The repulsive crust

Against A24 Brain

About half a decade ago, people kept telling me to watch BoJack Horseman. Oh, I think you’d really like it, Sam, they’d say, as if I had ever liked anything even once in my life. It’s about a cartoon horse, they’d say—but get this, the horse has mental health problems.

This did not fill me with anticipation. But because I am immaculately generous and open-minded and always willing to give even the worst of my enemies a chance, I sat down and watched BoJack Horseman. Each episode consisted of about twenty minutes of wacky animal-based comedy, and then five minutes of a giraffe recounting its sexual trauma or a sea otter weeping about the lost dreams of youth. Apparently, this made people feel seen: here was a TV show that spoke to the real and complicated feelings that surround our everyday lives, that gave those feelings shape. I made it up until the episode in which a woman who is married to a dog tells her dog-husband that she’d always dreamed of having a big book-lined library like in Beauty and the Beast, so her dog-husband has one built for her in their home, but the woman gets upset and says that it was a fantasy that belonged to her alone and the dog had no right to make it real, which is why they have to divorce. As it happens, this was exactly how my last two relationships ended. It was all too raw. It pierced me deep to the heart of my being. I had to stop watching.

A few years later, people kept telling me to watch Better Call Saul. Oh, I think it’s right up your alley, Sam, they’d say, as if my alley is found on any map. It’s about the fast-talking comic-relief character from a prestige drama, they’d say—but get this, the comic-relief character has mental health problems.

So I sat down and watched six seasons of Dark Lionel Hutz. I started imagining all the other characters whose important backstories needed to be fleshed out. We need to make them more human. We need to make them feel real. How about a lusciously filmed period drama called Basil? A fourteen year old kid, gangly and awkward, lost in a grey industrial English town. The other children mock him relentlessly for his height. He lives with his father, a brooding, brutal man who never mentions what he did in the war—but the pallor of it seeps into every corner of their house, the corpses in the tank tracks and Dresden in flames. Young Basil has the opportunity to break the cycle of trauma, but over sixty hours of TV we watch the good in him slowly die. He turns to mockery. He turns to violence. The girl he loves can’t bear to look at him any more; she no longer recognises the bruised but hopeful innocent she once knew. In a fit of despair, Basil marries a distant, domineering woman he’s barely met and doesn’t much like. This is all he deserves. In the final scene, with his soul in tatters, he buys a hotel in Torquay.

Lately, people have been telling me to watch Beef.

Beef is an A24/Netflix drama about a road-rage incident that explodes into a full-on vendetta between two Asian-Americans from very different backgrounds. Danny Cho is a loser who keeps trying to manipulate his little brother into working for his failing contracting company. Amy Lau is a successful but highly strung girlboss in octagonal glasses. Our two heroes start trying to sabotage each other in more and more extreme ways. This is not a bad idea for a TV show; in fact, it’s a very good one. A bitter, episodic half-hour comedy, like Tom and Jerry, or Wile E Coyote and the Road Runner, or Popeye and Bluto, but live-action and for adults. Or like the Icelandic sagas with their vastening spirals of revenge. A kind of giddy, lurid exploration of all the ways you can fuck with someone’s life. Doing it right would take a degree of creativity, but the result would be very fun. Real fun always has a breath of sadism.

This is not the Beef we got. Instead, our enemies mostly just leave each other nasty voicemails and obsess over their feelings. There’s one episode bloated with flashbacks. Danny secretly destroyed his brother’s college application letters—because he’s codependent and insecure, because he couldn’t face the thought of his younger brother leaving and doing things for himself, because he didn’t want to lose his little friend and occasional punching bag. Meanwhile, as a child, Amy witnessed her father’s infidelity with a white woman and didn’t say anything, because she knew that if she wasn’t always sweet and good then nobody would love her. It’s a miracle that the word trauma doesn’t appear until the final episode, in which our two enemies take hallucinogens together, finally unpack their fucked-up childhoods, recognise their shared vulnerability, and become friends.

It was the college-applications bit that really stuck with me. This kind of thing is an almost perfect instance of how we construct our complex, nuanced, morally difficult characters. And because culture doesn’t just reflect social reality but is also a site in the production of social reality, that scene is also part of our general-purpose map of other people and ourselves. A long time ago, people considered the self as a kind of field of contest for competing outside influences. The soul of Adam mingles both sparks of light and dark qlippot. It can be hard to hear the moral command of God through the demons whispering in your ear. We are beset by passions: that before which we are passive. Then, for a while after that, there was simply character, which could be good or bad, and which had something to do with heredity and possibly the precise pattern of bone ridges on your skull. Novels from this era tend to spend a lot of time on physical description, because the tilt of a nose or the bulging of an eye say something significant about the person we’re meeting. We don’t really do that any more. We have learned psychology: we know that a person is composed primarily of feelings and experiences. Our feelings determine our experiences, which is why it’s important to be very acutely aware of them. But our experiences can also shape our feelings, and the word for when this happens is trauma. One of the important functions of culture is to give you a better understanding of the feelings and experiences of others. But it can also show you what happens when your feelings and experiences are out of balance, and maybe, just maybe, how to get them in order again.

This system is fine. It provides a minimally coherent account of the human soul; none of these paradigms are really any better or any worse than the others. But it seems obvious that most of the characters created under the aegis of this system do not remotely resemble actual people. You start with the idea that humans are made of named and identifiable feelings, and then conclude that to invent a believable human, you have to stuff those feelings into everything. The result is the dog-man divorced over a magical book-lined room, or Danny destroying his brother’s college applications—and people do not act this way.

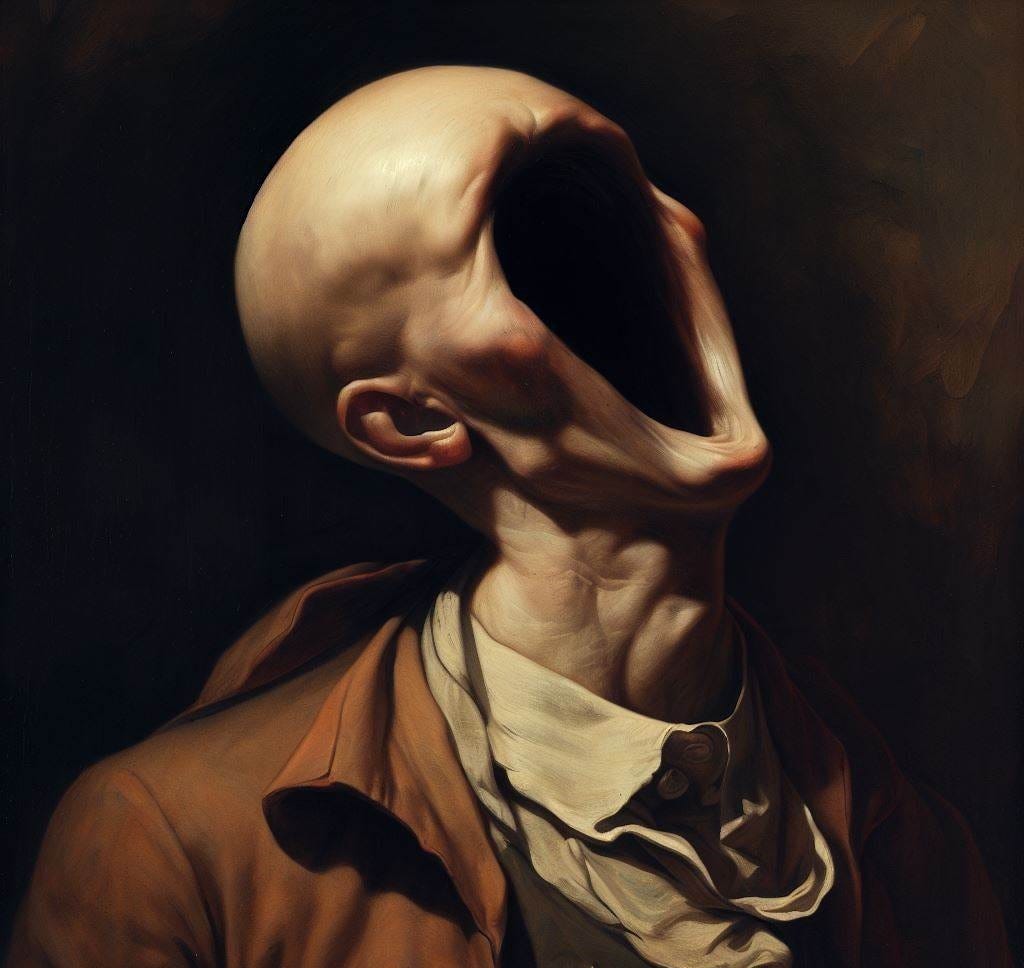

I don’t mean that people never do things that are cruel, selfish, weak, petty, and vicious. But I do not think they ever do it in a way that’s so tediously explicable. It’s all far too neat; it all makes far too much sense, this moment on which a person’s entire being is supposed to hang. When actual people act, there’s always an element of the inexplicable at play, the sourceless molten stuff we call human freedom. An abyss in the other, the dark hole of their subjectivity. But these people are wind-up toys. Try comparing them to the entertainments of the past: Flaubert or Eliot or Shakespeare. You can work out where Emma Bovary is headed right from her beginning, but her mind still dances. Hamlet might have been the first truly psychological hero, but he’s still an excruciating mystery to us and to himself. ‘O, what a rogue and peasant slave am I!’ He would like to feel things he doesn’t feel, and to act in ways he doesn’t act. Why doesn’t he? Not clear! There’s room to wonder, which is how you know he’s alive.

Even Freud never claimed to have completely understood the human mind; he always found himself stepping back, in something like terror, from its vastness. His theory of trauma is a grand one; as he writes in Beyond the Pleasure Principle, any working account has to encompass ‘the history of the earth we live in and of its relation to the Sun.’ For Freud, the last great mystic, our neuroses are made of the same stuff as myth. They speak to us from our animal prehistory and the inorganic world that was there before. But here, watching Beef, everything is completely comprehensible; it all fits together like a jigsaw. Spending too much time around prestige entertainment is like talking to one of those first-year psychology students who think their course of study will let them essentially read people’s minds. Or like encountering the mewling, hapless, flayed-open version of yourself that your girlfriend constructed out of Instagram slides.

In an early essay, Walter Benjamin complained about ‘the dreadful cobbling-together of disparate elements that loosely make for character in novels of an inferior sort. There, the national type, the regional type, the individual person and the social person are pasted one to the other in puerile fashion, and the repulsive crust of the psychologically palpable covering it all completes the mannequin.’1 He lived in a golden age and didn’t even know it; today, we’re left with just the repulsive crust of the psychologically palpable. Hollow, fleshless, inflatable men, with the repulsive crust and then only air underneath.

This is what I’ve started calling therapeutic realism, or A24 Brain: the brain according to A24. Not because it’s unique to A24 culture-commodities, or because it’s present in all of their output.2 But no one does crap psychology quite like your favourite indie film distributor.

Take, for instance, the celebrated horror films of Ari Aster, Hereditary and Midsommar. These two are essentially homages to the last generation of horror films: Hereditary is a reworking of Rosemary’s Baby, and Midsommar is a twenty-first century Wicker Man. Aster doesn’t do anything as crude as deconstruction. He plays all the classic horror tropes completely straight. The creepy haunted ouija board, the creepy friendly European pagans. What makes his films clever and new is, firstly, Pawel Pogorzelski’s excellent cinematography, and, secondly, a hefty dose of neurotic psychology. The characters in classic horror are slight by modern standards; their main personality trait is high-pitched screaming. But Aster’s are heavy with feelings and experiences. I remember being impressed by this at first. Except—isn’t horror already a language for talking about the self? It gets into the psyche by the back door, which is fear; it addresses the parts of ourselves that are shadowy and inexplicable, sometimes monstrous. Like the joke or the dream, it speaks in a language that’s much more real than that of psychological literalism. Symbols rather than signs. It expresses; it does not need to describe. So what’s the point of plastering over all this much more potent stuff with facile psychology? This isn’t more grown up than traditional horror; it’s the visual equivalent of riding a bike with stabilisers. It’s like trying to eat the menu. In the end, it’s just not very good.

But obviously, Aster spawned a whole minor genre of films that feel the need to literalise every metaphor. The worst offender here is possibly last year’s Men, from Alex Garland, who is capable of better: a film that is desperate to say something, filled with the heavy crossword-puzzle energy of saying something, but without really having any idea what it wants to say. Maybe the problem is that Alex Garland is, quite notably, a man. A female filmmaker might have been able to leverage some specific complaints about actual male behaviour; Garland has to sermonise against an abstraction, with just the vague material of 2010s-vintage kill-all-men feminism as his ammunition.

So his heroine—traumatised, obviously, and feelings-ridden; eminently real—takes a self-care break to a sleepy English village where all the men look the same and all proceed to gaslight and objectify and microaggress her like the cartoon misogynists from a Reddit thread. All these men are, it turns out, masks worn by the Green Man, which is an architectural motif usually found in mediaeval churches. Nobody really knows what the Green Man means, although he almost certainly wasn’t, as the usual types like to assume, a pagan deity in disguise. Here, though, he’s practically surrounded by flashing lights and blaring sirens that say ‘PAGAN GOD OVER HERE!’ and ‘GET YOUR NATURE SYMBOLS!’ and ‘HERE IT IS FOLKS: THE WILD WORDLESS UNTAMED EARTH!’ An inversion of the usual sexist schema, in which women are identified with nature and men with culture: here it’s the men who express the bubbling instinct of the land, and every time some man spreads his legs too wide on the subway, you are witnessing a force as thoughtless and eternal as the sea. Which would mean there’s no possibility of reconciliation, but my beef isn’t really with the reactionary gender politics of the thing. I don’t think Garland was intentionally endorsing political lesbianism. But this is what happens when the crap-psychological standpoint is confronted with the fullness of actual human life, a fullness that necessarily includes evil. Everything that can’t be boiled down to feelings and experiences must be isolated, rejected, spat back into the churning vortex of nature. This is not within me, it says. I’m a good person. I go to therapy.

Speaking of green men, though: I waited through a series of long, lonely lockdowns to watch The Green Knight, as it was delayed over and over again. It was practically the only thing that kept me going through the dark winter of 2021. On the other side of this, I knew, there would be a moderately decent film adaptation of possibly the finest piece of narrative ever written in the English language. And then I watched it, and I wished the virus had finished me off while I still had hope. I am not one of those people that gets all antsy if a film doesn’t cleave perfectly to the book; when an adaptation gets too reverential you start to wonder why they bothered making it in the first place. But novelty for its own sake is hardly better. Here is how Gawain and the Green Knight describes our first glimpse of the Green Chapel:3

He gazed all about: a grim place he thought it, And saw no sign of shelter on any side at all, Only high hillsides sheer upon either hand, And notched knuckled crags with gnarled boulders; The very skies by the peaks were scraped, it appeared. Then he halted and held in his horse for the time, And changed oft his front the Chapel to find. Such on no side he saw, as seemed to him strange, Save a mound as it might be near the marge of a green, A worn barrow on a brae by the brink of a water, Beside falls in a flood that was flowing down; The burn bubbled therein, as if boiling it were. He urged on his horse then, and came up to the mound, There lightly alit, and lashed to a tree His reins, with a rough branch rightly secured them. Then he went to the barrow and about it he walked, Debating in his mind what might the thing be. It had a hole at the end and at either side, And with grass in green patches was grown all over, And was all hollow within: nought but an old cavern, Or a cleft in an old crag; he could not it name aright. ‘Can this be the Chapel Green, O Lord?’ said the gentle knight. ‘Here the Devil might say, I ween, His matins about midnight!’

The Green Chapel is a long barrow, one of the Neolithic mounds that dot the island of Britain. We can hear the mediaeval imagination trembling before a much older world it does not know how to name. The barrows are some of the most ancient structures to survive, built some six thousand years ago; next to the barrow-builders, the men and women of the Middle Ages lived practically yesterday. This place is numinous. It belongs to a wilder, weirder god. But here is how the Green Chapel appears in the A24 version:

There’s some nice creepy overgrowth here, although it’s odd to see so many leaves in a Christmas story. But this chapel is an actual chapel. A little Christian church with a peaked roof, barely even in ruins. Did David Lowery even read the poem? Have we really become so stupid that we can only grasp the most literal meanings of words?

The whole film seems like an attempt to show how much more sexy and interesting and nuanced we are in the twenty-first century than the Gawain author was in the fourteenth, but it fails every single time. Take the exchange game. In the poem, Gawain arrives, wounded and starving, at a castle. Its lord takes him in, but proposes a deal: every evening, each of them will share with the other whatever they received that day. This is followed by a gorgeous series of alternating stanzas, in which the lord goes out hunting while his wife sits by Gawain’s bedside, begging him to fuck her. At the end of the day, the lord shares his meat with Gawain, and Gawain kisses him on the lips. The woman is very beautiful, but if he sleeps with her he’s honour-bound to have some hot, sweaty gay sex with her husband too. This is excellent and very funny. But in the A24 version, the wife doesn’t just beg; she jerks Gawain off, and afterwards we see a thin splooge of cum gracing her wrist. We’re very open now; ever since Lytton Strachey uttered the word semen in 1907 we’ve realised that we can show the stuff instead of only hinting at it.4 So, obviously, the film will have to show Gawain giving a handjob to his host, right? No such luck. Instead, he runs away.

The modern retelling is considerably more prudish than the mediaeval original. Everything here is gelded. Its Gawain has no totemic qualities; he’s not a highly-wrought image of improbable chivalry, just an everyday neurotic trapped in some bourgeois family drama. In this sense he’s more realistic than the Gawain in the original poem. But the poem managed to say something quite deft and meaningful about the human experience, precisely because it operated at a low resolution. It takes place in the bright symmetrical world that swamps half the human psyche. The film does not. Gawain’s moment of human weakness loses all meaning. In the end, it’s just a guy doing stuff.

The real crowning achievement of A24 Brain, though, is obviously Everything Everywhere All At Once: the most noxious piece of anti-Asian racism America has produced since the Chinese Exclusion Act. Here, the whole argument is laid bare. Immigrant parents aren’t American enough! Even when they try to be nice and nurturing, they say things like ‘you need to eat healthier food, you’re getting fat.’ They need to talk more about their feelings! They need to constitute themselves in the correct, twenty-first century, Western way, as bundles of traumata and neuroses, or else the whole of reality will fall apart! The richness of being is represented as a black consuming hole, an everything bagel with everything on it, devouring worlds. Spin it, play with it, have your fun in the first act, but don’t get too close. You can only retreat into emotive pap, into an A24-cum-Hallmark ending, where the family is reconciled and everyone hugs and cries.

Anyway, I watched Beau is Afraid, Ari Aster’s latest, with the full intention of being unnecessarily cruel about it here. The trailer makes the film out to be a kind of inspirational odyssey, scored with an upbeat Supertramp remix: ‘From his DARKEST FEARS comes the GREATEST ADVENTURE.’ But annoyingly, the actual film is quite a lot better. Critics are lukewarm; they think it’s overlong and self-indulgent and confusing and that the characters don’t make sense, which is usually a good sign that there’s something worth paying attention to here.

It’s essentially an extended riff on Kafka’s early short story Das Urteil, a dialogue between a son and his father. The son is recently engaged; he wants to tell his friend in St Petersburg; he wants to take care of his father. But the father is a monster. He accuses his son of trying to kill him. He calls his fiancée a whore. He insists first that the friend in St Petersburg doesn’t exist, and then that the son has betrayed his friend, and then that the father and the friend have made a secret compact. Finally, he pronounces his judgement:

So now you know what else there was in the world besides yourself. Till now you’ve known only about yourself! An innocent child, yes, that you were, truly, but still more truly have you been a devilish human being!—And therefore take note: I sentence you now to death by drowning!

Kafka’s own father was a cruel, petty tyrant, who did everything in his power to torment and belittle his son, and whose furious disapproval doomed several of his his engagements. But he did not sentence his son to death by drowning. This is the moment that takes Kafka’s story out of ordinary, grotty, partial realism. Instead of a merely bad father, we’re suddenly in the presence of the father, this frail jealous watery god who is also your father too.

There’s another monstrous parent in Beau is Afraid, but this time the monster speaks A24 Brain. Beau is not a psychological hero: he’s almost totally passive, a kind of barely-living principle of fear. He is not meant to be palpable or realistic. But the monster buries him in senseless character and motivation: a furious spiel, in therapy-speak, utterly misinterpreting every major event in the film. This monster really does love its child. It condemns him to death by drowning anyway.

I’ve spent a long time writing and thinking about therapeutic realism, the strange ways in which it snips and shears at the actual human psyche, the limp violence of being reduced to feelings and experiences, the grey flat drooling cretinism of it all. The way its products come out feeling less human than Wile E Coyote, who at least manages to express some tiny, doomed, fanatical instinct in everybody’s soul. I don’t think I’d ever really succeeded, because I’d been thinking about it too literally, which is what I’m still doing here. But now I get it. Now it all makes sense.

From the same essay: ‘It is a brazen transgression to praise an author for the psychology of his characters, and if critics and writers deserve one other for the most part, it is only because the average novelist makes use of those threadbare stereotypes which the critic can then identify and, just because he can identify them, also praise.’ He got it. In fact, you could construct a whole guide to bad characterisation out of everything Benjamin doesn’t like. Flashbacks, for instance: no prestige product can go five minutes without cramming in an obligatory slog through the character’s past. But Benjamin commends Dostoevsky for not doing this with Prince Myshkin. ‘His life before and after this episode is essentially veiled in darkness, not least in the sense that he spends the years immediately preceding it, like those following it, abroad. What necessity carries this man to Russia? His Russian existence rises out of his obscure time abroad, as the visible band of the spectrum emerges from darkness.’

Obviously First Reformed was very, very good.

This is Tolkien’s modern English translation. The original Middle English text, which I had to hack my way through at university, is somewhat þornier.

Although the Middle Ages weren’t exactly shy either. See the Anglo-Saxon riddles in the Exeter Book: ‘I saw two wonderful and weird creatures out in the open unashamedly a-coupling. If the fit worked, the proud blonde in her furbelows got what fills women.’