How to live without your phone

Forty days in the desert of the real

I bought my first smartphone in 2012. At the time I was an undergrad at the University of Leeds, halfway through a year abroad at UCLA. If you’ve never made a similar move, you can’t possibly imagine what it was like to be thrust suddenly out of the damp armpit of West Yorkshire and into the California sun. I was twenty-one years old and I had just discovered that happiness was possible. It was in California that I stopped smoking weed for good, even though it was basically legal and definitely everywhere: I knew I only had a few months until the world would spin again and dislodge me back in the land of dry stone walls, lukewarm ale, and the grey, all-enclosing gloom of three o’clock in the afternoon. I did not want to waste those months getting high and watching cartoons. I wanted to drink the desert while I still could. Plunge into the black hole nowhereness of this sprawling evil city. I started lifting weights. I did all my reading shirtless on the beach. I also started getting really into cocaine.

Another thing I did was join the Daily Bruin, UCLA’s venerable student newspaper. This was on the understanding that if I wanted to be a writer some day, I’d have to start out doing actual journalism, interviewing boring university officials or equally boring students for stories I didn’t really care about. (‘Campus Parking Fee Hike Draws Ire.’) Back then, it still wasn’t clear just how much the media had already changed. I’m not sure it’s improved, and maybe the situation would be better if you did have to put in your hours on piddling parking-fee-hike bullshit before you could blather about art or politics or whatever for the rest of your life, but I quickly worked out that this was no longer the case. Before I dropped out, though, one of the editors goggled in amazement at the phone I’d brought over from the UK, which had twelve numbered buttons and could make calls and send text messages. What was I, he asked, some kind of chimney sweep? Not that you needed a smartphone to do journalism, but everyone else had one now. So I got one too. And then afterwards, I was stuck with it. This machine was full of possibility, but I still wasn’t sure exactly what it could do. Live navigation would be good; at the time I was getting around LA by writing myself little notes with the numbers of different bus lines on them, and since the city seemed to be underserved by twelve different transport providers at once—all of which, it turned out, mostly catered to violent maniacs—I was constantly getting lost in various neighbourhoods that all looked exactly the same. What else? Well, you could download apps. So I downloaded an app called Fruit Ninja, a game in which you cut imaginary fruit in half. It was strangely compulsive. You just swipe your finger, and look, the melon slices open like magic. The world in the phone is so intuitive. It always does exactly what you want. The upshot was that I spent a portion of every single one of my remaining days in California on my own, indoors, cutting imaginary fruit in half.

I stopped playing Fruit Ninja, eventually. But for nearly fourteen years afterwards, I stared at a smartphone every single day. Five thousand days, all in all. I can’t think of anything else I’ve done with the same level of commitment. There have been days where I’ve had nothing to eat or drink and there have been nights when I didn’t sleep. But until very recently, I never once went twenty-four hours without remembering to look at my phone.

In 2012, a lot of people were very enthusiastic about the phones. Why wouldn’t they be? We’d finally been liberated from boredom. We’d abolished distance. On those late-night buses in LA, I sometimes saw women on their way to the morning shift, who’d hold up their phones and coo in Spanish to babies that might have been gurgling thousands of miles away. There are no barriers any more. Everything is everywhere. Some people thought the phones might help spark the big political shift that would finally free us all. People could organise independently, share knowledge, form communities, connect with each other across every possible social divide. The phones were showing us the social form of the future: a spontaneous, self-regulating, non-hierarchical network, gently swaddling us all in a billion strands of information and light. Or you could just marvel at how much of everything is available now. All of human culture, infinitely accessible. You can read any book. You can have any artwork you want, anywhere in the world, in the palm of your hand. Which is, of course, exactly what we ended up doing with the phones. We used them to look at art.

Maybe there are still a few of those enthusiasts out there. Scuttling under rocks or in the loam, pale and soft like hermit crabs. Creatures that aren’t complete without a bit of plastic to hide under, whose antennas still twitch greedily when they release the specs for every new iteration of the iPhone. Apple’s marketing department seems to think so; they’ve even discovered a new emotion, ‘newphoria,’ which is the sensation one of these creatures experiences when they replace their old phone with the latest model. But it’s hard to imagine them surviving long. Now, we know that newphoria is the excitement of a prey animal being hunted by a bold, fresh, thrilling new predator. Now, almost everyone accepts that the phones are bad.

This is not a new idea. But a decade ago, phones bad was still a basically aesthetic impression. It felt weird to see so many people uniformly fascinated by dark rectangles. It felt ugly to be out in public, on the train, in the park, and notice that absolutely everyone was staring silently at their phones. Maybe every technology arrives ugly. The new always comes shrouded in the sense that old ways were much better, simply by virtue of being old. So for a while, you could plausibly dismiss the people who didn’t like the phones. People have always resisted change; that’s the one thing that never changes.

It works the other way too, though. For several centuries now, people have defended new things by pointing out how uniformly people have rejected new things. But sometimes a new gadget is not actually good. Maybe radium toothpaste is not just the fast way to a winning smile. And over the last few years, we’ve seen what this particular new thing has done to the kids.

We thought we were just having fun times with devices; it turns out we were spreading nuclear waste over the entire surface of the earth. Piling up heaps of radioactive slag inside our homes. Smearing it over our faces at night. And then a generation was born into that poisoned world; we got to watch them take shape, and it became obvious how broken they are, how we had broken them. The kids can’t read. They can sound out the letters and recognise words, but they find it impossible to sit in one place and ingest a single extended linear piece of prose for more than five minutes. The kids don’t go outside. They don’t feel the sun on their skins. They spend whole summers locked in their rooms, alone, experiencing the world through five and a half inches of glass. The kids don’t fuck. They identify with various modes of sexuality based on the kind of images of themselves they’d like to maintain, but none of it has anything to do with feeling the warmth of another person’s skin on your own. Some of them want to have sex with cartoon characters. The kids are desperately unhappy. They do not like the lives we have given them. A lot of them would like to live differently. But they can’t stop looking at their phones.

It’s strange, though: even though we know the phones have poisoned everything, we still keep using the phones. All the sharpest critics of digital technology and its effects on the human psyche are also constantly looking at their own glowing rectangles. I know people who’ve written books on the subject, but I’ve no idea how they found the time, what with the staring and flicking and scrolling that seems to constitute their entire lives. Maybe this is as it should be. In the face of the vastness of this catastrophe, trying to limit your own personal screen time feels a bit weak. A copout. It’s not very systemic, is it? Not a solution, more like a refusal to actually grapple with the scale of the problem. Run to your little walled garden, stick your fingers in your ears. The phones are bad, they’re apocalyptically bad, but can you even understand the world if you’re not constantly on your phone?

I am not a Christian, but my girlfriend is. And since she’s agreed to spend eight days a year commemorating an exodus that never actually happened, and to do so by forsaking basically all carbs except potatoes and one particular variety of dry cracker, I’ve agreed to join her every year in observing Lent. Last time, she gave up her morning coffee. I don’t drink coffee, so that one was pretty easy. This year, she decided to go forty days without her phone. Her average daily screen time was one hour and twenty minutes, and she was worried that she was spending too much time looking at crap on Instagram instead of reading books. Meanwhile, I’m a persistent critic of digital technology and its social consequences. I keep on writing about how bad this stuff is, sometimes in some of the most prestigious publications in the world. Which is to say that my daily screen time was much, much more than hers.

My five-thousand-day streak of looking at a smartphone ended on the 14th of February, 2024. My new phone was a TCL Onetouch 4021, which looks like this:

The Onetouch costs £17.99 from Argos. It can make phone calls and send text messages. Beyond that its capacities are limited. It has an alarm clock but no timer. There’s a calendar, but you can’t add any of your engagements. It does have a full colour screen and even a camera on the back, but its built-in memory of 4MB is just enough for four photos, or one fourteen-second voice memo. You can insert an SD card if you want. You can also use two SIM cards at the same time, although it turned out that neither of our SIMs actually fit in the thing. We had to walk to a Vodafone shop to see if they had any nano-to-micro SIM adapters, which they did, in the back of a drawer nobody had even tried to open for most of a decade. There was some kind of procedure for selling them to us, but none of the staff were sure how it worked, so in the end they just gave them to us for free. Good luck with the drug dealing, they said.

This year, the beginning of Lent coincided with Valentine’s Day. Valentine’s is, of course, an instrument for transforming the singularity of romantic love into a predictable annual stimulus for the wood-pulp industry. But because I’m in love, I took my girlfriend out for a £200 meal at the Quality Chop House on Farringdon Road in London. (Actually, I suppose the meal was paid for by forty of my monthly subscribers. Remember that when you sign up as a paying subscriber to Numb at the Lodge, every penny goes towards hard-hitting journalism like this.) She got the leg of lamb; I got the pork collar. The pork was tender and bouncy and crowned with a ridge of gorgeous crunchy fat, but some of the best eating came from the starters and sides. The doughnuts with cod’s roe didn’t provide the usual fussy dots of food you get from fine dining restaurants, but a proper thick smear of pungent smoky taramasalata, lifted by the vinegary zip of the doughnuts. Maybe the best things we ate were the famous confit potatoes: slabs of a hundred thinly sliced layers cooked in duck fat until the insides were buttery soft and the outsides were crispy and serrated enough to cut through a loaf of bread. Anyway, I don’t really need to keep up this Jay Rayner impression, because I can show you. Out of sheer habit, I took a photo on my phone. Here it is.

Photographing my food is probably my worst habit, but I’m not alone. Every time I go out somewhere nice, I see the ritual: nothing arrives on anyone’s table without a good minute-long photoshoot. We can’t eat our food without immortalising it first. I can make excuses: I’m interested in food, I cook a lot, I’m learning, which is why it’s fine when I do it. Lies. Meanwhile, every article on the phenomenon online seems to cite the same bogus study in the Journal Of Consumer Marketing about how Instagramming your meal actually makes it taste better. I’m pretty sure it’s not that either. Over the course of my forty days without a phone, I noticed a stab of anxiety every time I ate something without being able to snap a picture first. Clearly, it wasn’t just that food looks nice; these photos were supplying some hidden need. They’re bound up with pain and fear. This neurotic tic that everyone has but no one will name, that came into being as soon as we all got our phones.

I think it has something to do with the temporally bound experience of food. Eating a really good meal might be the most enjoyable thing you can do in public, but it’s also an act of destruction. You are taking something beautiful and reducing it to nothing. The enjoyment lasts for only a few short minutes; when it’s done it doesn’t leave a single trace. Not even memories, not really. You can remember things you’ve done or places you’ve been, but you can never really conjure the taste of a meal you ate months or years ago. It’s all locked away in a particular moment. A vanishing, mayfly version of yourself that evaporates almost as soon as it appears. This fixation in time does mean that smelling or tasting something familiar can catapult you into a Proustian re-experience of the past, in a way that sights or sounds can’t. (I recently caught a whiff of the same brand of cheap American air freshener I’d used in LA, and suddenly everything collapsed into place: the white-hot sun, the sea without swimmers, the demonic sprawl; for an instant I was twenty-one again and horny and the world was about to be mine.) But fundamentally, when you pay £200 for a fancy meal, all you’re shelling out for is tomorrow’s turds.

Until yesterday, people had to accept that sensory pleasures carry a gloomy intimation of death. Keats understood this perfectly:

She dwells with Beauty—Beauty that must die;

And Joy, whose hand is ever at his lips

Bidding adieu; and aching Pleasure nigh,

Turning to poison while the bee-mouth sips:

Ay, in the very temple of Delight

Veil’d Melancholy has her sovran shrine...But we don’t have to understand this if we don’t want to, not any more. Before the advent of the smartphone, it was impossible for anyone to record every single meal they ate; now, it’s the norm. I take photos of my food to make this transitory moment last forever. A record of what has been destroyed; a monument. Somewhere inside my phone, the passage of time has been stalled. But I never look at these photos. They have no relation to the visual functions of pre-phone photography; their purpose is simply to exist. Every second, millions of people are taking millions of these useless photos of food, photos that don’t represent their object but help you ignore something else. It could be worse. At least with food you do still eat the thing afterwards. Next time you go to a concert, though—or a sports game, or whatever—notice what everyone else is doing. They don’t want this moment to vanish, so they film it on their phones, even though they know that they’ll never watch the footage again. They’re watching it this time, though. They’re watching the entire performance through their screens.

I don't want to give the impression that giving up my smartphone radically transformed my life. There were some weird new sensations sometimes, and others I’d almost forgotten, but what was most striking was how little actually changed. I told my friends that it was better to get me on SMS instead of WhatsApp, and they all WhatsApped me anyway. This meant that instead of ambiently communicating with people all day long on my phone, I was intensively communicating with them for about thirty minutes on my laptop. The practical difference, in terms of making plans and so on, was about nil. Things are rarely all that urgent.

Not having a smartphone is entirely practical. You do not need it. This machine barely does anything at all.

There is one function that’s genuinely useful. Having a live, searchable GPS has some very real benefits; before I bought my first smartphone, I could imagine how it would improve my life. (Are people who’ve never had the pleasue excited by the prospect of scrolling through TikToks?) Last year, I could arrive in the middle of some smogbound provincial city in Henan province, China, and instantly find my way around. That was nice. The prospect of suddenly losing that power came with some anxiety. My girlfriend had a dream in which her train broke down and she was stranded in the middle of nowhere. She couldn’t even get a cab, because there weren’t any taxi companies saved in her stupid new phone. All she had was an address, which was carved in a stick of butter. As she tried to show it to people, it slowly melted in her hands.

In the waking world, though, nothing like this ever happened to her. Instead, it happened to me. Shortly after getting my Onetouch, I had to walk down to the Japan Centre near Piccadilly Circus to stock up on my kombu and umeboshi and other froufrou bullshit, and it was only once I was at the curly end of Regent’s Street that I realised I didn’t actually know where the Japan Centre was. Somewhere around here—but where? I confidently strode down one wrong street after another, doubled back, failed again. Eventually I found myself in the tangle of alleys around St James’s and realised to my horror that I was—in the middle of my own city, in the tourist heart of London, in a place with more world-famous landmarks per square kilometre than anywhere else on the planet—lost. I couldn’t remember the last time I’d been lost. People don’t get lost any more. It’s one of those charming old experiences, like looking something up in a big encyclopaedia, or dying of polio, that’s been made obsolete by the forward march of technology. Not so long ago, hack comedians used to talk about the small rituals you have to perform when you realise you’ve walked the wrong way. You can’t just turn around; that’s maniac behaviour. You have to pat your pockets or make an exasperated tutting sound; that way people will know that you’re turning around because you’ve forgotten something, which is a far less embarrassing mental lapse than managing to get yourself lost. I don’t think anyone does that any more, because we’ve stopped walking the wrong way. We are all always on the most efficient possible path between two points.

Weirdly, I didn’t mind being utterly lost less than three miles from my own front door. It was very slightly thrilling. With the phone, navigating the city becomes a kind of augmented reality game, in which you move your legs and avoid various obstacles to direct a blue marble along a dotted line onscreen. Now all my directions had to come from the city itself. Did this turning look like the right one? Did it feel like it might take me home? Being lost means paying intense attention to the texture, the Erfahrung, of where you are, while having only the haziest sense of its location relative to other places. Navigating via phone is the opposite: you know exactly where you are, but it’s not really anywhere in particular. You sink into a kind of abstract mental tunnel until you reach where you’re going. A new, inverted form of being lost.

It is possible to know your surroundings well enough that you don’t get lost. This is what most people have done for most of human history. Horse nomads can traverse a hundred miles of featureless steppe without ever wondering where the fuck they actually are. New Guinean highlanders can effortlessly find a single fruit tree in the dense and trackless woods. London cabbies famously memorise the layout of the entire city. Once, this made them extremely reliable; now, all that specialised local knowledge gets you to the exact same place as an Uber-driving immigrant. But Uber drivers have described entering a strange trancelike state while at work. You drive all night in a kind of dream; afterwards you can’t even remember where you’ve been, who you picked up, where you dropped them off. You just turn left when the voice tells you to. Human consciousness as a brief, lossy interface between the navigation app and the steering wheel.

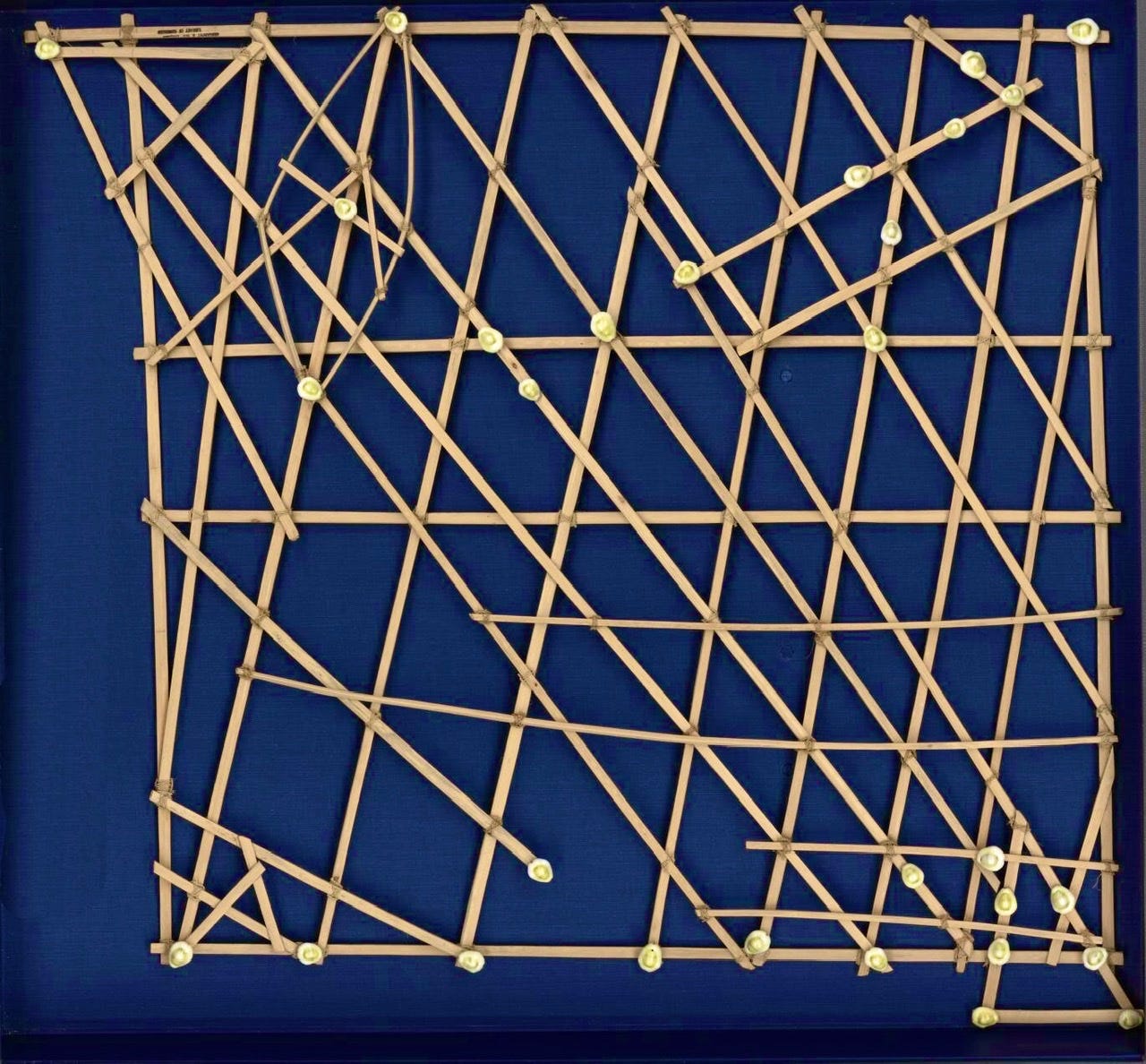

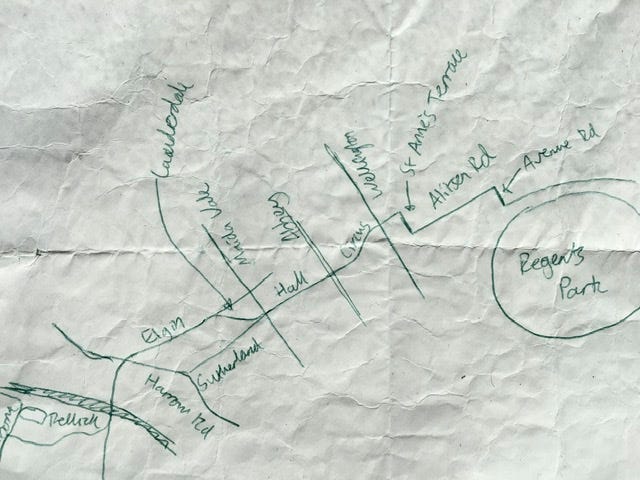

There are ways of uniting abstract relational geography with the concrete experience of being in a particular place. Song lines, ley lines, mystical structures that turn the physical landscape into a piece of narrative. But the simplest way of doing this is to make a map. I think the most beautiful maps ever made are the stick charts made by the seafaring aristocracy of the Marshall Islands, which don’t represent solid objects, since there are no solid objects in the endless sea, but track the zones of ocean swells. These swells are produced by the position of landmasses and the churning of transoceanic weather systems, but ultimately they’re governed by the action of the Earth’s gravity on the boundary between sea and sky. Stick charts map the entire world, from the atmosphere down to the planetary core. They look like what they are: abstract, fantastically intricate computers made from cowrie shells and coconut fronds, interoperable with the universe in general. (There’s one at the top of this post.) My own maps were much less ambitious. I must have made dozens of them. Here’s one:

I’m not sure why, but everyone who saw these maps found them hilarious. As if they hadn’t used them too. We’re not so young. We all printed them off MapQuest, once upon a time. We scribbled them on the backs of receipts. We went on holiday to foreign cities with just a few lines on paper to guide us. We managed. It is actually completely possible to get around without a phone.

There were, admittedly, a few incidents in which I had to break my fast and briefly turn my phone back on. Most of these involved two-factor authentication, and I’m pretty sure they could have been avoided if I’d planned ahead a bit better. I turned the phone on to go for a run, but I could easy replace it with a FitBit and an antique iPod. The other incidents were all down to something called Gusto, a payroll service that half the publications I write for seem to have adopted at the same time. I quite badly needed the money they owed me, but to get it I had to sign up for Gusto on my phone, upload my ID, and then perform a bunch of humiliating facial contortions for my front-facing camera so the biometric software could be certain that I was actually myself, and not someone deviously impersonating a freelance writer to get their greedy hands on the vast, vast riches we accrue. I did this several times, and each attempt ended with an error message telling me that my passport and biometric information were incorrect and didn’t match the data in their system. Apparently my face was wrong. But if they already had all my data in their system, why was I going through this whole stupid process in the first place? In the end I just emailed my various editors asking if they could send me the money without involving Gusto at all. It turned out they could. That was all it took.

Obviously my job gives me a lot more latitude than most people’s, but I still suspect that if you think you need your phone for work, you’re probably wrong. You do not need to be writing emails on the move. If you have to write emails, do it when you get home. When I was a child, I had a plastic folder full of Wikipedia articles I’d printed out to read on the bus. This is also possible.1 Technologically, there’s nothing your phone can do that an ordinary computer can’t. These machines haven’t changed the world because they have any very notable capabilities. They just have the right shape for latching onto the soft part underneath your mind.

What everyone really wanted to know about giving up my phone was whether it had miraculously increased my attention span, and whether I was getting any more reading done. To be honest, I’m not sure. In the six weeks of Lent I read ten books, which is decent going but not really exceptional, even if some of them were quite long.2 But reading did feel easier. Usually, whenever I sit down with anything more demanding than your average Sunday Times bestseller, I instantly start hearing the voice of a scratchy little demon, scratching away at the inside of my skull. Look at your phone, it says. Stop reading and look at your phone. Look at your phone this instant. Something might have happened on your phone. The book will stay the same forever but there might be something new on your phone. You might have notifications. You might have some of those red circles you crave so much. You can just put the book down for a moment. One quick moment to look at your phone. Don’t you know who I am? My name is Astaroth and in the Ars Goetica or Lesser Key of Solomon I am a mighty, strong Duke of Hell commanding forty demonic legions. I can show you fulfilment beyond your knowing if you choose to follow me, but first you must LOOK AT YOUR PHONE.

Sometimes I managed to resist Astaroth. But he was always there, and if I gave in to his temptations for even a moment, suddenly it was already dark, the day was gone, and I had absolutely no memory of what I’d been scrolling through for the last three hours. I suppose I was looking at whatever I wanted to look at in that particular moment. Huge complex machines exist purely to show me more of the kind of things I like. Strange how all this fulfilment never seems to leave you feeling good. Strange how indulging all your idlest urges feels like you’ve mortgaged a portion of your life to Hell. Anyway, I expected Astaroth to stick around for a while after I got rid of the phone, like a nicotine craving. But he didn’t. As soon as checking my phone was no longer an option, the desire to do so simply vanished.

Or it did, as long as I was doing something else. I could read. But in every idle instant, Astaroth reigned. Every time I met someone at a pub, there’d be a nightmare moment when my friend’s round came and he went up to the bar, leaving me alone at a table with forty demonic legions all commanding me to look at the phone I didn’t have. The horror of simply existing, sitting alone with nothing to look at, nothing to do with my hands, no bright lights to briefly flood my brain. Once, in desperation, I started clicking through the UK Radio Equipment Regulations compliance statement buried in an obscure sub-menu on my Onetouch, until my friend returned with my pint. That same itch would come whenever I was waiting for someone outside a venue or a Tube station, or when I found myself on public transport without a book or a newspaper, or when I was watching a film with my girlfriend and she paused to use the loo. Instantly, fingers started twitching to go on my phone. This wasn’t simple boredom; it had all the restless tachycardia of an anxiety. It is awful to exist in these in-between moments. When you’re doing nothing except existing, when your only available object is your own existence, when you’re facing the full demonic inconceivability of being here, in the world, thrown into awareness of your own being for a reason you will never know, or possibly no reason at all. Nobody wants to think about that shit. So you look at your phone.

I’m told that smoking has declined basically in tandem with the rise of the smartphone. This makes sense. They’re both something to do with your hands in the empty moments, before or afterwards, when you’re waiting for something else to happen. Both of them will also kill you.

Once, I was in Chicago for an afternoon with nothing to do, so I decided to be a tourist and go up the viewing gallery at the top of one of the skyscrapers. I shared a lift with a dad and his three preteen boys, who spent the ride punching each other in the ribs. When the doors opened, the vast flat expanse of the American midwest was laid out in front of us, falling into the equally vast flatness of Lake Michigan. We were almost level with the clouds, and as the setting sun burst through them the fingers of God gently stroked this world he had made. But the observation deck also had some big touchscreen displays that let you zoom in on the view to identify the various landmarks. Instantly, the boys pelted for the screen and started tapping and swiping at the image of what was right outside the windows. Their poor dad was left wailing. He had brought his sons here to show them something beautiful, and they couldn’t even be bothered to give it a perfunctory glance. ‘It’s there!’ he kept saying. ‘It’s right there!’

To live is to live in the world. What we do on the screens is something else.

After a while without my phone, I started to really notice how much everyone else was staring at theirs. On public transport in particular. Every adult is sitting there, pushing around coloured squares and popping coloured bubbles. They are playing with toys for babies. Now look at their faces. These people are not being entertained. They’re not having fun. They are turning their brains off while they wait.

Not using a phone taught me what a phone is really for. It’s not for communicating with other people, getting directions, reading articles, looking at pictures, shopping for products, or playing games. A phone is a device for muting the anxieties proper to being alive. This is what all its functions and features ultimately achieve: cameras deliver you from time, GPS abstracts you out of space, and an all-consuming screen that keeps you a constant safe distance from yourself. If there’s something you’re worried or upset about, you can simply hide behind your phone and it will all go away. One third of adults say they’re on their phones almost constantly. Their entire waking lives are spent filling time, plastering over the gaps, burning up one day after another, waiting for something to happen, and it never does.

I’m not trying to dismiss the anxieties proper to being alive. These are serious anxieties, and I’m not sure they have any easy solution. Maybe the phone is a perfectly workable answer: to keep deferring the problem, one day to the next, until eventually it goes away for other reasons. Spending forty days without my phone did not make me magically happier. I wasn’t awed by the sunrise every morning. I didn’t suddenly find that all my relationships were so much deeper and richer. I did find myself ambiently uncomfortable in situations that had previously been helpfully smoothed over by a glowing screen. I got bored. I got lost. But I did also get more reading done, and my days did feel like they had more things in them. Since I’ve started using the phone again, my weekly screen time’s down to a fraction of where it was before. It’s weirdly hard to go back. The phone can have my attention, but it’s incapable of maintaining my interest. Perfect things are not that interesting, and the phone is smooth and flat and flawless, while the alternative has some very prominent design problems extending to basically every area. Reality is not intuitive or instantly responsive to all my fleeting whims. It does not immediately yield whatever I want. Most of the time it seems to barely recognise my existence. This might be better for you in the long run; on an immediate level it’s very frustrating. But for better or worse we have been condemned to live. All we have is what’s right here; the only thing that ever is or ever will be here.

Right now, you are—statistically speaking—reading this on a smartphone. It’s not really in my best interests to say this, but you should probably stop. If you want to read something, read it on paper. Print it out! Take it to the park and read it there! And if it isn’t worth the effort, then why are you reading it at all?

If you’re interested: I read Ovid’s Metamorphoses, in David Raeburn’s translation for Penguin Classics, which I found a bit disappointing; it was very readable, but the verse just felt like prose with line breaks, and in trying to avoid the stuffiness of academic Latin it ended up being a little plain. But I also read Virgil’s Georgics in LP Wilkinson’s translation, also for Penguin Classics, and it’s gorgeous. Listen:

Never did lightnings flash more frequently From a clear sky, never so often blazed Dire comets. So it was that a second time Philippi saw the clash of Roman arms With Roman arms, nor did it irk the gods That twice Emathis and broad Haemus’ plains Should batten on our blood. Surely a time will come when in those regions The farmer heaving the soil with his curved plough Will come on spears all eaten up with rust Or strike with his heavy hoe on hollow helmets And gape at the huge bones in the upturned graves.

I read The Green Man by Kingsley Amis, which has some moments but isn’t really his best. I read EE Evans-Pritchard’s Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic Among the Azande, which I intend to write about a lot more later. I’d already come across the title essay and ‘Notes on Camp,’ but I read the rest of Sontag’s Against Interpretation. (Incredible that the role of the serious American intellectual was once to inform her readers what was coming out of Europe. Now there’s nothing coming out of Europe, and the type of American who used to preen over Godard and Gide now just congratulates themselves for watching prestige TV.) Because Sontag kept dropping his name, I finally read Man’s Fate by André Malraux, which did make me consider how much more afraid of death I am now I’ve cooled on the prospects for Communist revolution. Although after that, because I’d read a review in the LRB and it seemed interesting, I read The Siege of Loyalty House: A New History of the English Civil War by Jessie Childs, which was very human and evocative but did leave me wishing for a bunch of tables showing grain prices and real wages over the course of the war, so maybe I am still a good Marxist after all. A reader told me that my piece on truly foreign languages reminded him of China Miéville’s Embassytown, so I reread it to discover that yes, my thing really is identical, although that’s probably just because we’re both adapting the same Walter Benjamin essay. I read Palestine+100, a collection of science fiction stories by Palestinians, mostly in the diaspora, of which many were interesting, although only one, ‘The Curse of the Mud Ball Kid’ by Mazen Maarouf, was actually meaningfully good. Finally, it occurred to me that I’d never actually read The Brothers Karamazov; the person who read it was some dumb kid who happened to share my name. So I read it again. Dostoevsky is a great writer, but maybe not a good one. His books sag with blather: page after page of drunks rambling, matrons shrieking, people turning purple. And then he’ll very lightly season this overwrought, hysterical Victorian nonsense with some of the most devastating moral observations ever put to the page. A friend told me that whenever she tried reading him she always felt like she’d got the wrong translation, but maybe she actually just fucking hated Dostoevsky. I don’t know if I agree. But I do understand why.