A dreadful dim fire

Everything you hate is actually good

Reviewed: Oppenheimer (Christopher Nolan, 2023) Napoleon (Ridley Scott, 2023) Wish (Chris Buck and Fawn Veerasunthorn, 2023) Lost Highway (David Lynch, 1997) Stalker (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1979) The unnameable object of desire (???, 200,000 BC)

Not long ago, I woke up suddenly in the middle of the night with a startling and beautiful insight shimmering on the surface of my mind. It was brilliant and it was true and I could already feel it fading, going dull on contact with the waking world like cut magnesium. I had to write it down. I knew that we all wake up multiple times every night and don’t remember any of it in the morning. I was a sort of brief parallel version of myself, outside the normal stream of being, and possessing special knowledge. Very soon, I would vanish into a forgetfulness not unlike death. But before that happened, I had to tell my other self what I knew. I sat up in bed and frantically scribbled an outline of my beautiful insight, trying to capture as many of its finer details as I could before they melted away. Then, once it was done, I turned over and collapsed into a deep, deep, dreamless sleep.

I’m not sure I managed to capture everything. But the main idea survived. On waking, I found a note. It consisted of a single word:

NAPOPPENHEIMELEONER

I think I remember some of the concept. A script for the greatest blockbuster in history, in which we see Napoppenheimeleoner, terrible amalgam of two great warriors, winning battle after battle and then wandering the fields of mangled corpses in nebbishy regret, doing his Maintenant-je-suis-devenu-la-Mort routine as ranks of Russian cavalry in gleaming uniforms vanish into the growing ball of nuclear fire. At the time, I’ll admit, I had not actually seen either film. But I did watch Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer shortly afterwards, with the idea that maybe if there was anything interesting there I could obey the mysterious demands of my shadow-self and write something fun about the monstrous Napoppenheimeleoner. But there was nothing interesting there. Oppenheimer is bafflingly, pointlessly soulless and shit. Less an actual film than a three-hour-long trailer: just snapshots, stitched together, each scene lasting a few minutes at most, until you start to get something like motion sickness. Here’s J Robert in a classroom. Now he’s riding horses in the desert. Now he’s having sex with a woman; now she’s dead. There’s no space for anything to breathe. On to the next scene. At no point in this mad rush is there any attempt to portray any of the actual sensuous texture of life, which is one thing cinema can be quite good at. What are Oppenheimer’s living quarters at Los Alamos like? What does he do when he wakes up in the morning? What did building the atom bomb actually involve, and what did it feel like to be knowingly working so hard to kill so many people? We literally never find out. We just cut from one tedious administrative meeting to another. You get the sense that Nolan isn’t really interested in much. Not nuclear physics, not the terrible responsibilities of the atomic age, or the romance of Communism, or the cruel machinery of the US government; in fact, he doesn’t even seem to care at all about J Robert Oppenheimer, as a man or a totem. What he cares about are the following: firstly, shoving as many scientists and politicians in front of our faces as possible, so we all appreciate how thoroughly he’s done his homework, and secondly, employing a Mirror-wannabe non-linear storytelling technique for no apparent reason whatsoever. It sucks.

But I wasn’t really surprised that Oppenheimer is not very good. This is Christopher Nolan, the man who once set an entire film inside a dream but couldn’t think of anything better for his characters to do in there than shoot guns at each other. I wasn’t even surprised that film critics—people whose only job it is to tell the difference between a good film and a bad one—unanimously loved this thing. I have occasionally done some very ordinary magazine film reviews myself, so I’m not excepting myself when I say that film critics are all a bunch of plankton-eating mental bivalves whose entire critical intelligence consists in wrenching open their calcified flaps to filter any specks of mediocrity floating around in the abysses of our culture, and the only thing they’re really good for is being boiled alive in a big pot with some shallots and parsley. Of course they thought Oppenheimer was a towering achievement; of course it’s about to win a bathtub full of awards. These people are towered over by seaweed. What did surprise me, though, was the response to Ridley Scott’s Napoleon. Suddenly, these same creatures could quite easily identify a film that tried to do too much and ended up hardly doing anything at all, even with an absurdly bloated runtime. So now you can spot limp unspectacular acting, can you? Now you know when a big statement movie doesn’t actually have any propositional content? Now you can tell when a once-vaunted British director is clearly over the hill?

What the critics didn’t spot, though, is that Napoleon isn’t really about the historical Napoleon Bonaparte at all: it’s about the secret mechanism of the human soul. Earlier this year, I wrote a big rambling screed against therapeutic realism, practically begging for some mainstream pop culture that does something, anything else: art that doesn’t always treat its human material as tediously explicable, that doesn’t feel the need to render everything in the dull flat language of pop-psychological literalism, but is willing to recognise the dark void of the senseless that distinguishes a free human being from an automaton in flesh, and which must be represented in symbols rather than signs. And finally, mainstream culture is doing precisely that. This is important! Every year, mainstream culture loses a little more ground, and some people might celebrate: after all, mainstream culture is failing because it has, for the last decade-plus, mostly been a culture of lazy, joyless sequels and bizarre moral didacticism. But look at what’s replacing it. Two-second clips of people falling over. ChatGPT fed into text-to-speech. The closest thing to an extended, coherent narrative is about singing heads that emerge out of toilets. People will sit for hours and watch a live stream of a woman describing emojis and sometimes pretending to eat them. Mmm ice cream so good! Whatever this is, a functioning shared mainstream culture in which people are actually trying to make something worthwhile seems vastly preferable. So it’s very good news that Hollywood is once again trying to speak to the human condition. But because you are addicted to your own chains, you hate it. You hated Napoleon. You hated Wish.

Look: I understand why people would not want to like Wish. This media product is a big smug self-referential tribute act with which the Walt Disney Company is commemorating its hundredth anniversary, and who has any warm feelings for Disney? Who wants to nonconsensually attend someone else’s birthday party? It doesn’t help that the film garbles bits of plot and style from Pinocchio and Snow White and Sleeping Beauty in what was clearly supposed to be a nostalgic tribute, but feels more like a rummage around in a mass grave. It doesn’t help that our main character is the same main character—brave and determined, with a strong sense of justice, and willing to risk everything to help her friends, but also for some reason physically clumsy to the point where you wonder if she ought to be wearing some kind of padded helmet—that seems to have been injected into every single mass-culture commodity on the planet, including those that are notionally for adults. It doesn’t help that the jokes aren’t funny. Or that every scene has the cheap glowing aura of an AI-generated image. Or that the songs have lyrics like this:

So I look up at the stars to guide me And throw caution to every warning sign If knowing what it could be is what drives me Then let me be the first to stand in line

People have tried to tell me that this verse does actually make sense. I’ll go into fits about how the songwriters behind these lines—whose names, incidentally, are Julia Michaels and Benjamin Rice—have each produced a slew of Top 40 hits and won various awards, which means that the people who generate our mass culture, the people who are paid a presumably eye-popping amount to write the songs that will be heard by millions upon millions of people, literally don’t know how words work. Not just uninspired—actually illiterate. This has to be some kind of civilisational low point. Surely we have nowhere left to sink after this. But apparently, I’m overreacting. Yes, ‘throw caution to every warning sign’ is a monstrous failed clone of an an ordinary English idiom; still, you know what they mean. And I have to grudgingly admit that yes, I do know what they mean. The next one is trickier. ‘If knowing what it could be is what guides me’—what is this it? Is it caution? Is it the warning sign? Is it the same dummy it you find in phrases like it’s raining? And what is the what that the it could be? These are just words, packed in here like styrofoam to fill the space… I’m told that this also makes a kind of sense. It is the future; this person is driven by their hope for a better future. (In which case, wouldn’t it make far more sense to have ‘how it could be’ instead?) But I absolutely refuse to budge on the last one. ‘Let me be the first to stand in line.’ What line? First to stand in line for what? To change things for the better, apparently. Is there a line for that? Is there a place to queue up? Some bureau of changing things for the better? What on earth are you talking about? And besides—if you’re the first to stand in line, then there is no line. There’s just you! Standing!

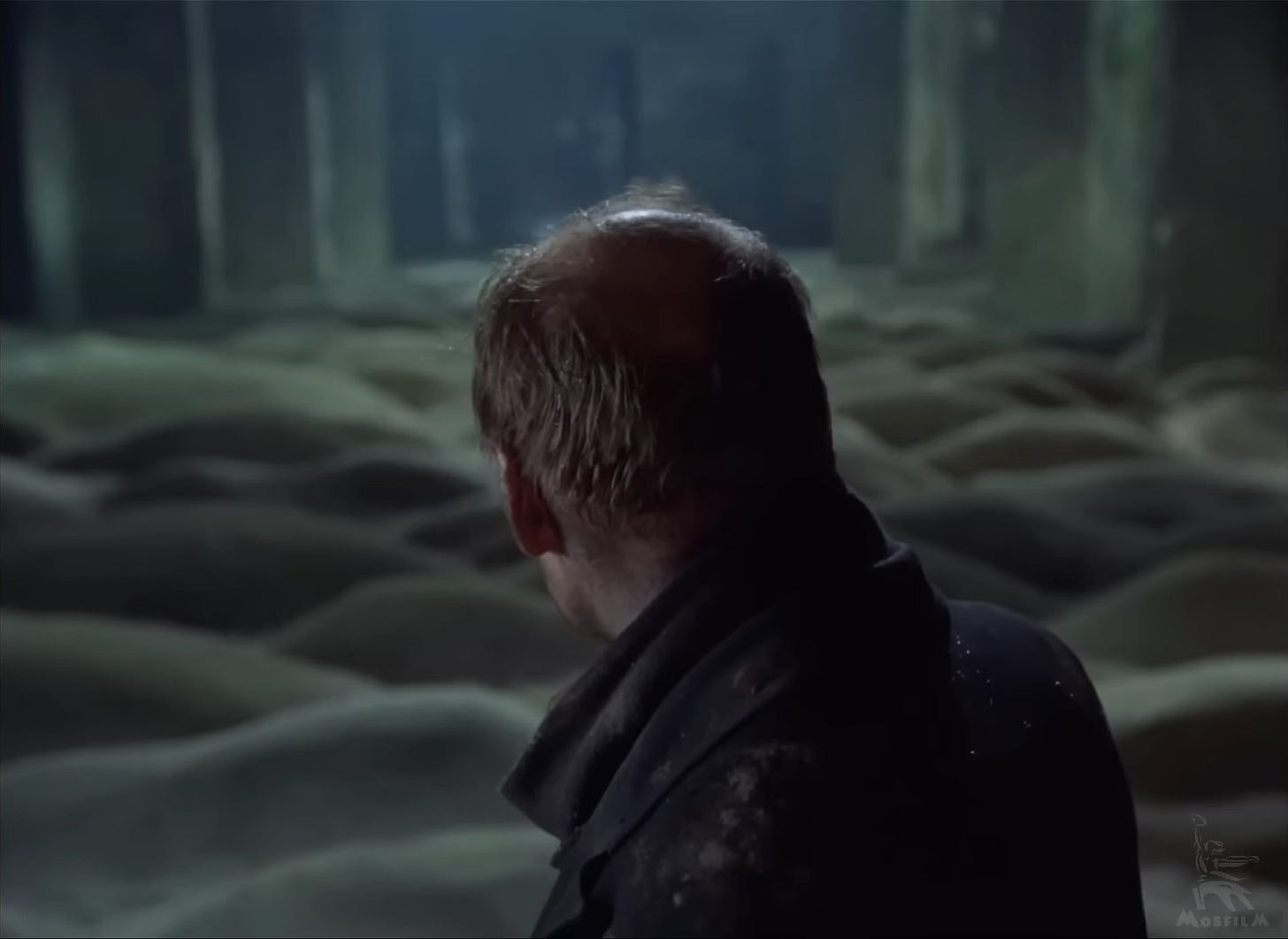

So like I said, I understand why you wouldn’t like Wish. All I’ll say is this: if you didn’t like Wish, but you did like Andrei Tarkovsky’s beloved late-Soviet depressive masterpiece Stalker, then you are wrong, because these two films are, in fact, exactly the same film.