oxford, in an interview with CNN. Even great theologians just crib everything from Wikipedia. I’ve contacted The Herald for comment. We live in a fascinating world.)

Later Muslims didn’t know entirely what to make of the Black Stone. When he returned to Mecca, Mohammed had destroyed all the cult objects of the Quraysh. God is perfect and alone and stands entirely outside the universe; his worship should not be connected with any images or objects, any whispering sacred places of the pagan past. Al-Azraqi records that just one of the idols in the Kaaba was spared: the Prophet covered an icon of Mary and the infant Jesus, and told the Muslims to erase everything except what was under his hands. But he also left the Black Stone. During the Jahiliyyah, that stone had been sacred to the false gods of the Arabs; possibly the rain-god Hubal—but for some reason, instead of destroying it, the Prophet kissed it. Ibn Ishaq writes that he was the one who’d placed it in its corner, five years before his first revelation. The clans of Mecca had trusted him to handle their sacred object. Maybe he felt some nostalgia for that moment, before he’d gone to war with his own tribe. Or maybe he sensed, just for an instant, the interstellar chill radiating from that stone, this fragment of the dark and starry pit outside our world. Umar, the second Rashidun Caliph, is supposed to have said gingerly, on coming near the thing: ‘No doubt, I know that you are a stone and can neither benefit anyone nor harm anyone. Had I not seen God’s Messenger kissing you I would not have kissed you.’ Very reasonable. But if this is just a stone, if it can’t benefit nor harm anyone, if it has no numinous qualities, then why are you talking to it?

The Black Stone might have crashed to Earth from outer space, but it still remained in one piece. The sins of the pagans might have turned it black, but it would suffer far worse from the piety of Muslims. During the Second Fitna, the Kaaba was burned down in the Umayyad bombardment of the city, and the stone cracked into three pieces. Afterwards, they were held together in a silver frame and returned to the foot of the sanctuary. A hundred and fifty years later, Mecca was sacked in the middle of the Hajj by the Qaramita. They massacred pilgrims as they were circling the Kaaba and left their bodies scattered around the mosque. They prised the stone out of its corner and took it with them to Bahrain. The Abbasids offered fifty thousand dinars for its return; the Qaramita replied that ‘we took it by order, and when an order comes to restore it, we shall do so.’ That order must have come, because two decades later the stone was returned by being wrapped in a sack and thrown into a mosque. This time it broke into seven pieces. It must have suffered more unrecorded accidents, because by the nineteenth century it had been shattered into a dozen or more fragments. Currently there are only eight, set in cement. The Sokollu Mehmet Pasa Mosque in Istanbul claims to have four more pieces; there’s also one alleged shard in the mihrab of the Blue Mosque and one set in the wall of the tomb of Suleiman. The parts of the stone that remain in Mecca are under the protection of the Saudi monarchy, who refuse to allow any scientific analysis of its composition. It may or may not have been a meteorite: the rubble of an alien planet; a visitor from the void.

Even if the Black Stone really was a baetyl, though, its significance in Islam is limited. All orthodox Muslims follow Umar: in the end, it’s just a stone. A marker for your tawaf. During the two decades when it was held by the Qaramita, pilgrims just reached out to kiss the point where the stone used to be. But there are also traces of what looks a lot like the rock-cult in the other surviving Semitic religion: the one that happens to be my own.

In the book of Genesis, Jacob is fleeing his father’s house and the deadly revenge of his brother, heading north for the uncertain hospitality of Laban the Aramean. He has nothing in the world but his stolen birthright. When night comes, he’s still in the wilderness. There’s nowhere to sleep except on the cold ground, so that’s what he does, shivering among the dry grasses with a rock for a pillow. And then he has a vision, of a bright ladder reaching up to Heaven, with throngs of angels constantly streaming up and down. He hears the voice of God, promising that one day his descendants will teem like particles of dust over the land. But when he wakes up, his conclusion isn’t that he, Jacob, is a very special person to have spoken with God. Instead, he concludes that this is a very special rock. ‘And Jacob awakened from his sleep, and he said, ‘Indeed, the Lord is in this place, and I did not know it.’ And he was frightened, and he said, ‘How awesome is this place! This is none other than the house of God, and this is the gate of Heaven.’ And Jacob arose early in the morning, and he took the stone that he had placed at his head, and he set it up as a monument, and he poured oil on top of it. And he named the place Beth El.’

This is all eerily familiar. But actually, two of the most distinctive features of this story—the dream, and the name—don’t have any proven link to the meteorite-cults of western Asia. The idea that you can make contact with a deity by sleeping on its sacred stone is a conjectured feature of Cretan, not Semitic religion. The word baetyl was only consistently applied to these stones long after the composition of the Bible. The omphalos at Delphi was anointed with oil, but there’s no record of anyone doing the same to any of the sacred meteors of the Middle East. Still, there’s something here. The hint of an astral substrate within what would become Judaism, in which God isn’t everywhere but lurks in a few special places, hiding in the hillsides with the nature-demons. In which the I Am isn’t a burning fire, but a lump of rock.

Here’s another mysterious story from the Bible. King Saul and three of his sons are killed by the Philistines at the Battle of Gilboa; this is followed by a civil war between Saul’s remaining son, Ish-bosheth, and a charismatic pastoralist warlord called David. They fight a series of bloody battles; slowly the warlord picks off the loyalist forces, captures hill-forts, raids towns and villages. The House of Saul do some raiding of their own. It must have been a miserable time to be alive: two armies jointly making war against the general population. Eventually, though, David starts to gain the upper hand, and two of Ish-bosheth’s captains decide to put an end to it: they walk into their king’s house, cut off his head, and bring it as a gift to David. People can have a strange sense of honour: David has the two captains killed, their hands and feet cut off, and their bodies hung up for everyone to see. Then he tenderly buries the head of Ish-bosheth with all the proper rites. Finally, he declares himself king. After a series of military victories against the Jebusites and the Philistines, he retrieves the Ark of the Covenant and brings it to his new capital in Jerusalem. To celebrate, he sacrifices a bull and a calf. Then he performs his worship, in exactly the same way Elagabalus worshipped in Rome. 2 Samuel 6:14: ‘And David danced before the Lord with all his might.’

What is the Ark of the Covenant? There are a lot of entertainingly insane theories on where it ended up, but where did it come from? According to the biblical account, God instructed Moses to build it after the exodus from Egypt, including some very precise schematics: it’s a box, 2.5x1.5x1.5 cubits, made of acacia wood plated in gold, for God to live in. The ark contains the tablets of stone bearing the Law, but it also holds God’s physical presence on Earth; what would eventually be called the shekhina. The holy presence makes it an incredibly dangerous object. Even Moses—who climbs mountains to speak with God, and descends with a glowing face—can’t come near, ‘because the cloud abode thereon, and the glory of the Lord filled the tabernacle.’ When two of the sons of Aaron make an unprogrammed offering of incense before the Ark, they’re immediately consumed by the fire of God. Later, when it’s stolen by the Philistines, every city they bring it to is afflicted with plagues. During David’s transportation of the Ark to Jerusalem, a man named Uzzah steadies it with one hand and is immediately struck dead. (Rudolf Otto comments that the wrath of God ‘has no concern whatever with moral qualities. There is something very baffling in the way in which it is kindled and manifested. Like a hidden force of nature, like stored-up electricity, discharging itself upon anyone who comes too near.’ Later, he suggests that God’s wrath and God’s love are really the same thing, a terrible and overflowing majesty. Love is also a kind of fire.) The Ark is, in a sense, a weapon. Joshua carries it around the walls of Jericho; David takes it with him on his military campaigns. Finally, Solomon builds a temple arranged around a secret room, the Holy of Holies, in which the Ark could be kept in safety. Only the High Priest is permitted to visit the Holy of Holies, once a year on Yom Kippur, to stand in the presence of God.

In some mystical traditions, the Ark and its tabernacle are a metaphor for the universe. The language with which Moses observes its creation in exodus directly echoes the language with which God observes the creation in Genesis. The dimensions of the Ark represent the dimensions of reality. Its gold rings and wooden faces are the architecture of the galaxies and the secret structure of the human heart.

I hate to be pedantic in the face of all this grand metaphor. But the fact remains that the story as told isn’t true. Moses never actually existed, and David and Solomon probably didn’t either. The actual origins of the Jewish religion are documented in the later books of the Bible, the ones where one prophet after another castigates the children of Israel for worshipping idols instead of the one true God. The Hebrews hadn’t turned their backs on God, though; he was something new. The kings of Israel and Judah were Canaanites, tribal chiefs of the Iron Age, worshipping a warrior-god called Yahweh alongside a small stable of other local deities. El the creator, Baal of the air, Anat the huntress, Asherah queen of snakes. But over centuries they were prodded grudgingly into monotheism by a succession of mad-eyed wilderness poets. (Maybe they saw something in the sky.) The Moses narrative might have been a relatively late invention: in the Book of Chronicles, it doesn’t appear at all; instead we start with a genealogy from Adam to David and the other chiefs of the Hebrew hill-clans. In between, the children of Israel war and raid cattle, and none of them go anywhere near Egypt. There was no wandering in the desert. Nobody carried God in a box to the Promised Land.

Still, the pedantic descriptions of the Ark of the Covenant do indicate that it might have been an actual ritual object. But if it was already there in the time of the prophets, it couldn’t have belonged to their religion, because their religion barely existed yet. It must have been holy to the old Canaanite faith, and only later integrated into what would end up becoming Judaism. The biblical account claims that the Ark contained two tablets of stone, and for all we know that might be true. But if it is, those tablets would not have been inscribed with the Ten Commandments. If you were brave enough to open it up, you might find two black, almost glasslike stones. Two idols; two gods: Yahweh and his consort Asherah. Two pieces of a meteorite.

In 2013, an asteroid fell into the Earth’s atmosphere over the city of Chelyabinsk in Russia. It flashed over the factories, the low apartment buildings, the marshes, the suburban tracts of wooden houses on unpaved streets. When the asteroid burst in midair, it was briefly brighter than the Sun. Windows were smashed across a hundred kilometres. A power not of this world. Afterwards, a local named Andrei Breivichko founded a group he called the Church of the Chelyabinsk Meteorite. The meteor, he said, was holy. Anyone trying to remove it from its sacred impact site would be punished. It contained psychic instructions for a new and moral society; it belonged in a temple. If the Russian authorities tried to put it in a museum—which is what they did—he prophesied that the country would fall into a series of costly and terrible wars.

There’s a chance that the entity billions of us now refer to as God began, three thousand years ago, as a small lump of rock. Before he was the sole creator of the universe, lord of everything, beyond space, beyond time, not a being among beings but the ground of all being—before he knew the content of your soul, before he walked with you in the darkness, before he could love you when you hadn’t even been born—before that, he spent billions of years erratically orbiting the Sun. For five seconds on the cusp of history, he burned brightly in the sky. Maybe God is buried somewhere in the soil of the Middle East. Or maybe he cracked, or was ground to nothing. Maybe a portion of the desert is the dust of God.

One of the worst sins you can commit in the humanities these days is cultural evolutionism. It’s not helpful to think of the past as half-formed or inchoate. The religions of the ancient world weren’t primitive versions of what we have now; they were complete, fully articulated belief systems that simply existed then rather than now. Not progress; just change. But there’s something about the asteroid-gods that brings out the Hegelian in me. It’s very hard for me not to feel that the notion of an abstract, infinite, and loving God represents a significant conceptual development on the awestruck worship of a strange stone that fell out of the sky.

Except—one of the things I keep coming against, the more I read about the meteor cults, is how much about them we simply don’t know. The people who think they know about them know even less. Skimming a few Wikipedia articles will actively make you more ignorant. All we really have are strange clues, vast gaps, and mad inventions. The branching lies of the Historia Augusta; the man in southern India who decided one day to invent a piece of Islamic folklore. Or the dark space inside the Ark, where anything from any world might lurk. I like the mad inventions. There’s a real joy in drawing your fragile web of inferences over the gap of everything we don’t know, certain only that all your conclusions will be wrong. And a meteorite is a lump of not knowing. This thing that doesn’t quite make sense; this object that’s arrived from outside of everything we can understand. It does not belong under our skies. There are worse things to worship. This world is very, very large, and maybe entirely senseless; we will never comprehend it all. But here’s a piece of its otherness. Here, right here, black and in your hands.